Before the advent of modern science, no one knew the moon was 238,900 miles away or that traveling millions of light years was required to reach the stars.

The celestial bodies, it was commonly believed, were in the general neighborhood of Earth. About 900 years ago, Irish scribes wrote in the Saltair Na Rann that the earth was round like an apple and the stars were less than a thousand miles away. Across cultures and continents, people once believed the great rivers of earth were connected to the Milky Way.

• In Irish legend, the Milky Way goddess Boann walked three times around a mythic well that erupted in bright white water to create the Milky Way and the Boyne River in County Meath.

• In Hinduism, the river goddess Saraswati embodies the flow of water down the Milky Way, which turns to snow that falls on Mt. Meru and melts in spring to recharge the River Ganges.

• In China, the Milky Way was believed to connect with the “heavenly” and “starry” Yellow River in the west, and with deep springs under the vast ocean to the east.

• The Barasana of northern Colombia see the Milky Way as a cosmic waterfall on the eastern horizon, sending precious water that flows down the mountains, recharging the Amazon River.

• The modern descendants of the Inca believe that after the Vilcanota River runs through Cusco, the oldest city in the Americas, it joins up with the Milky Way on the horizon.

• In ancient Egypt the Milky Way goddesses Hathor and Isis were associated with the rising of certain stars in June, coinciding with the Nile’s annual flooding.

Cultures around the world once believed that sacred waterfowl carried human souls on a migratory journey along the Milky Way. In Scandinavia, the Baltic States, Central Asia, Siberia and North America the Milky Way was known as “the path of birds,” specifically for migratory waterfowl such as ducks, geese, swans and cranes. The same cultures also knew the Milky Way as the “route of dead souls.” If the Milky Way was a cosmic migratory flyway, what was the destination? Where was the wintering ground?

The heavenly celestial pole

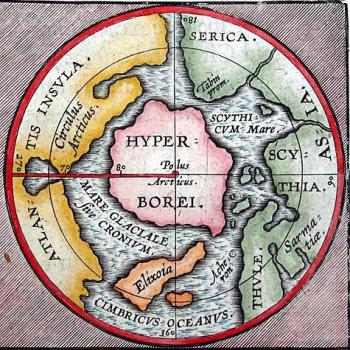

Each hemisphere has its own celestial pole – both are visual illusions created by the spinning Earth, making it appear that all the stars circle around a single point, the hub of the universe. The 6th century druid poet Taliesin described the northern celestial pole as “the pin of pivotal space” where a glittering palace constantly turned.

A pole or tree was imagined to extend upward from a sacred site on earth to fit into the cosmic hub like the handle of a twirling umbrella, wielding the power to stir the cauldron of stars, space and time. Across cultures the celestial pole has been described as a fountain, the navel of the universe, a whirlpool, a cauldron, a glittering palace, a celestial mill, the sky nail, Vishnu’s Toe, and Buddha’s Nandana Grove.

In recent millennia, when Polaris was closest to the celestial pole, most Native American tribes called it the “Star That Does Not Move,” or the “Not-Walking Star.” Yet some also identified Polaris as an immortal deity commanding the sky that turned around it.

The Luiseno and Maricopa of southern California called Polaris “Sky Chief” and “Captain” respectively, while the Pomo of Northern California called it “The Eye of the Creator.” Originally from the flat landscapes of Nebraska and Kansas, the Pawnee saw Polaris as the supreme being Tirawa, chief of all stars. Tirawa was the One Above, changeless, and supreme, the one who originally placed all the stars carefully and deliberately in the sky, then sprinkled the heavens with a band of crystal chips to form the Milky Way.

Migrating souls

Perhaps the most literal description of the soul’s afterlife journey to the heavenly celestial pole is found in the Finnish epic Kalevela, which describes swans flying souls of the dead to a warm place beyond the horizon, and then up the Milky Way, known as Linnunrata or Path of the Birds.

As the soul-bearing swans approach the northern celestial pole, a swirling wind caused by the turning bowl of the sky pulls them out through a small hole to a heavenly land of rest called Tuonela. Ultimately the swans complete their round-trip migration and return the healed and rejuvenated ‘new’ souls to pregnant mothers on Earth. A similar Ukrainian legend describes birds spending winters in heaven and returning in spring with eggs.

The Finns’ notion of soul flight to the celestial pole may stem from their observation of whooper swans migrating southeast in late fall, heading toward a point where the distant horizon met the Milky Way. In the imagination of those who forged the myth, the swans flew beyond the horizon of the material world and into the spirit world of the Milky Way, where Cygnus the swan could be seen flying north towards the celestial pole.

The Finns may have observed that the smattering of red neck feathers on the earthly whooper swan seemed to match the orange and red tinges of some of the stars that make up Cygnus. During the cold months of winter, Cygnus appears to fly up and around the pole, as if tending a nest.

As spring arrives, Cygnus appears to dive toward earth again. In Norse myth, unborn souls wait in the Fountain of Urd (a stand-in for the celestial pole) to be gathered by storks, which deliver souls to the wombs of expectant mothers. Slavic cultures also believed the stork delivered human infants. In Hawaii, the frigate bird is believed to return babies from heaven. A tradition on the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia is for an expectant mother to eat a bird at the base of a sacred tree just before delivering her child, or the soul will not be joined to the infant.

The Divinity of Turning

In the Hindu legend, “The Churning of the Ocean of Milk,” weary gods returning from battle used a mythic snake to turn a polar mountain, causing the stars to rotate faster and faster until they bestowed gifts, including a physician, a gem for Vishnu, a flying elephant for Indra, the pipal (fig) tree, the coconut palm tree and finally Surabhi, a cow with a woman’s head that provided a healing elixir of cosmic milk.

The mythic snake that spun the celestial pole likely represented the Draco constellation, which is always visible turning closest around the northern celestial pole. In ancient Greece, the Rod of Asclepius depicted a snake turning around a pole, symbolizing healing and medicine. The Greek Bowl of Hygieia showed a snake turning around a bowl or chalice, symbolizing pharmaceutical medicine. The cosmic turning action is also found in the Japanese creation story, which describes a divine couple standing on a celestial bridge and using long poles to stir the primordial mass of earth, forming the first island of Japan. The couple then descended to the island and built a palace with a large pillar which they circled around to procreate and form the other islands, gods, and creatures.

In ancient China, a legend described the emperor being infused with divinity when the pole star shined its light on his mother as she gave birth to him. Later in Chinese history, Confucius taught that the economy revolved around the emperor just as circumpolar stars turn around the celestial pole. The physical layout of ancient Chinese cities lined up with various constellations, with the emperor’s palace at the center, representing the pole.

Similarly in Nebraska, the Skidi Pawnee established villages that aligned with their constellations, each of which carried a spiritual meaning. As the constellations rose and set through the seasons, a ceremony was held in every corresponding village. The annual cycle of rolling rituals began in spring with the “First Thunder” ceremony, held in the village symbolizing Tirawa, the supreme being identified with the celestial pole.

The Navajo name for the pole and the circumpolar stars turning closely around it is nahookos, meaning to turn. The Navajo perceived a celestial father and mother circling around Polaris, known as the Central Fire, a celestial match for the fireplace in the family Hogan. The cosmic father is a chief and a warrior while the mother turns a grinding stone and stirring stick to provide nourishment.

(Ben H. Gagnon is the author of Church of Birds: an eco-history of myth and religion, just released on April 1 from John Hunt Publishing in London; now available to order here and through other booksellers. More information can be found at this website, including a link to a pair of videos on the book on YouTube.)