A couple weeks ago, Cyndi Brannen of the Keeping Her Keys blog asked “what is it that makes witchcraft… witchcraft?” Jason Mankey liked that idea so well he asked all the Patheos Pagan bloggers to write on what makes what we do what it is.

My first thought was to write on Druidry. It would be both easy and timely to write on polytheism. But after further thought I want to explore this question at its broadest level: Paganism. What is it that makes Paganism Pagan?

The origin of “Pagan”

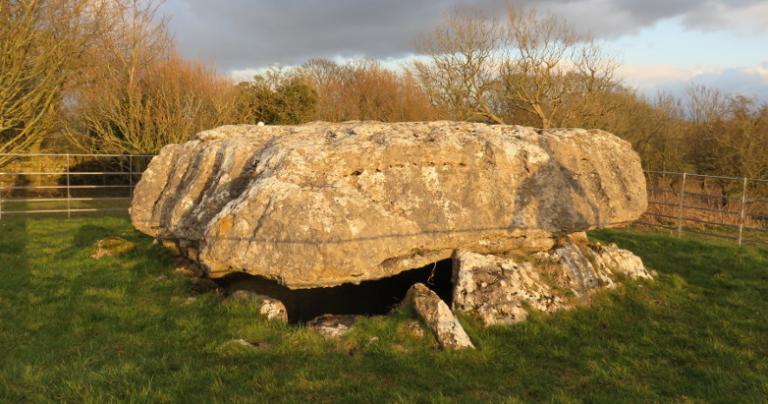

The English word “pagan” comes from the Latin word paganus, which means “country dweller.” It was used by the invading Romans as a term of derision (think “hick”) to refer to the native Britons who worshipped in sacred groves and wild places instead of in “proper” temples. When the Empire converted to Christianity, the term was used for those who kept their ancestral religions regardless of where they lived.

The term stuck. When all the English-speaking world became Christian, it was used to refer to anyone outside the Abrahamic tradition (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) – again, as a term of derision. It reached its worst during the days of the British Empire, when Imperial operatives, missionaries, and scholars lumped ancient Greeks, Celts, and Norse together with Hindus and Buddhists and with the remaining tribal religions of Africa and Asia.

What do all those diverse “Pagans” have in common? They weren’t proper civilized English-speaking Anglican Christians. That’s it. When you read “pagan” in 19th and 20th century literature, it almost always means “not us, and therefore wrong and in need of correction.”

No ancients called themselves Pagan

It’s not hard to imagine a conversation in southern Britain around 400 CE that went something like this. “Paganus? You’re damn right I’m paganus. Now get out of here before I go all Boudica on your Roman ass!” Terms of derision often become a badge of honor.

Other than that, though, no one ever called themselves Pagan. The Iceni were the Iceni. The Hellenes were the Hellenes. Religion wasn’t a set of beliefs to be affirmed or denied, it was part of who you are and especially whose you are.

We often speak of “ancient Paganism” but there is no such thing. There were many ancient religions, some of which were similar, some of which were syncretized (see Ptolemaic Egypt), and some of which have virtually nothing in common. It is a conceit of the modern West to assume that “deep down it’s all the same” when even a casual look at the foundations, core beliefs, and regular practices of different religions clearly show that they are, in fact, different.

And that, too, is part of our heritage.

Our more recent ancestors wanted to be Pagan

In his excellent survey of Pagan philosophy The Earth, The Gods and The Soul, Dr. Brendan Myers said:

People got tired of the austerities of Christian discipline and the misanthropy of the Doctrine of Original Sin. They maintained the appearance of being committed Christians, of course … But they dramatized for themselves a world that never knew Original Sin, and so still existed in a state of original blessing. In that imagined world it was no sin to ‘dance, sing, feast, make music, and love.’

The Europeans of the Renaissance and after didn’t know exactly what they were looking for, but they knew they wanted something that wasn’t proper civilized Anglican Christianity. And they had a word for it: Pagan.

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon,

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers,

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. –Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.“The World Is Too Much with Us” – William Wordsworth (1802)

Pagan or Neo-Pagan?

Expressing Pagan yearnings and Pagan themes in a Christian context is one thing. Abandoning Christianity for a Pagan religion is something entirely different. That started happening in significant numbers in the second half of the 20th century. And when it did, some people began to realize they weren’t doing anything like what the Paganus were doing 2000 years earlier.

Oberon Zell-Ravenheart is generally credited with coining the term “Neo-Pagan” to describe the Wiccan and Wiccan-influenced religions that were growing in popularity from the 1960s forward and that focused on reverence for Nature, gender equality, sexual freedom, and magical practice. It was an attempt to say “we’re reimagining ancient religions for our era.”

By the time I got here in 1993 “Neo-Pagan” was already fading. It doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. More than that, people began to understand that the Pagan movement was never going to be just one thing – it was going to be many things. There was Gardnerian Wicca, Alexandrian Wicca, and eclectic Wicca. There were several dozen forms of Druidry. Heathenry, Hellenism, Kemeticism, and countless other traditions were rising. We might – or might not – all call ourselves Pagans, but we knew that deep down we had some differences, and we saw no reason to ignore them.

Some people didn’t like this “speciation” and wanted unity, but at the cost of the distinctions that give our various traditions depth and meaning. In 2014 John Halstead tried to re-establish “Neo-Paganism” and set up a very nice website, but it doesn’t appear to have been updated since its launch, and the term is rarely used among practitioners.

Today we have Pagan music, Pagan books, and Pagan Pride Day. We wear Pagan jewelry and go to Pagan conferences. This website is called Patheos Pagan. I wrote a book called The Path of Paganism. Language is an organic thing that evolves on its own, and “Pagan” is the winner.

The Big Tent of Paganism

I first heard the phrase “Big Tent” in reference to the Democratic Party’s attempt to appeal to voters with a wide variety of interests: labor unions, racial minorities, feminists, LGBTQ persons, economic liberals, and more. It’s a place where groups who are too small to exert significant influence on their own can come together and use their collective power for the common good.

I wrote about the Big Tent of Paganism in 2015.

The Big Tent provides a visible, easy-to-find entry point for ordinary people who are looking for something their current religion isn’t providing. And it makes it much easier for us to find others inside the tent who are doing the same things for the same reasons …

We are not one. There is no single Pagan religion and I have no desire to create one. But the Big Tent of Paganism is a useful and beneficial approach to grow and support our many Pagan religions.

We understand that Wicca and Norse Reconstructionism aren’t the same things. We know that what modern Druids do probably isn’t all that close to what the ancient Druids did. And perhaps most importantly, we understand that while there is much we can learn from Hinduism, African Traditional Religions, and other remaining tribal religions, they are not part of the Pagan movement and they are not ours to take.

But where we can come together to support things like The Wild Hunt and Mystic South, and where we can raise our collective visibility far higher than we can individually, we are better off embracing the Big Tent of Paganism.

Pagan currents

And that brings us back to our original question: what is it that makes Paganism Pagan? The answer lies in all the complicated – and at times, conflicting – usages of this problematic word throughout the centuries.

It’s the beliefs and practices of our pre-Christian ancestors. It’s their values and virtues and ways of seeing the world. It’s their Gods. It’s what was stolen from us by missionaries and empires, and it calls us to reclaim our heritage.

It’s the organic religions of the world, which arise not from the word of a prophet (not that there’s anything wrong with prophets) but from the interactions of a group of people with the land and the spirits where they live. It calls us to put our faith in our lived experiences and the experiences of our co-religionists rather than in sacred texts or creeds that are frozen in time.

It’s living in a world that, despite its challenges and indifferences, is not fallen but good. It’s dealing with the thorns to enjoy the beauty of the rose… and then finding that the thorns are beautiful in their own way. It calls us to “dance, sing, feast, make music, and love” and to enjoy our time in this life as deeply as we can.

It’s the organic religions arising from the lived experiences of people in the industrial and post-industrial West. It’s a reverence for Nature and it’s seeing the Divine in all genders. It’s the magic of the learned scholars and the magic of the ordinary folk – the paganus of today. It calls us to remember that good religion is a living thing, growing and changing to adapt timeless principles to where we are here and now.

These four “currents” are what makes Paganism Pagan. Like currents in the ocean, they collide, combine, and comingle in ways that can be difficult to predict. Sometimes they are in conflict, and no one expression of Paganism can be all these things in full. This is why we cannot define Paganism, and why the best description of it uses a model with four centers.

Self-identification and the Big Tent

Some people who wander into the Big Tent of Paganism say “I’m not a Pagan.” They find their primary identity as a Heathen or a Hellenist, as an animist or a polytheist. So be it. A big part of religion is who you are and whose you are, and if you don’t identify as Pagan, I’m not going to call you a Pagan even if you spend a lot of time inside the Big Tent.

And even though I’m inspired and at times informed by the tribal religions of the world, I’m not going to insist that they’re Pagan. Their identity is their own and we have no right to claim them.

My primary religious identity is polytheist – the worship of the many Gods. But my polytheism is a Pagan polytheism – it flows from the Pagan currents, from the many ways in which the word paganus has morphed and evolved over the centuries.

This is what makes Paganism Pagan.

Addendum: In a Facebook comment, Dr. Edward Butler took issue with the common belief that “pagan” meant “country dweller.”

Edward Butler: Pagus is a district, not necessarily a rural one. We see its descendants in Romance languages such as French pays, which means a country or nation. I would argue that pagani, which as far as I know in its religious connotation originates with Christians, functions as a direct Latin translation for the Greek term ethnê, “nations”, which is used in the New Testament to refer to the “gentiles”, the faiths which are particular to some nation, as opposed to the new church, which is “catholic”, from Greek kath’holikos, “pertaining to the whole”, i.e., “universal”.

John Beckett: I think I hear you saying that “pagan” was still a way of othering people who kept to their ancestral religions, though not in the way most modern Pagans think. Is that a fair assessment?

Edward Butler: Yes, it was definitely a way of othering people by saying that they belonged to a religion that was “particular” instead of the one that was “universal”. That was the method of othering, not the charge of being “rustic”.

Another common term that early Christians used for pagans in the East was simply “Hellenes”, which was used even for people who were not ethnically Greek in the modern sense, but who were seen as upholding the values of Hellenistic civilization as it had developed over the centuries since Alexander, which included polytheism.

I say this because there is a tendency, greatly encouraged by Christians, to project the evils of Christianity as much as possible back onto the Roman Empire, as though what the Christians did in eradicating indigenous faiths was no more than what pagans had already been doing to one another, just “business as usual”.