Which also helps explain why when the Catholic Church holds a teaching as being true, there will be no modification of it. I’ll discuss a few examples of this in the near future.

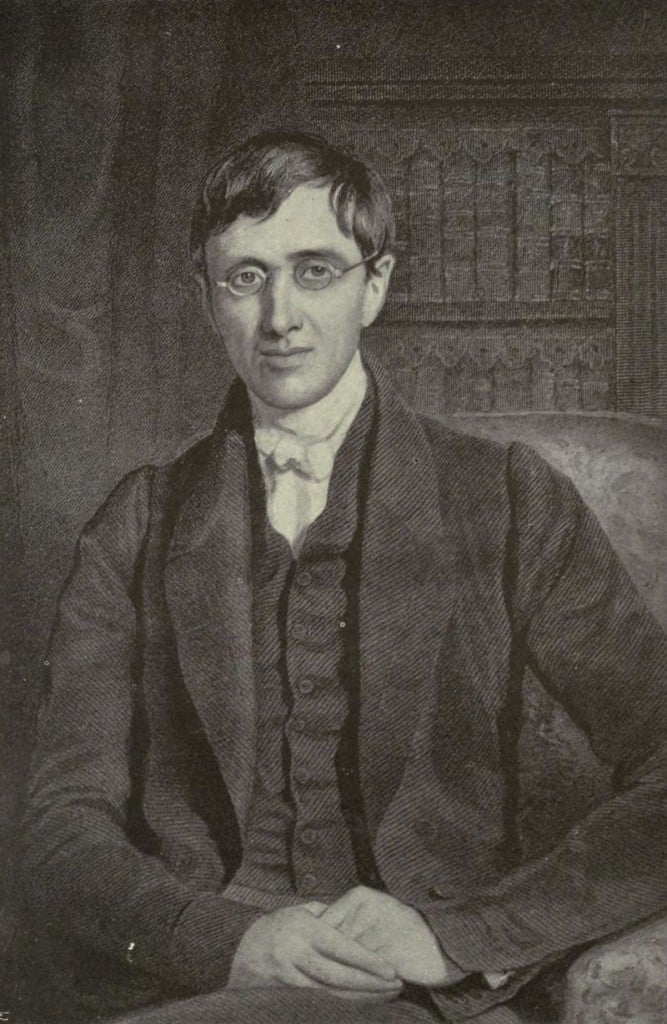

But first, Monsignor Benson, a convert from the Church of England, helps make it clear for Christians of all stripes how the Church interacts with the Deposit of Faith. Especially in terms of when She speaks as the voice of Christ to the world.

This is an excerpt from his book, Christ in the Church. The volume is a collection of essays published in 1911. The preface to the work notes that the ideas contained in the essays were delivered in sermon form during the season of Lent in 1909, in the church of St. Silvestro-in-Capite in Rome; during Lent in the year 1910 at the church in Kensington, and in a private household in Boston “in Eastertide that same year.”

What follows is from the later part of chapter two, and the first part of chapter three,

To the Protestant, Christianity consists in the union of the individual with Christ — of individual with individual — that, and no more. A Divine Person, he asserts, lived on earth two thousand years ago, performed actions, spoke words, finished His work, and went back whence He came; and true Religion consists in the adherence of the human unit to the Divine Person, with no priest, prelate, church or sacrament, since none are necessary.

[Note]I am aware that some branches of non-Catholic Christianity— notably among the Anglicans — repudiate altogether this individualism in religion. They, too, claim to adhere through the living Church to Christ, and to be members of that Mystical Body in which He dwells. But I am not here concerned with that claim, though personally I do not believe it. It is not my object, as I have already said, to attack in any way other religious bodies, least of all those who hold so much of Christianity in common with Catholic Christendom. It appears to me, as well as to practically all the rest of both Catholic and Protestant Christendom, that the claim is an impossible one, and that it has not the logicality of either side; but I do not propose to discuss this. It is possible that later on in these lectures a good deal that I have to say will indirectly militate against the Anglican position; but I am concerned here only with the two clear-cut conceptions of Christianity as they have always existed amongst us from the Reformation down to the Tractarian movement — the Catholic and the Individualistic.

Now, the Catholic idea is far larger, as it seems to me, and also simultaneously far more simple, as well as far more elaborate, than the Protestant. For the Catholic, Jesus Christ still lives upon earth as surely, though in another and what must be called a ” mystical” sense, as He lived two thousand years ago. For He has a Body in which He lives, a Voice with which He speaks. As two thousand years ago He assumed one kind of Body by which to accomplish His purposes, so He has assumed now another kind of Body in which to continue them; and that Body consists of an unity of myriad cells — each cell a living soul complete in itself — transcending the sum of the cells and yet expressing itself through them. Christianity, then, to the Catholic is not merely an individual matter — though it is that also, as surely as the cell has individual relations with the main life of the body. But it is far more: it is corporate and transcendent.

The Catholic does not merely as a self-contained unit suck out grace through this or that sacramental channel; the priest to him is not just a vicegerent who represents or may misrepresent his Master; a spiritual life is not merely an individual existence on a spiritual plane. But to the Catholic all things are expanded, enlarged, and supernaturalized by an amazing fact: He is not merely an imitator of Christ, or a disciple of Christ, not merely even a lover of Christ; but he is actually a cell of that very Body which is Christ’s, and his life in Christ is, as a matter of fact, so far more real and significant than his individual existence, that he is able to take upon his lips without exaggeration or metaphor the words of St. Paul —” I live — yet it is no longer I that live; it is Christ that liveth in me “; he is able to appreciate as no separatist in religion can appreciate that saying of Christ Himself, that unless a man lose his life, he cannot save it.

Still, to the eyes of the Catholic, there moves on earth that amazing Figure whose mere painted portrait in the Gospels has driven men — artists, seers, and philanthropists — mad with love and longing — and he is part of it. There still sounds on the air the very voice that comforted the Magdalene and pardoned the thief: the same Divine energy that healed the sick and raised the dead is still active on earth, not transmitted merely from some Majesty on high, but working now, as then, through a Human Nature that may be touched and felt. If the Catholic be mistaken in this astounding vision, yet at least he cannot be accused of substituting a system for a Person, since it is the groundwork of his whole life and hope that what men call a system is a Person, far more accessible, more real and more effective than one can be who is thought to reign merely in a distant heaven, and no longer in any real sense to be present on earth. The true minister of every sacrament, for example, as every Catholic believes, is none else than the supreme and Eternal High Priest Himself.

This is an amazing claim. It remains now to consider some conclusions that will follow from it if it can be accepted as a working hypothesis.

****

We described in the last chapter the claim of the Catholic Church to be the mystical Body of Christ in which He lives, speaks, and acts. We have not yet advanced any arguments, beyond a few suggestive sentences of Scripture and a physical analogy or two, in defense of that claim (the time for that will come later) ; we have merely stated the position. But before passing on to these arguments it will be illuminating to notice how two or three further claims made by the Catholic Church, and usually considered as obstacles to her acceptance by the world, are, as a matter of fact, inevitable consequences of her fundamental position.

I. It is perfectly plain that if the Catholic claim to possess Christ in what may be called His ” Church Body” be accepted hypothetically, exactly the same authority must be predicated of the voice of the Church as of the Voice of Christ. (I do not mean by this that Catholics hold that the Church is capable of giving new truths to the world unknown to the Apostles; only that in declaring authoritatively what was that Revelation originally given by Christ, she is as unerring as was He.) This is nothing else than that supreme stumbling-block which Protestants know as the doctrine of the Church’s infallibility. Now from the Protestant standpoint the doctrine of Infallibility is, rightly, absurd and even blasphemous. Granted their premisses, their syllogism is perfectly sound. All men are liable to error; the Church consists of mere men; therefore the Church is liable to error. But on the Catholic premisses, Infallibility is simply inevitably and obviously true; for if it be granted that the cohesion of men in the Catholic Church ascends into and is met and transcended by a higher personality, like a cohesion of cells in an organic body, and that higher personality a Divine and infallible one, it follows that the decision of that organic body is the decision of infallible God. If infallibility be predicated of Jesus Christ, it must be predicated of Him in His Mystical as well as in His Natural Body.

That such a transcension of the sum of component cells is possible — that is to say, that the judgment of a number of persons acting in concert is universally recognized as being at least of more value than the mere sum of their votes — this fact is illustrated by the jury system in use in most civilized countries. We give without hesitation to twelve men acting in concert a power over life and death which we would not willingly give to any one of the men taken by himself. It is true that we do not attribute to a jury actual infallibility, since we have no reason for believing that their united judgment has a promise of being ratified and safeguarded by a higher tribunal than that of human opinion, though we believe that that method of decision arrives as nearly to perfection as is possible to obtain; but, ex hypothesi, Catholics believe that the consent of the Church does rise to that higher plane — that the sum of Catholic opinion as expressed, let us say, through a Council, does actually rise to a superhuman level of consciousness, that the sum of the human cells mounts up, as in an organic body, to a new unity of life, and that that life is identified and united with a Divine One. “He that heareth you, heareth Me. … As my Father hath sent Me, even so send I you.” “I am the Vine: you the branches.” Infallibility, then, on the Catholic hypothesis is inevitably an endowment of that Body in which there thinks and speaks the Mind of God. If there be such a Body it must be infallible.

Points #2 & #3 later.