In 1979, I was living with my first husband in Royal Oak, Michigan. I was expecting a child, a girl, and I loved the bigness of my body.

I see my daughter now from an entirely different perspective, of course. I see her down the years as my naked newborn; my smiling 2-month-old with hair like wispy dandelion seeds; my three-year-old whose family was breaking up and who didn’t want to live so far from her daddy; my four-year-old who wore a white-tiered formal when I married Bruce Young; my twelve-year-old, who wept with me when my best friend, and her best friend’s mother (the same person), died in a car crash; my sixteen-year-old, who moved easily from graceful gymnastics to acrobatic diving; my nineteen-year-old, who became a bride even though she had sworn to not marry young; my twenty-one-year-old, who decided not to have children for another five years, and then announced a week later that she was pregnant; my twenty-two-year-old, who held her firstborn daughter in her arms, just as I had held mine; my twenty-five-year-old, who brought me to tears as she sang at her vocal performance recital; my thirty-three-year old, mother of three, who sang a duet of “Silent Night” with me to my dying father last month. Dad told me over and over how deeply it moved him–hearing our voices, mother and daughter, in harmony.

My daughter was invisible to me in 1979, a seed in my womb.

That same year, at a Bloomfield Hills stake conference, George Romney spoke about blindness. He said that when a person blind from birth receives sight, it is not a pleasant thing. They have known another kind of sight–through touch. They have not yet learned to interpret the bombardment of light and color which come with sudden sight. Sometimes, they shut their eyes to better “see” an apple, so that they can feel its form before letting the light in. They had to learn to interpret or translate light and color into something they could recognize and integrate into their understanding of form.

My youngest son would make more consequential choices than Kaila did–consequential in different ways. He would be tempted, at age fourteen, into drugs and alcohol, and would find himself addicted a few years later. The time came when he and I realized that there were too many triggers in Provo, and he needed to move in order to recover. He moved to Indiana, where Kaila was (is) pursuing her MA in the Jackman School of Music.

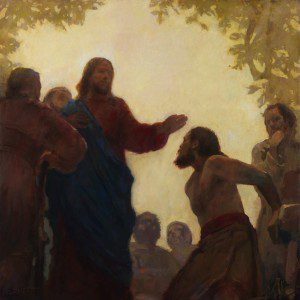

On July 30, I left Provo with my friend, Robinlee Schuler, beginning a 5,000-mile road trip to raise money for the film I’m doing (Heart of Africa). Two days later, my son moved to Indiana. Towards the end of our long trip, Robinlee and I went to Texas, where I got to help organize the Arlington Genesis Group. We stayed with Cris and Janae Baird–which stay included miracles of its own. As we were preparing to leave, Cris invited me into his office and thanked me for helping with Genesis. He gave me a priceless gift: an art print signed by the artist, J. Kirk Richards, of Jesus healing a blind man. Kirk painted it from the blind man’s perspective, so images are just beginning to come into clarity. Faces are indistinct, but the blind man’s sight has been restored, and now he will learn to see clearly and to discern.

From Texas, we went to Indiana, and I saw my son.

His metamorphosis had been lovely but hard from his birth, and he hadn’t usually recognized his own intelligence. I had once slipped into a deep depression castigating myself for not following undefined “other” paths in my raising of him, or for saying things I should not have said. But I had done a few things right, and we retain a loving bond. I did know that my unhappiness with myself made things even harder for my son. He told me, and told others, how much he loved seeing me happy–which I wrote about elusively here.

He was having nightmares. He slept in a basement room, and in the dark felt that there were evil spirits around him. “Mom,” he said, “I feel like I’m being haunted by my sins.”

I looked at the art print Cris had given me. I loved it. And I knew it belonged to my son. That it had been given to me so that I could give it to him.

I took it down to his room. I said, “A man in Texas gave me this art. I love it, and I want it. I know exactly where it will go. But, if you want it, I’ll leave it here. You have to want it, though.”

He looked at it for a long moment. “I want it,” he said.

I put it on his mantle. Robinlee and I returned to Provo.

My son has said that the best thing about addiction recovery is that you start to FEEL again. And the worst thing about addiction recovery is that you start to FEEL again.

I, miles away, continue doing my temple work, wherein I bless women’s bodies in particular ways, and do so with an understanding they themselves might not yet have. I bless their eyes. I bless their noses. (Does it seem strange to bless someone’s nose? Not to me. As my father has declined, his sense of smell has left. I brought him a gardenia one day and he sniffed it. “I can’t smell it,” he said. Oh, that his nose could smell and remember the smells that came to him throughout his life–the putrid and the magnificent; every meal his mother cooked or ordered (Arnoldi’s ravioli, Santa Barbara), every spice cake his wife made, every cinnamon-speckled bowl of rice pudding he ate during his mission in Finland; ever bowl of Borscht he ate in the Baltics; every sweet and sour sauce he tested in China; every gardenia or lily he knew.)

I told Cris how much I loved the painting he gave me, and explained that I had to give it to my son. Three weeks later, Kirk Richards came to my home with a gift from the Bairds. It was a large, framed and signed version of the painting that still sits on my son’s mantle.

The painting became the focal point for another metamorphosis in our home. I had decided to turn my son’s bedroom into a dining room, and now I knew just how we would choose the colors. Every shade would come from that painting.

The bedroom looked like this, but with lots of Bob Marley posters up:

My daughter, a gifted photographer/singer/thinker, was my designer, and her boyfriend was the destroyer/builder (for many things must be destroyed before they can be re-fashioned). I chose the bowl of glass globes for the centerpiece–several of them fishing net floats which we found on the beach in Hawaii. They had come all the way from Japan. One of them retains a bit of the Pacific ocean, somehow sealed inside it. The bowl includes glittering representations of fruit, the sort a blind person would “see feelingly.”

This is the room where we will feast with guests, and speak of good things.

I have some hesitation in publishing this, because I am telling a story which is not mine, and which is yet unfinished. I love this quote from Adam Miller’s Letters to a Young Mormon:

God’s work in your life is bigger than the story you’d like that life to tell. His life is bigger than your plans, goals, or fears. To save your life, you’ll have to lay down your stories and, minute by minute, day by day, give your life back to Him. Preferring your stories to His life is sin. Sin is endemic to the story you’re always telling yourself about yourself.

I am describing a long journey in a story much bigger than its personal components. This story happens to include me and my son and my daughter. When the story was about me, it told of a woman grieving for her blindness, for not having seen signs which would have warned her of danger. When it was about my son, it told of another kind of blindness, for he (as did the young man in “Hymn of the Pearl“) fell in with strangers and forgot that he was a son of Heavenly parents. (Yes, it’s plural in that work.)

But it is a greater story, an archetypal story. It includes Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Joseph and his brothers, the Prodigal son, the Good Samaritan. It extends into the past and goes far, far beyond anything I can communicate here en medius res. It goes beyond where I can see, and includes redemptions, relations, and restorations I have not yet imagined and will never know completely (for versions of this story are happening all over the world). I write here only of seeds and of light.