Super-Kings With Special Substance

Imagine that we could grab a sample of typical citizens off the streets of various civilizations throughout history, from the Sumerians to today, and quiz them about ontology — the branch of philosophy that studies existence. I think we would get a naive sort of realism. This brick? It exists, our subject replies, what a stupid question. The unicorn that the town drunk said he saw behind the tavern? It does not exist, it’s a fiction or a delusion or a lie. A good story, though, the bit about that unicorn and the blacksmith’s daughter is true even if it’s not, you know, “factual”. The number three? It exists — see, I have three coins in my pocket. (You think I can’t count or something?) People like you and me? Of course we exist, we’re standing here talking to each other.

And if we also asked them about theology, if we asked them to describe the primary deity of their culture’s pantheon, I think the picture that would emerge is that of a king but even moreso — a super-king, a magic king. Indeed, in some cultures a king could be promoted to godhood.

The idea of kings is central to the hierarchical social structure that has been with us since we became farmers and city-dwellers. Every citizen controls some bit of land, from the peasant’s plot to the lord’s realm; and each man has power over some number of people, from the head of the peasant household ruling his wife and children to the chief of the whole nation. The kings are the ones on the top of their various heaps, the ones who rule the most land and the most people.

And even though I’m a Zenarchist who looks forward to Universal Enlightenment and the subsequent abolition of the state, I have to acknowledge that a lot of people find that hierarchy very comforting. Someone is in charge. People can know their place in the social order.

But why stop there? It’s an obvious extrapolation to follow that curve upward: there must be a ruler of the whole world and everything we see, the sun and the moon and the sea and the rains. It would take power far beyond what any mortal has to rule all that. Magic power. And this ruler would have a royal court, of course. There’s your head deity and your pantheon.

And that heavenly king is comforting to a lot of people too. There is not just a social order but a cosmological order. God is in his heaven and all’s right with the world.

Even most citizens of the nominally democratic United States believe in the heavenly King of Kings — and we’ll leave for another time the problematic implications of spiritual monarchy in a democracy. (The Athenians at least had Zeus’s kingship of the gods be subject to limitations.)

The point I want to emphasize here is that there is a common and unsophisticated notion of deity which I think at least in part comes from projecting hierarchical social structure upwards. As below, so above.

And it’s worth pointing out that only as that agricultural social structure has started to fall apart the past few centuries — starting with the humanism of the Renaissance and moving through the birth of modern science in the Enlightenment and the whole-scale social change of the Industrial Revolution — has atheism been able to find any sort of social opening. It would be interesting to trace the parallels between the rise of philosophical atheism and the rise of philosophical anarchism. Maybe as we’re figuring out that we don’t need kings on earth, we don’t need them in heaven. Again, as below, so above.

Put this “common sense” ideas of deities and of existence together you get the gods — and goddesses, but let’s be honest, the power dynamic in religion has historically been as sexist as it is in politics — as super-powered super-royalty. Kings (and Queens) and Princes of the Universe, Lords (and Ladies) of All, possessed of the power to bend and shape the world to their liking, as real and as independent of human beings as bricks are (at least according to our common sense), but made of a more rarefied sort of substance not subject to the constraints of normal matter.

Under that set of definitions, I confidently assert that reason leads us to conclude that no gods exist, that they are like the town drunk’s unicorn: fiction, delusion, or lies, perhaps useful as metaphors, but not real. Not only that, but not being a big fan of kings I’m downright glad to say that no such gods exist. Ha! I thumb my nose at the empty heavens!

But these are not the only notions of “realness” or of deity out there.

I want to look at some alternative ideas, but I want to be clear that I’m just pointing out a vast range of possibilities, not claiming that I have the True Understanding of the nature of existence and of the gods. (Not yet, at least.)

What Does It Mean to Exist? Anatman…

Existence is a weirder thing than we think of in our day-to-day life. Let’s consider for a moment the existence of a subject near and dear to my heart: me. According to the teachings of Buddhism, in a sense I do not exist.

I don’t mean that there’s some conspiracy to present a fake author, or that everything we experience is a dream or a simulation a la The Matrix. The teaching called anatman (Sanskrit) or anatta (the Pali equivalent) says: okay, your physical body exists, you have emotional reactions and senses like sight and hearing and touch and time, and you perceive the world and you have memory and intellect. But nowhere in these piles of stuff, these skandhas, is there a self that’s separate from it all, an atman.[Keown, 734-738; Hahn, 9] If you take me apart there’s no self in there, any more than if you disassemble an old style mechanical watch you’ll find the “watchness” in there somewhere.

The “watchness” of the watch exists only as a relationship of the pieces and of the external world — mostly the owner who keeps winding it and uses it to tell time, but also the watchmaker, the owner’s wife who gave it to him as a gift, and so on. The “me-ness” of the thing we call by convention “Tom Swiss” exists only as a relationship of the pieces — body, memories, perceptions — and of the world, both physical and social. “Dependent arising”, as the Buddhists say.

“I” exist only as a set of relationships that includes the food I eat, the air I breathe, the sunlight that powers the photosynthesis that makes all that possible; and also all the other humans with whom I participate in the social interaction that makes thought possible. (No interaction, no language; no language, no thought as we usually understand it.) The Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hahn often speaks of “interbeing”.[Hahn, 3]

It’s like the punchline of a famous Mullah Nasrudin story: “I am here because of you, and you are here because of me.”[Shah,2]

If “my” existence is so conditional on the world around me and on other people…what should we expect about the deities?

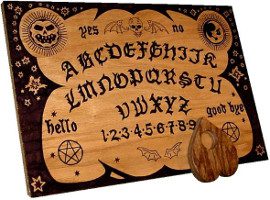

…and the Ouija Board

And if that’s a puzzler, consider for a moment the Ouija board. Or any sort of automatic writing controlled by more than one person at the same time, but Charles Kennard’s good old “talking board” (a brand originally made in Baltimore,[McRobbie] hometown pride) is probably familiar to American Pagan readers. Odds are good that you played around with one a little when you were a kid, or at least knew someone who did.

If you’re using a Ouija board solo and holding a conversation with some sort of Other, from a skeptical perspective it’s easy to say that the Other is an aspect of your own subconscious mind, that you’ve worked yourself into a disassociative state. It’s weird and tells us some interesting things about the mind, but doesn’t bring up any ontological issues.

But if you’ve ever experimented with using one with a partner (or several people, a Ouija-a-trois) and you’ve been able to have some sort of sensible conservation with some sort of something…what was it?

If, as skeptical atheist types, we discount supernatural disembodied spirits, and if we assume our fellow Ouijaers weren’t engaged in some conspiracy to fool us, what was on the other end of the line? It seems that these conversations were held with a mind whose physical correlate was not a single brain, but a shifting collection of the neurons of two or more brains, linked not only by the usual synapses but by non-conscious verbal and non-verbal communication between the people holding the planchette. A weak sort of group mind — “weak” in the sense of not absorbing the participants. Not a mob, not a Borg.

I don’t mean that this “group mind” is anything supernatural or paranormal or telepathic, just more subtle than we usually encounter.

So, consider: what sort of weak group minds might arise in the subconscious minds of an entire society over a long time? Could the right sort of ritual function as a talking board to let them communicate?