There is a long-standing debate in Soto Zen circles about Dogen and the use of koans.

There is a long-standing debate in Soto Zen circles about Dogen and the use of koans.

Dogen, you see, is regarded these days as the founder of the just-sitting school of Zen (Soto) and his writings are used (selectively – I’d argue) to paint the great founder advocating for the style of zazen he taught, shikantaza, and the style that characterizes the modern Rinzai school, koan introspection, as different and not equal. This narrative became dominant about two hundred years ago – 550 years after Dogen’s death.

This characterization, however, is unfair in many many ways. We know, for example, that there have always been Soto practitioners engaged in koan introspection, (e.g. the 18th Century Soto masters Genro and Fugai wrote The Iron Flute:100 Zen Koans), especially since Harada Daiun’s time, beginning about a hundred years ago.

In this post, I reveal the ultimate argument that will definitively and for all time prove that Dogen was really a koan teacher or that, as I believe, koan and shikantaza were not different practices for him.

Or it might at least provide a little more fuel to the already convinced. You get to judge. This is the internet, after all.

Before I get into that, though, I want to admit that it really doesn’t matter. Koan introspection has a profound integrity that does not need Dogen’s approval. For those of us who are deeply moved by Dogen’s teaching, however, there is a yearning that the old boy’s work be represented fairly and accurately and not be misappropriated for a sectarian political agenda.

Oh, yes, but what about the smoking gun?

First we need some background, a baseline for comparison, if you will. I’ve selected a couple passages by a koan teacher so we can hear what s/he might sound like so that we can contrast it to Dogen and appreciate the difference heard by many modern Soto folks. So the following are by a teacher of about the same dates as Dogen who advocates for koan introspection:

Good gentle people, when you meet a teacher, first ask for a kōan, and just keep it in mind and study it diligently. If you climb to the top of the mountain and dry up the oceans, you will not fail to complete this study.

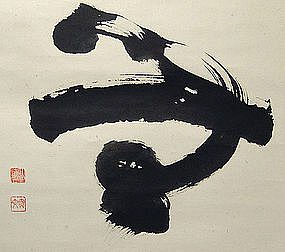

And specifically regarding the mu koan (like the “mu” calligraphy above by Yamada Mumon Roshi), here’s that same koan teacher:

A monk asked Zhaozhou, ‘Does a dog have the Buddha nature?’ Zhaozhou answered, ‘Mu.’ Can you gauge this word, ‘mu’? Can you contain it? There is no place at all to grasp its nose. Please try letting it go. Let it go and just look. What about your body and mind? What about your conduct? What about life and death? What about the dharma of the Buddha, the dharma of the world? What about, after all, the mountains, rivers and great earth, the men, beasts, houses and dwellings? If you keep looking and looking, the two attributes of motion and rest will naturally become perfectly clear, without arising. Yet, when these do not arise, this does not mean that one becomes rigidly fixed. There are many people who fail to realize this and are confused about it. Students, you only attain it when you are still half way; when you are all the way, do not stop. Press on, press on.

Now for the surprise – the above passages are by the koan teacher named Dogen. The first passage is from Dogen’s Extensive Record, p. 528, the second (which I’ll focus on) is from “Guidelines for Studying the Way, 8, The Actions of a Zen Monk.” There are many more possible examples including more than 30 times in the Shobogenzo where Dogen admonishes his readers to “sit quietly and reflect” many different koan topics.

Sometimes orthodox Soto teachers, bent on explaining away the obvious (sweating and shifting on their zafus), argue that in the second passage, when Dogen says, “Let it go and just look,” he’s encouraging his students to let go of mu and practice shikantaza.

One problem with that theory is that it goes against what is known about the context in which “Guidelines for Studying the Way” was written in 1234. This text was addressed to the group of monks living with Dogen at his first monastery near Kyoto and therefore was not included by Dogen in the draft Shobogenzo that he pulled together before he died. “Guidelines” appears to have been originally intended as an in-house document, not directed for a general audience.

Even if we read the passage as Dogen telling the monks in his monastery to stop practicing mu, there’s a problem – where might they have gotten the practice from in the first place?

Dogen’s first Zen teachers, Eisai and Myozen, from whom he received a Huanglong Rinzai lineage, had both been dead for some time. It appears that Eisai had other successors, though, so maybe the monks had learned of koan introspection from them. However, in the writings left by Eisai, there are no references to koan introspection. None. We don’t know what Dogen and Eisai’s other heirs were doing while they were studying with Eisai and Myozen. It may have been the Huanglong style of koan introspection (Heine calls it the “entangling vines” approach) or it may have been a more generic form of Zen meditation common on the continent.

Nevertheless, what we know of the monks in Dogen’s assembly does not indicate that they had generally come from some other successor of Eisai or Myozen.

But if not from the Eisai line, maybe the monks had picked up koan introspection from another Rinzai line. However, it doesn’t appear that there were any in Japan in 1234, with the exception of the renegade Daruma-shu, but the teacher there, Nonin, had not gone to China and seems to have had a rather one-sided absolutist view so it seems very unlikely there was any koan introspection going on in the Daruma-shu.

But how about the important Enni Bennen, the Rinzai teacher who eventually had 30-some successors and was given the big monastery in Kyoto that Dogen is reputed to have had his eye on? Well, in 1234, Enni was just tying up his straw sandals and heading for China.

So where, oh, where could the monks in Dogen’s monastery have received instruction in the mu koan? The only likely place, imv, that they could have picked up mu practice to begin with was from the only monk known to have studied in China with a teacher who is known to have advocated for practicing mu. That teacher would Rujing and the Japanese monk would be Dogen.

Furthermore, it is more than a stretch to view the passage above as discouraging koan introspection. Instead, the more likely explanation, is that Dogen was giving his monks good advice for how to practice with mu – when you approach getting hold of mu, let go and look! And then Dogen jumps in much like Hakuin might with a series of questions to test and open up a student’s realization (aka, checking questions):

- What about your body and mind?

- What about your conduct?

- What about life and death?

- What about the dharma of the Buddha

- What about the dharma of the world?

- What about the mountains, rivers and great earth, the men, beasts, houses and dwellings?

Indeed, some of these echo checking questions in our Harada-Yasutani koan curriculum.

So this passage from “Guidelines,” in context, is the smoking gun in the Dogen-koan debate. Dogen even seems to have taught mu to his students.

But whether Dogen was a koan teacher or not, the most important point is that we take up the dharma and practice with diligence – all the way through – with koan or without. And to paraphrase Dogen, not stopping at the stage of belief but continuing through the halfway realization, pressing on and on.

As Dogen said elsewhere, “The gates of emancipation are open and the truth is ready to harvest.”