People are fascinated by the end of the world.

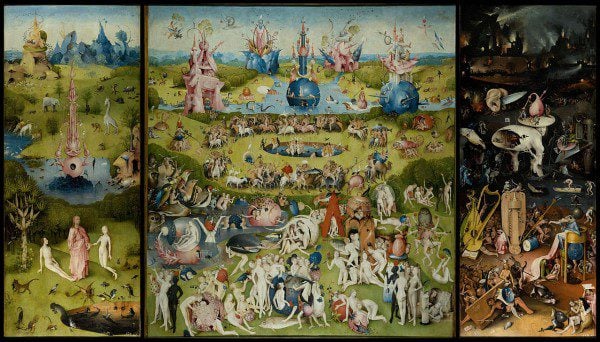

Global annihilation. Widespread famine. Fire and floods. “The Battle of Armageddon.” Angels and demons battling it out. Good versus evil. The Antichrist. You name it.

People are fascinated with these doomsday scenarios. But why? That’s one of the questions Morgan Freeman asks in the second episode of The Story of God. The episode is devoted to the apocalypse.

Maybe we’re intrigued for the same reason we look at car crashes. We’re mesmerized by the dramatic, by big action, by life-and-death scenarios. It’s a chance to face into our deepest fears about the fragility of the world and the possibility of a violent end to it all.

Fundamentalist religion knows how to capitalize on those inner fears, those deep anxieties.

I remember, as a young teen, being shown A Thief in the Night at youth group one night. This was the 1972 film about the “rapture” (the 70s iteration of the more recent “Left Behind” films–each generation needs

its own!). The story is told through the eyes of Patty, whose husband is snatched up in the rapture (a fundamentalist Christian apocalyptic idea, which enjoys no actual support in the Bible). I’ll never forget that electric razor buzzing on the kitchen sink, signifying the sudden departure of the born-again husband (and, apparently, a marital union now forever separated by the return of Jesus?).

The point? Be sure you’re not left behind, too! The tribulation is coming. Immeasurable suffering, turmoil, war. Marks of the beast, and all that.

Apocalyptic ideas have a long history in both Judaism and Christianity (and Islam, too, though I’m much less familiar with that history).

James Vanderkam offers a simple, short definition of apocalyptic literature in the Bible, both Hebrew Bible and the New Testament: “Divine disclosures of what is destined to take place.”

In apocalyptic literature, God-usually through some kind of angelic messenger or prophetic visionary-offers a window into the future. And the picture is usually high on drama, violence, and even cosmic transformations. But these pictures are highly charged with imagery, symbolism, and allusion. It’s not usually meant to be taken literally–as if all things things are going to happen as just described, in a straightforward way.

We’re not supposed to be watching Fox News and aligning contemporary events with happenings in the the letter of Revelation, for example. It’s probably the case that well over 90% of the events described in Revelation (and in all of the apocalyptic literature in the Bible) have already occurred–thousands of years ago.

But is there something apocalyptic that is yet to occur? Should we be anticipating a violent, virulent, dramatic end to this age, to this history, as an eruption of a new age?

Christian theologian Jürgen Moltmann, no fundamentalist himself, helps us see why apocalyptic has always had a place in religion. In The Coming of God, he writes,

The reason for the apocalyptic hope in the downfall of the world is pure faith in God’s faithfulness. It is not optimism. God will remain faithful to his creative resolve even if the world he has created founders on its own wickedness. God’s will for life is greater than his will for judgment…

Apocalyptic expectation is not stolid resignation to fate. It raises up those who are cast down. True apocalyptic teaches people to ‘lift up their heads’, and to be open for God’s new beginning in the breakdown of this world system which they perceive.