Beginning about 12,000 years ago, the intentional shaping of the human head known as cranial deformation may have been an attempt to reproduce the egg-shaped skulls of Neanderthals and channel their ancient wisdom through sympathetic magic.

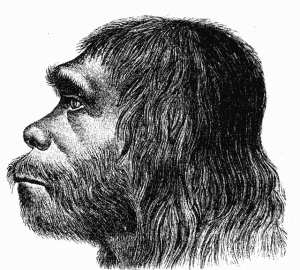

For more than a century western scholars were dead wrong about Neanderthals, speculating that modern humans had superior brain power and either killed them off or took control of food resources. Coincidentally, this dark theory emerged when European colonists were killing off and otherwise oppressing indigenous people around the world, people they believed to be inferior. It appears that scholars of the time assumed the same dynamic must have been at work in the human-Neanderthal relationship.

But that’s not how it happened. Not even close.

Love and tolerance between sub-species

It may take some time to replace the popular belief that modern humans wiped out the stupid Neanderthals with something resembling the truth. The fact is humans and Neanderthals lived together over thousands of years in the Near East, Europe and Central Asia, almost certainly shared early religious beliefs, had sexual intercourse a lot, established ancestral cemeteries and shared burial practices.

Recent discoveries at Nesher Ramla in Israel – just north of Jerusalem – revealed a village of Neanderthal and archaic human hybrids thriving between 140,000 and 120,000 years ago. Its settlers had “a distinctive combination of Neanderthal and archaic (human) features,” according to a Tel Aviv University study published in the June 2021 issue of Science. Separate genetic studies have shown interbreeding occurred routinely in Europe and Central Asia between 80,000 and 50,000 years ago.

But the clinical term ‘interbreeding’ doesn’t capture the full picture. Modern humans and Neanderthals got along famously for more than 30,000 years. Although European DNA is about two percent Neanderthal, everyone has different bits and pieces – about half of the Neanderthal genome is still circulating, according to the Max Planck Institute.

Despite clear differences in physical appearance, two sub-species of Homo sapiens demonstrated the kind of tolerance and love toward each other that’s not always the case across races and ethnic groups today. We might not only learn a lesson from our ancestors about love and tolerance, we should also thank them. Without the Neanderthal DNA that complements our own, the human race would not be nearly as robust. We may not have survived either.

Did human disease cause Neanderthal extinction?

In the context of two human sub-species getting along so well it should be no surprise that humans carrying herpes from Africa to Europe about 50,000 years ago may finally answer the question of what doomed the Neanderthals. A 2016 study by the University of Cambridge published in the American Journal of Anthropology concluded that humans from Africa brought tapeworms, tuberculosis, stomach ulcers and herpes to Europe, likely contributing to the Neanderthal extinction.

The introduction of new diseases to populations without immunological defenses has occurred throughout history more often than we’ll ever know. Although complete records don’t exist, it’s estimated that at least 25 percent and possibly half of the Native American population died from diseases such as smallpox, measles and flu introduced by Europeans.

The contributing factors behind the extinction of Neanderthals have been debated for more than a century, but an equally interesting question has been overlooked: the impact on the survivors. How did our modern human ancestors react to the extinction of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis?

Mourning the Neanderthal

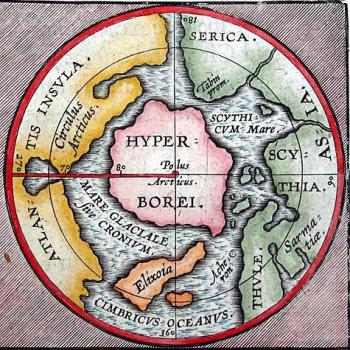

The archaeological evidence shows that after the extinction, humans settled in the same active volcanic areas where Neanderthals had lived and built shelters in the shape of an egg, the same shape believed to be used by Neanderthals about 400,000 years ago near modern-day Nice.

Modern humans also continued to build egg-shaped stone rings, as Neanderthals did 175,000 years ago deep inside Bruniquel Cave, also in southern France. Archaeologists have determined that the symbolic use of flight feathers and talons taken from vultures and raptors began with Neanderthals, a practice that continues to this day in some indigenous cultures.

Both modern humans and Neanderthals established ancestral graveyards, decorated skulls, buried red deer bones with the dead, used ocher as a red pigment, made tools from obsidian and necklaces from seashells. Continuing the traditions of Neanderthals suggests humans identified closely with their departed cousins. The extinction may have been viewed as a tragedy that was widely mourned.

Quickly following the Neanderthal extinction, the Gravettian culture emerged more than 30,000 years ago across Europe, including the same volcanic regions of Germany, France and Spain where Neanderthals had flourished. The egg shape was common in Gravettian settlements at Predmost and Dolni Vestonice, Moravia, including oval homes, an elliptical burial pit, and figurines of the “Venus” mother goddess with over-sized egg-shaped hips and bellies.

Other figurines created at the time across Eurasia included a category of bird-women, often with a bird head, a beak and a female body. Between 24,000 and 29,000 years ago, the Pavlovian culture built egg-shaped houses in mountain valleys between southern Poland and Austria.

In 2002, a study released by the Instituto Português de Arqueologia described the burial of a four-year-old human with red deer bones about 24,500 years ago at Lagar Velho, a rock-shelter near the northwest coast of Portugal.

About 70,000 years earlier and 2,500 miles away at Qafzeh Cave in Israel, Neanderthals buried the antlers of a red deer on the chest of a 13-year-old child. At nearby Amud Cave on the Sea of Galilee a Neanderthal infant was buried between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago with the jawbone of a red deer resting on its pelvis.

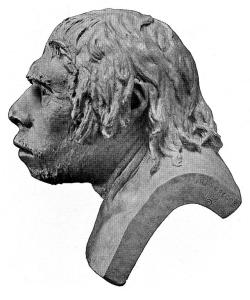

Neanderthal skulls and cranial deformation

The archaeological record shows cranial deformation began 12,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Near East, China and southeast Australia, coinciding with the chaotic effects of post-Ice Age climate change. Over time, intentionally shaping the heads of infants became a worldwide phenomenon found in Africa, Europe, Asia, Australia and the Americas.

Forensic head reconstructions by French artist Elisabeth Daynès showed that head shaping was practiced in ancient Egypt, but only by the controversial pharaoh Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their three children.

Most scholars believe the purpose of elongated skulls was to identify people belonging to families of high status. A 2018 study at Charité University Medicine Berlin found that elongated heads were a clear marker separating Peruvian elites from the rest of the population. The study suggested that in times of regional conflict in Peru’s Colca Valley, efforts to negotiate were facilitated by the fact that elite groups on all sides had oval-shaped heads, establishing a common ground.

Other studies have shown that cranial deformation among elite groups tends to coincide with greater social control, partly through the visual reinforcement of separate and distinct identities and associated societal roles. While scholars have studied a range of physical methods once used to shape the cranium and the possible societal implications, the significance of the shape itself seems to be overlooked. The product of cranial deformation was typically an egg-shaped oval, the same shape as a Neanderthal or Homo erectus skull.

A reactionary response to climate change?

Because modern humans (with round skulls) inhabited Neanderthal settlements after their extinction and practiced similar burial rituals, they certainly had ample opportunity to find the egg-shaped skulls of their distant ancestors. Intentionally deformed human skulls were found in northern Iraq at Shanidar Cave, which is also a Neanderthal burial site. Deformed egg-shaped human skulls were also found in China’s Zoukhoudian Cave, where the remains of Homo erectus pekinensis had been buried eons before.

When the first evidence of cranial deformation appeared between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago, people were living through a chaotic climatic period in which glaciers were melting, temperatures were shifting wildly and normally predictable food sources were disrupted. Many scholars believe farming developed in response to the dislocated food chain.

In times of chaos and rapid change, cultures often take a reactionary turn to the past and embrace old and trusted traditions. At a time when people believed the soul resided in the head, perhaps cranial deformation was an attempt to reproduce the egg shape of the Neanderthal skull. In the language of sympathetic magic, the egg-shaped skull would serve as a vessel to attract the souls of long-dead Neanderthals, bringing ancient wisdom to an unpredictable world. Just as any priest in any religion wears some kind of identifying marker, the artificially oval head may have been the visible mark of a priest or priestess who channeled Neanderthal wisdom.

While there’s no evidence that Neanderthals made it to Australia, remains have been found on the Melanesian Islands off the northeast coast. Meanwhile, genetic analysis has shown the ancestors of Australian Aboriginals, who practiced cranial deformation almost 12,000 years ago, may have mated with an unknown human-like species in the distant past, according to a 2016 study published in Nature.

(Ben H. Gagnon is the author of Church of Birds: an eco-history of myth and religion, just released on March 31 from John Hunt Publishing in London; now available to order here and through other booksellers. More information can be found at this website, including a link to a pair of videos on the book posted on YouTube. The latest video is “Nazca Lines intended for migratory birds, not UFOs.”)