Good Friday reflections on the cross usually focus on the significance of Christ’s death for humans.

Christ died for you and for me. Or even, Christ died for the world–with the world taken in an abstract sense or as a cipher for all human beings.

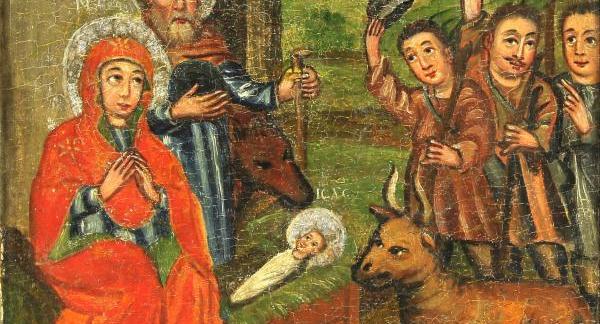

But why shouldn’t the “world” include all living creatures? Why shouldn’t it include non-human animals? Your dog, your cat, your parrot? The chipmunk tunneling under your house?

In short, if human beings are in need of Christ’s atonement, so is all of creation. All creation stands in need of healing, of redemption, of reconciliation.

Perhaps the apostle Paul implies this in Romans:

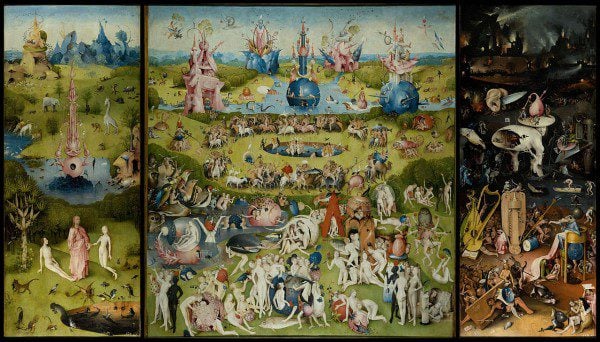

I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us. For the creation waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God.

We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time.

Doesn’t “creation” include all of life, every living thing–every species, including the 98% which are now extinct? The reconciliation of the cosmos in Christ is a total reconciliation.

In Christ and Evolution: Wonder and Wisdom, Celia Deane-Drummond includes an interesting discussion of the application of the meaning of the atonement for non-human animals.

If we take evolution seriously then we have to take death and suffering seriously in our theology. Furthermore, we should recognize that the usual qualitative distinction drawn between human beings and all other animal life is mainly unfounded. We can posit quantitative difference (sliding scale differences) between some capabilities of human beings (intelligence, moral reasoning, etc.), but that doesn’t that human beings possess those things while other animals do not.

Deane-Drummond acknowledges that to speak of “morality” in non-human animals is complicated and controversial. She offers the distinction of a “three-dimensional” morality in humans and only a “two-dimensional” morality in other animals, insofar as “they are unable to anticipate harms and goods to the same extent as humans” (166).

Nonetheless, her point is intriguing: all animals–not just humans–stand equally in need of the liberation of creation, of God’s transforming and redeeming grace.

She doesn’t advocate a traditional penal substitutionary theory of atonement, but rather something more like a redemptive and transformational atonement, one in which the problem addressed by the cross isn’t sin against a holy God, but suffering, death, and evil in need of healing. Christ enters nature to heal it from within and the cross represents Christ sharing in the suffering of the world, but for the purpose of healing it in God’s love.

In this sense, cross and resurrection go hand in hand.

I love Moltmann’s suggestion that all living creatures will be included in the new creation. All will be resurrected to new life in God.

In The Coming of God, he writes,

The eschatological field of human hopes and fears, longings and desires, has always been a favorite playground for egocentricism and anthropocentricism, and for the exclusion of anything strange and different. But true hope must be universal, because its healing future embraces every individual and the whole universe. If we were to surrender hope for as much as one single creature, for us God would not be God.

So to the question: Did Christ die for non-human animals, too? I answer a hopeful “Yes!”