This reflection is a follow up to James Ford’s post a little while back, Jiufeng Does Not Approve: A Brief Meditation.

This reflection is a follow up to James Ford’s post a little while back, Jiufeng Does Not Approve: A Brief Meditation.

I’ve been chewing on this old case for twenty years or so – an important pointer in my ongoing search for what Dogen calls the wondrous method of practice-enlightenment (aka, shikantaza).

Katagiri Roshi would often say that there are only a few people who really know this wondrous method. I took that to heart and launched a pilgrimage that has been dragging on for thirty-five years.

The koan work that I’ve been doing, fyi, is also in service of this inquiry – what is the heart of shikantaza?

Here’s the koan.

Book of Serenity, Case 96:

Jiufeng Daoqian served Shishuang Qingzhu as his attendant. When the master died, the assembly elected the head monk as the new abbot. Jiufeng was unsure of the new master’s realization. He declared “I will test him, and if he understands what our late master understood, then I will continue as his attendant.”

The two men met. Jiufeng said, “our late teacher said, ‘You should extinguish all delusive thoughts. You should let consciousness expire. You should let your one awareness continue for ten thousand years. You should let your awareness become like winter ashes, or a withered tree. You should let your consciousness become like one strip of pure white silk.’ So, tell me, what matter was he intending to clarify with these words?”

The head monk said “Our late master intended to clarify the matter of absolute emptiness.”

Jiufeng replied, “If that is your understanding, you have failed to achieve the insight of our late master.”

The head monk was taken aback. He said, “Pass me that incense.” When Jiufeng did, the head monk lit it, saying “If I didn’t understand him, I would not be able to die as the incense smoke rises.” And with these words, he assumed the zazen posture and died.

Jiufeng reached over and gently caressed the late head monk’s shoulder, saying, “Even though you can die sitting or standing, you have not dreamt our late master’s teaching.”

Shishuang (807-88) was a successor to Daowu – the guy who wouldn’t say alive or dead, the guy who asked his brother Yunyan about the activity of great compassion, the guy who asked the sweeping Yunyan what he was doing. Daowu was a successor to Yaoshan in the Shitou branch of Zen, the branch that eventually became associated with “silent illumination” and then radicalized by Dogen as “shikantaza” (or earnest, vivid sitting).

Shishuang was a contemporary of Linchi, Yangshan, Dongshan and Xuefeng – living and teaching right in the thick of the dream time for Zen teachings.

There’s a number of significant and hinky context bits in this old story. Succession to the abbacy appears to be by group consensus and so the Shishuang line may not be thriving in an imperially controlled monastery but at the fringes. Perhaps this allowed for the fringe practice of monks dying while sitting or standing. A practice experiment that one might say “died out” (I hear you groaning!).

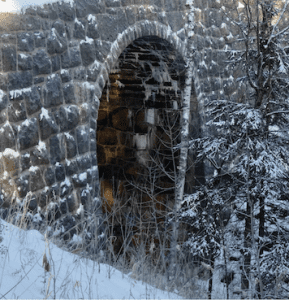

Thus Shishuang’s zendo was reputed to be a dead-tree hall, so named for the emphasis on long hours of still sitting and fore-shadows the silent illumination school (although these old guys were dead for a hundred years or so before the silent illumination brand arose) as well of this drop-dead trick – a considerable meditation feat and quite beside the point.

James, of course, does a nice job of laying out the issue and making the koan point that the realization of emptiness is alive:

“How do you extinguish all delusive thoughts? Show me. How do you let consciousness expire? What word expresses that? And what about the ten thousand years? Ten thousand moments? Ten thousand breaths? Ten thousand pauses? I can tell you just presenting zazen will not cut it.” [emphasis added]

Nor will dying in body or in spirit while sitting necessarily do it.

And this goes to the heart of shikantaza. Demonstrably not simply a silent illumination death camp (aka”just sitting”) – a passive practice in the chorus of the do-me-dharma school.

“Dropping body and mind,” Dogen’s mantra for shikantaza, echoes the withered tree way but is certainly not merely pure receptivity or panoramic awareness as some contemporary skin bags portray it.

Another framing for this conversation is about the two wings of Buddhist meditation, samadhi and insight, that has been in play at least since the Buddha’s time. We tend to emphasize one over the other, subtly missing the heart of the wondrous method.

Soto Zen at it’s best leans toward samadhi. Koan Zen toward insight.

Case in point, a close student of Suzuki Roshi once told me that he told her, “Zazen is samadhi.”

Yes and no.

I once asked Katagiri Roshi if zazen was about samadhi or insight. He held up his hand and turned it back and forth and said, “Like a leaf showing one side then the other. Go into one side deeply and the other appears.”

And this is Dogen’s great practice. Shikantaza as the “show me,” “tell me” resolution of the samadhi/insight issue where samadhi and insight are two foci and the seeming conflict is dynamically resolved through ongoing intimate interaction.

It is this very churning that ripens the sweet cream of the long river.

(Photo above of withered tree is from recent canoeing trip to BWCA)