On June 27th, 1844, Mormon Church founder Joseph Smith, Jr. was assassinated. He was, at the time, running for the presidency of the United States. LDS missionaries, unaware of his death, carried his platform for weeks afterwards as part of their proselytizing efforts.

The winner of the 1844 election was James Polk, a slaveholder who made gains in territory but gave a de facto nod to slavery. He was succeeded by yet another slave holder—Zachary Taylor, who survived only part of his term and was replaced by Millard Fillmore, usually considered one of the nation’s ten worst presidents. It was under Fillmore that the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, making it possible to recapture runaway slaves regardless of where they were, or to claim that a black person anywhere was an escaped slave.

That year, 1850, was the very year which Joseph Smith’s platform had set as a deadline for the abolition of slavery: “Petition. . .ye goodly inhabitants of the slave States, your legislators to abolish slavery by the year 1850. . .”

Fillmore supported the California Compromise, in which California entered the union as a free state, with New Mexico and Utah free to choose by popular sovereignty whether they would be slave or free. Since Fillmore had supported Utah’s request for territorial status and Brigham Young as governor, Young named the first capital Fillmore. In 1852, as governor, Brigham Young delivered his most quoted and controversial speech to the territorial legislature: “An Act in Relation to Service.” In it, he indicated that Utah would accept slavery. To the same body, Young declared that the “seed of Cain” had no right to the priesthood. Thus, the priesthood restriction officially began.

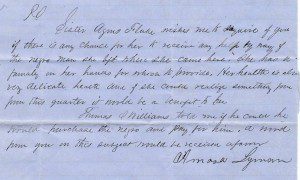

Certainly, given Joseph Smith’s platform (which Young himself had distributed), it is surprising that the Mormon settlement tolerated slavery—in fact supported it. This support is born out in several documents, including a letter from pioneer Amassa Lyman asking that Brigham Young sell one of the three “colored servants” (Green Flake) who had labored in the vanguard pioneer company. Lyman had, in fact, arranged for a buyer. His letter said: “Sister Agnes Flake wishes me to inquire of you if there is any chance for to receive any help by way of the negro man she left when she came here [San Bernardino, California]. She has a family on her hands for which to provide. Her health is also very delicate and if she could realize something from this quarter it would be a benefit to her. Thomas I. Williams told me if he could, he would purchase the negro and pay for him. A word from you on this subject would be received a favor.” Young’s answer was vague, and the sale never took place.

It’s tempting to imagine an alternate reality in which Joseph Smith did not die on June 27, 1844, but became the president. (Utterly implausible, yes, but still a good fantasy.) Granted, he would have faced the same intransigence from the Southern states as Lincoln found in 1860. Joseph Smith’s prescient words echo somewhere in time’s chambers beneath Lincoln’s more famous ones from his first inauguration:

It’s tempting to imagine an alternate reality in which Joseph Smith did not die on June 27, 1844, but became the president. (Utterly implausible, yes, but still a good fantasy.) Granted, he would have faced the same intransigence from the Southern states as Lincoln found in 1860. Joseph Smith’s prescient words echo somewhere in time’s chambers beneath Lincoln’s more famous ones from his first inauguration:

One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. . . We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Even more strongly, Joseph’s words resonate with those of Martin Luther King, Jr. Joseph Smith, as Dr. King would do 119 years later, quoted the Declaration of Independence:

My cogitations, like Daniel’s, have for a long time troubled me, when I viewed the condition of men throughout the world, and more especially in this boasted realm, where the Declaration of Independence “holds these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” but at the same time some two or three millions of people are held as slaves for life, because the spirit in them is covered with a darker skin than ours. . .

Dr. King’s most famous speech, delivered in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial, states:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

He demanded that old promises be kept, that the nation’s debt to its citizens of color be honored and no longer stamped with “insufficient funds.”

Today, in 2013, we still must acknowledge that Dr. King’s dream has not been fulfilled as fully as he would have hoped. Again, we can look at Joseph Smith’s words and wish that his ideals in this particular issue had been followed:

The wisdom which ought to characterize the freest, wisest, and most noble nation of the nineteenth century, should, like the sun in his meridian splendor, warm every object beneath its rays; and the main efforts of her officers, who are nothing more nor less than the servants of the people, ought to be directed to ameliorate the condition of all, black or white, bond or free; for the best of books says, “God hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.

Sadly, when Dr. King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, the church which Joseph Smith founded was restricting its most important privileges from any of African lineage, and many LDS leaders considered King a Communist conspirator or a puppet, not a prophet in his own way.

Now the LDS church does not discriminate against blacks, though some of the past racist teachings still linger—a challenge the leaders are slowly addressing. Its February 2012 statement declared, “We condemn racism, including any and all past racism by individuals both inside and outside the Church.”

I ask my readers to ponder Joseph Smith’s words that we are all directed to “ameliorate the condition of all, black or white, bond or free.” This implies not only that we address poverty but also profiling; not only incarceration but also education. May we recognize, as Dr. King did in his letter from Birmingham Jail, that “a threat to justice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Remember too that Joseph Smith grew in his views—which should give us all hope in our individual and national ability to evolve. Earlier in his life, Joseph, like most of the 19th century, believed in the “curse of Cain.” But by the year of his death, he proclaimed through tracts still being distributed after he was cold in his grave:

Our common country presents to all men the same advantages, the facilities, the same prospects, the same honors, and the same rewards; and without hypocrisy, the Constitution, when it says, “We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America,” meant just what it said without reference to color or condition, ad infinitum.

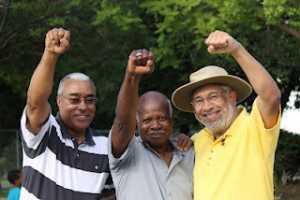

(The picture at the top of the post features black Mormons Don Harwell, Eugene Orr, and Darius Gray. Joseph Smith’s entire platform can be found at www.blacklds.org/platform. )