In 1990, an anonymous author wrote a blistering manifesto entitled QUEERS READ THIS. In the 13th century, an anonymous author collated dozens of Icelandic poems in a 45-page vellum manuscript known as the Codex Regius.

Walk with me; I know the road.

There’s no right way to be marginalized. There is no version where you are greeted kindly by the authorities and told you’ve done a good job and they’ll let you into the clubhouse now, meek and pliant but alive. The kindest thing they want for you is subjugation, and most of them want blood. Oh, they’ll dress it up civilized and pretend all day that they aren’t licking their teeth waiting for you to stumble, yearning for the slightest hint of an exploitable weakness. Some of them will even believe it until they get that opportunity– but at the end of the day they want you silent and invisible, and the best kind of silence and invisibility is death, preferably with a rousing hunt beforehand.

(This is where we talk about intersectionality, and the fact that you can be– almost certainly are– both of these people. You’re not a rabbit approaching a snare, and you’re not a wolf prowling the perimeter. You are a fox. Whether you get to eat or be eaten depends entirely on what company you’re in. Accept that about yourself and move on.)

QUEERS READ THIS was written the year I was born, three months before I refused to turn in my mother’s womb and had to be cut out of her whole and alive. I hope like fire that the people who wrote it are still alive and still furious and still fighting. It’s a primal scream– just a full-throated roar of anger and pain and stubbornness, a desperate messy hate-love letter to its own blood. It was printed on twelve pages and distributed at a NY Pride March by Queer Nation, a direct action activist group born out of the AIDS crisis.

This is how it starts: “How can I convince you, brother, sister that your life is in danger: That everyday you wake up alive, relatively happy, and a functioning human being, you are committing a rebellious act.”

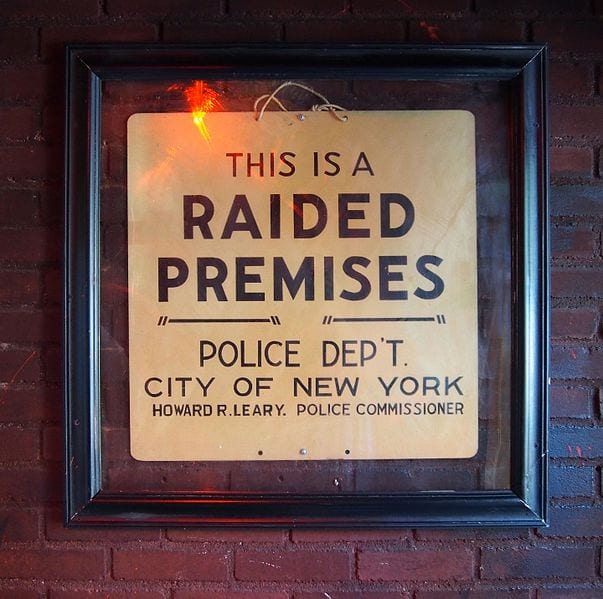

Of course all history is queer history– we didn’t spring into existence in the 20th century, fully-formed and unacceptable, like peerless Athena from her father’s headache– but if we have to choose a starting point, at least for the US, Stonewall is as good a place as any to begin. In 1969, a group of NYPD officers literally called the Public Morals Squad invaded the Stonewall Inn, a Mafia-owned establishment notorious as a haunt for the suppressed queer community, and began the usual attacks on the patrons. This time some spirit of rebellion stirred, and as the crowd surged to outnumber the police by hundreds, one unknown woman was dragged out fighting all the way. She called out to the restless onlookers, “Why don’t you guys do something?”

So they did something.

What they did was start a riot, a violent backlash against violence that spilled into the following nights. It was instigated by gay street kids, by prostitutes, by drag queens and trans people of color– by the most marginalized fringes of a marginalized community. They forced the officers into open retreat, and even after reinforcements arrived to rescue them the mob chased police cars through the streets. By the next year, what had been a meek and polite movement begging for recognition ignited the first Pride marches on the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

I don’t repudiate that violence– that violence was earned– but it’s not why I’m mentioning Stonewall. The reason I’m mentioning Stonewall is the gay street kids, the prostitutes, the drag queens and trans people of color. The reason I’m mentioning Stonewall is that we don’t like to talk about who was in the trenches doing the fighting.

The Codex Regius contains 31 poems, among them Havamal, “the sayings of the High One”. Although these verses do not contain specific attribution, they are generally understood as intended to be the advice of Odin on many subjects.

Chisholm’s translation of Havamal opens with the following warning:

Watch out and check all gates before faring forth.

One should spy around,

one should pry around.

Hard to know what foe

sits before you in the next room.

(It’s not paranoia if they’re really after you.)

Let’s talk about Odin. Better yet, let’s talk about queer Odin.

Odin has many names– One Eyed, Wanderer, Raven God, Glad of War, Sage, Terrible One– and among them, distinctive even among this range, is Jálkr, which means “Gelding”. A little at odds with the popular image of the Norse gods as macho manly men, this is thought to be a reference to Odin’s seidhr work– a kind of ecstatic magic associated with female sexuality which he learns from Freyja, and which he must transgress gender and sexual boundaries in order to perform. This transgression places Odin– the High One, the Roarer, the Allfather– beyond the fringes of the social mores of his society, which condemned such behaviour as ergi, unmanly and unacceptable. And yet Odin remains all these things– he is the lord of his peers, the wise counselor, the war god that men turn to for battle frenzy and victory and a place in his hall when they fall. And he is also, simultaneously, the strange witch with weird ways, the dangerous outlier tricking men into his schemes and his bed.

He would have been right at home at a riot where drag queens threw bricks at the cops, is what I’m saying.

Two-thirds of the way through QUEERS READ THIS, we get to my favourite part.

reeuQ yhW

Queer!

Ah, do we really have to use that word? It’s trouble.

We’re in it now. You watch where you’re going; I’ve got a map.

“Queer” might feel like an ubiquitous word today– it’s the default in academia and entertainment, enshrined in Queer Theory and Queer Eye– but here’s a shock for you: not so long ago, queer was a slur. (This, of course, is not its origin– originally is just meant “strange”– and like nearly all the language we have to describe ourselves, it’s gone through stages, slur and identity, identity and slur.) I know, you’re stunned. It was the shot in the sling, flung at anyone who upset the status quo, alongside such gems as faggot, dyke, and now even-more-ubiquitous gay. It meant “I hate you”. It meant “die”.

And then we reclaimed it. (Again.) Linguistic reclamation is a process by which the language of the oppressor is stolen, inverted, and used to empower the disenfranchised. Reclamation does not mean that the word will never be used in its previous pejorative context, or that it is free for everyone to use– and since reclamation is a process, there is usually a delay while the word’s meaning is adjusted– but it aims to take the teeth out of the term. With the modern reclamation of queer, starting in the 1980s and spearheaded by Queer Nation, it gradually grew into an umbrella term that shelters a wide range of marginalized identities– gay men, lesbians, bisexuals and pansexuals, transgender and nonbinary people, and the asexual and aromantic spectrums, just as examples. It was particularly embraced by queer people of color, and by the outlying fringes of the community, who were often thrown under the bus. (You know, the ones who started Stonewall; the ones who fought back.) To be queer is to be part of a community that is aggressively inclusive, that demands space for everyone and won’t be satisfied with the scraps passed beneath the table by our upscale LGBT+ cousins who are able and willing to blend in with the straight authority.

As the authors of QUEERS READ THIS say, “[…] when spoken to other gays and lesbians it’s a way of suggesting we close ranks, and forget (temporarily) our individual differences because we face a more insidious common enemy. Yeah, QUEER can be a rough word but it is also a sly and ironic weapon we can steal from the homophobe’s hands and use against him.”

At around the same time that the queer community was finding its teeth, starting mostly in the late 1960s with Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, a similar process of reclamation was taking place in the Pagan community. “Pagan” has gone from a Latin word (paganus) that meant “rural person”, to a pejorative term suggesting that a person had “no religion” (or at least not the correct one) to the updated “neo-Pagan” meant to differentiate between ancient non-Christians and modern ones, and has in the modern day been reclaimed by the practioners of modern Pagan religions and practices. Like queer, it has become an umbrella term that applies to a huge motley family of semi-related identities– witches, Wiccans, and Druids, reconstructionists and revivalists, we can all fit into what John Beckett calls the “Big Tent” of Paganism.

The umbrella also serves an important purpose in, well, keeping the rain off. It’s a kind of pack security. If you’re queer, you have an automatic pass into that vast community. Ideally, you should then be able to trust other queer people, regardless of our specific granular identities, to come to your defense when you’re attacked by our mutual enemies; and vice versa. These community terms put a gentle blur filter over our perceptions of each other, enough to remember that despite our (sometimes substantial) differences, we’re all in this shit together.

The vagueness of the term is the point. The bigness of the tent is intentional. The inclusiveness is why these words matter.

Have another excerpt from QUEERS READ THIS: “There is the one certainty in the politics of power: those left out of it beg for inclusion, while the insiders claim that they already are.”

Alright, this is our turn-off. This is why I’ve been walking this stretch of road and dragging you with me.

I have a visceral hate reaction to Laura Tempest Zakroff’s term “p-words“. I have loathed it with every fiber of my being since I first encountered it, and every time I see it my stomach sinks and I feel that unsettling chill spread through my ribs, a whole body response of rejection that it took me a couple of years to untangle.

See, there’s a movement in some corners of the internet to replace the word “queer” with “q-slur“. It’s largely young people, mostly part of the LGBT+ community, who all spontaneously woke up around in the mid 2010s and realized that queer was a mean word that we should stop using! This is, of course, about 30 years late as realizations go, deep into queer’s reclamation as an identity, but because society at large still doesn’t trust young people with queer adults, most of them don’t know much– if anything– about our history.

The current reclaiming of queer has always had detractors, for various reasons– there are plenty of LGBT elders who still reject it– but this specific wave likely started with TERFs (that’s trans-exlusionary radical feminists, if you’re unfamiliar) as hostile rhetoric targeting the extra-marginalized corners of the queer community. (Go ahead, guess which corners.) As exclusionists do, they are aiming to narrow the definition of the community to only include their prefered, safe, respectable members– a broad umbrella like queer, that not only supports but celebrates and embraces the fringe, is a danger to that ideology. By shoving queer back into the slur category, they’re attempting to shove trans people (and anybody else they aren’t keen on) out of the community. Unfortunately, because of the previously mentioned lack of good youth mentorship, a lot of kids are reading pearl-clutching TERF content about the offensive, dangerous word that everyone is inexplicably using, and they’re taking it as gospel and trying to shame their own community. Their rallying cry is “queer is a slur”, and everywhere they see it in use they replace it with “q-slur”.

The fact that this is deeply invalidating and retraumatizing to people who have reclaimed queer as identity has not occurred to them, presumably.

(It’s not paranoia if…)

This is an ongoing fight that I have an unambiguous position on, which you can probably figure out by now, but for the record: I’m queer, it’s the queer community, queer is a reclaimed word that the oppressors can’t have back. My city now.

Now, I don’t think “p-words” has anywhere near as insidious an origin as “q-slur”– according to Zakroff, it was born out of frustration with intra-community arguments about what counted as Pagan, and I get the impression that it’s more sarcastic than anything– but it’s got a very… familiar flavour. And having finally identified why it makes me want to simultaneously peel my skin off and bite someone, I’m concerned about the potential implications. Not so much of Zakroff’s thing specifically– although I still hope that it dies out because I hate seeing it– but about the fragmentation I’ve noticed in the community.

It’s normal, and useful, for large communities like ours to develop increasingly granular internal divisions. Having one of these identities doesn’t preclude you from having a more granular one within it. I’m queer and agender; I’m Pagan and Heathen– a veritable matroyshka doll of identities. But while the more granular identity is useful inside the community– saying I’m agender means something specific and significant to other queer people; saying I’m Heathen tells other Pagans something useful about how I practice– it’s less useful outside of it. An outsider might not know those more narrow, specific terms, but they’re more likely to be familiar with a broad identifier like Pagan or queer.

And there are, frankly, not that many of us. I know, I know, we’re a growing community, collectively we outnumber a small denomination of Christianity, validation for everyone– but that’s my point. Collectively, there are more American “Wiccans and Pagans” than there are Presbyterians. The numbers for individual paths are much, much smaller– estimates for Heathenry, itself a category with a range of more granular identities, are at less than 20,000 worldwide. As a reminder, there are upwards of 7.5 billion people on this planet, and over 2 billion of them are Christians.

Remember that thing I mentioned earlier, about pack security? Yeah.

There’s no right way to be marginalized. You are not going to find the magic label that gives you access to the Forbidden Privilege Zone. Peeling your community apart so that you can throw out the sections you think are too weird or too different or that interfere with your respectability politics does not protect you, and it sows mistrust in the very community that you should be relying on. The semantics and history and quibbles aside, Pagan is a useful term– just as queer is– and it’s ours, we stole it, we turned it inside out. Use it. Turn your teeth on your enemies, not on your allies.

nagaP yhW

Pagan!

Ah, do we really have to use that word? It’s trouble.

Hail the givers! A guest has come

where shall he sit?

Hard pressed is he,

who tests his luck by the fire.

(Havamal [2], Chisholm.)