The average person, even if he or she is an avid cinephile, really sees a very small percentage of the films released every year. Add to that fact that more and more viewing is done via DVDs, streaming, and other methods, and the percentage of one’s viewings that constitutes new, theatrical releases appears to be very small.

If an end of year, Top 10 list is an exercise in self-definition, a favorite discoveries list is that and more. It allows the critic to highlight films mostly available to the public. Even if readers can’t go to festivals or hunt down yet to be distributed independent films, they have a plethora of great viewing options.

Each year, to accompany my annual Top 10 list, I present my favorite discoveries of the year. These are films that are not new but which I saw for the first time during the previous year. Sometimes they are recent films that fell through the cracks in the preceding film season. Sometimes they are classics that became available for the first time. Often they are gems that had been there all along and which I think are solid viewing options for those who who want some variety in their viewing diet. Here were my favorite viewing experiences of 2009 from among “new to me” films.

10) The Station Agent (2003) — Thomas McCarthy

I sought out this film in the wake of being bowled over by McCarthy’s more recent film, The Visitor. Like that film, The Station Agent is more about character than plot, and like in The Visitor, the characters in The Station Agent have been wounded by life and yet find a new love for it by finding purpose in being there for others. McCarthy was given a story credit for the Pixar film, Up, and he appeared as an actor in Season 5 of the acclaimed HBO drama, The Wire. The Station Agent is his only other directing credit besides The Visitor, but 2010 is supposed to bring a television series called Game of Thrones to which he is directing. Based on his previous work, it should not be missed.

The film has stand out acting from Peter Dinklage and Patricia Clarkson, and there is even a small part for a young Michelle Williams. Hindsight is always 20/20, but it is nevertheless always interesting to see how many actors in small, independent films went on to larger success. That usually says something about the director’s eye for talent, doesn’t it?

9) Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957) — John Huston

One of my favorite autobiographical film stories relates to watching The Godfather while just out of high school, knowing Al Pacino only through films like Dick Tracy, Author! Author! and Sea of Love. “Oh, so that’s what they were talking about,” I said of the legions of older, more experienced viewers who had insisted (to my initial befuddlement) that Pacino was a major talent.

Well it took me a little longer to catch up with Robert Mitchum, knowing him primarily through the television series The Winds of War and an overwrought remake of Cape Fear starring Robert DeNiro. Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison seems like a clear attempt by John Huston to replicate the formulaic elements of The African Queen: rough guy, unattainable woman, and the crucible of war keeping them together. It is probably only because the Bogart-Hepburn vehicle is so beloved that Allison is not better known or appreciated. For my money, Deborah Kerr is every bit as good as Hepburn (who always strikes me as her most priggish in Queen), but it is Mitchum who is a belated revelation. One of the real pleasures of Heaven Knows, Mister Allison is that it follows its premise all the way to the end, and it allows both characters to remain intact rather than copping out with an eleventh hour transformation that would have made a different ending possible but rendered the whole movie a cheat. There is a decency about these characters that is often missing in modern love stories. It is a nice illustration about love leading one not just to care about another person but to care about what they care about.

8) A Good Marriage (1982) — Eric Rohmer

A Good Marriage is the second film in Eric Rohmer’s Comedies and Proverbs series. The reason I picked this particular film is because I was struck while watching it how it was the same as and yet different from Rohmer’s films in the Six Moral Tales cycle. The similarity comes in that it is firmly grounded in the problems of love in contemporary France. Here, the main character is a woman, though, and I think Rohmer does an excellent job in allowing the story to unfold from her perspective. If Sabine is slightly more sympathetic than some of Rohmer’s earlier protagonists, perhaps that is because one sympathizes with the contradictory advice she receives from friends and the way in which she must negotiate an obstacle course of expectations based on sexual liberation and sexual stereotypes. The film is set in motion by Sabine’s resolution to avoid affairs with married men, and her realization that getting a man is not nearly as hard as getting a good marriage.

Pauline Kael practically made a career by slamming Rohmer’s films as more dull than watching paint dry. To me, though, Rohmer is the film maker that Woody Allen was always trying to be–funny, sad, self-deprecating, and able to do endless variations on similar themes without falling into shtick or mere repetition.

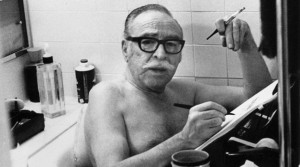

7) Trumbo (2007) — Peter Askin

I somehow managed to miss Trumbo both when it played at The Toronto International Film Festival and, later at the Full Frame Documentary film festival. It is a terrific documentary, using the letters of the famed writer to sketch a portrait of his life as a blacklisted screenwriter and clips of films penned by Trumbo to show how those experiences informed his writing. It is also a terrific drama, as some of the great actors of our generation recite monologues from the letters. Joan Allen, Donald Sutherland, Michael Douglas, and Nathan Lane (among others) all lend their talents to bringing to life Trumbo’s words.

One of the stand out moments in a film full of stand out moments is when Donald Sutherland reads a reflective letter from Trumbo about aging. Another is when Kirk Douglas, struggling mightily against speech impairment from his stroke, shares how one’s impending death can make one take stock of what he has done in his life that he is proud of. For Douglas, that meant hiring the then blacklisted Trumbo to write the screenplay for Spartacus.

Full review here.

6) Fallen Champ: The Untold Story of Mike Tyson — Barbara Kopple

The release of James Toback’s film about Tyson prompted a renewed interested in the boxer, and it was part of what prompted Steve James to include this inexplicably not yet available on DVD Kopple piece in his series on sports documentaries at last year’s Full Frame Documentary Film Festival.

I wrote more extensively about the film in my wrap up of the festival, and rereading that piece reminds me of how frequently gender roles and conflicts play a role in the subjects Kopple picks and yet one seldom thinks of her as a “female director.” She is just a great director. Period.

Kopple did a fantastic Q&A session after the film’s screening, and in it she showed a self-effacing quality that must serve her well as a documentarian. Even when the purpose of the meeting was to honor her and her work she was drawing people out, getting them to share their stories, and making them feel listened to rather than preached at. She has been doing some more television work, including a film about the wife of the D.C. Sniper, and an installment of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series about the Steinbrenners.

5) The Sound Barrier (1952) — David Lean

I had some brief discussion of this film at Cinevox, so I’ll put in a plug for that discussion board here.

I had some brief discussion of this film at Cinevox, so I’ll put in a plug for that discussion board here.

Lean’s early films were a very interesting discovery for me. One can see the attraction to the big themes that is quintessential Lean, but there isn’t the bloated quality that one finds in Lean at his worst–when he’s always trying to top Lawrence of Arabia by adding more.

The film is about attempts to break the sound barrier, and it has the tone of The Right Stuff combined with Capra’s Why We Fight series. One thing I like about these older movies is how often the supporting characters are treated with dignity, as real people, and not merely presented as one-dimensional obstacles for the heroes to have to negotiate.

Yes, some of the appeal is in the dramatic irony of knowing what is on the horizon for the director, but that works for the film as well in a sort of reflexive way, really reinforcing the dramatic theme of mavericks on the verge of a great breakthrough.

4) The Servant (1963) — Joseph Losey

I have been working my way through an anthology of interviews with film directors as a way of familiarizing myself with some auteurs whose work I haven’t yet been exposed to in any sort of systematic way. I watched maybe a dozen Losey films last year, and The Servant was the one that stood out the most to me.

I’m not sure whether or not that is a good thing. It is such a distinctive film in its visual style and approach is so wrapped up in preserving the homoerotic core of Robin Maugham’s novella while passing for something else in a Celluloid Closet kind of way. In fact, the film would probably be valuable as a case study in how homosexual content got transferred to the silver screen in the 1960s even if it how no intrinsic value. The performances by Dirk Bogarde and James Fox are noteworthy, but it is in watching Losey struggle with the technical problem of how to say clearly what cannot be spoken and so must be implied formally that the film most fascinates.

3) On Dangerous Ground (1952) — Nicholas Ray

Most people know Nick Ray only through Rebel Without A Cause, which is a shame. Last year saw Bigger Than Life get restored and re-released, and Johnny Guitar (review by Katherine Richards) continues to find a spot on Turner Classic Movies list of films readers most wish would get a DVD release. I found myself drawn to Ray’s genre pieces. The Flying Leathernecks shows him working within the context of a war film; The Savage Innocents was a nature film that got Ray a nomination for the Palme d’Or. Party Girl has Cyd Charisse dancing and a mobster love story. And then there’s the noir.

On Dangerous Ground has a typically hard-boiled protagonist; Jim Wilson (Robert Ryan) is a cop about to explode. He is sent to investigate the murder of a girl in the wintry countryside. The case, as it so often is in noir, is a mere cover for the relationship that forms between the man and the woman whose path intersects his own. In this case the woman is Mary Malden, the blind sister of the murder suspect. It is in dealing with Mary that Jim feels his last, tenuous thread to his own humanity. Will it snap, or will it lead him back from whatever abyss his rage is hurtling him towards?

The plot is fairly conventional for noir, but the film work is stunning. It uses a lot more location shots than I’m used to seeing in most films of the time period, and it thus really conveys a sense of place and mood.

2) Nobody Knows (Dare mo shiranai)(2004)–Hirokazu Koreeda

Koreeda’s Still Walking was one of my Top 10 films of 2008 (it’s also making some critics’ 2009 list since it received limited post-festival release last year). It’s no surprise then that I tried to see as many Koreeda films as I could get my hands on after screening it. (I also tried screened a few hard to find Mikio Naruse films, since Koreeda said he felt more kinship with Naruse’s films than Ozu’s when asked about inspirations in his TIFF question and answer session.)

The plot revolves around a single mother who tries to sneak her children into a Tokyo apartment and then (perhaps) abandons them to fend for themselves. This set up allows Koreeda to do what he does best–show innocent characters exploring a landscape familiar to us but new to them. (There is a similar structure at work in 2009’s Air Doll.)

I’m not normally a big fan of films about children; I tend to think they get sentimentalized in ways that I find trying. Here, though, the circumstances of the children provides a natural pathos, while the restrained camerawork shows both the gradual decay of their environment and their heroic attempts to rise to a challenge they barely understand. Nobody Knows is a stunning and compassionate film from a director who earns emotional responses rather than wrenching them from the audience with sledgehammer techniques such as bombastic soundtracks and unrealistically smooth speeches.

1) The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933) — Frank Capra

Here is another film not readily available on DVD. If you are fortunate enough to find a VHS copy, grab it. It is probably the same ethnic and racial sensitivities that dogs Disney’s Song of the South that keeps General Yen out of DVD collections despite the prestigious reputation of its director.

Barbara Stanwyck plays Megan, the fiancee of a missionary who ends up the captive of a dictatorial Chinese general fighting a civil war. In my review of the film, I mostly spoke of it as a Frank Capra picture, meditating on how it fit in to his substantial body of work. This film also led me to Capra’s The Miracle Woman, and its worth mentioning here that these two films alone are enough to make me wonder why Stanwyck’s name is not uttered with the same hushed, reverential tones used to invoke the names of Bette Davis and Katherine Hepburn. Stanwyck was nominated four times for the golden statuette given to the Best Actress in a motion picture, but she never won. On a lark, I looked up the Academy Awards for 1933. Sure enough Hepburn took the award–for Morning Glory. (Never heard of it? Join the club.) Perhaps more interesting is the fact that Capra was nominated, but not for The Bitter Tea. His Lady for a Day was released the same year, and apparently the depression era fantasy (later remade as Pocketful of Miracles) was deemed more worthy than the interracial love story.

Over seventy years later, I screened both films. The one that got the glory now seems a bit conventional and a bit forced. The one that languishes in the vault is complex, moving, and still relevant. Even then, the relationship between Oscar nominations and quality of films was tenuous at best.