Of all the lines that divide the modern pagan community none may be so sharply defined as hexing. To some it is an absolute moral issue; to others a matter of pragmatism. On this issue at least there seems to be very little room for negotiations between the two.

For this article I am using hexing and cursing synonymously and using the dictionary definition of cursing: to use magic or invoke a supernatural power to inflict harm or punishment on someone.

I think, as someone who studies the art of cursing and is willing to use it when necessary, that there are a lot of misunderstandings about both what hexing is and about people who hex. Not that its entirely surprising — we live in a culture after all that’s soaked in stereotypes of the evil witch offering the poisoned apple, cursing out of jealousy and pettiness. Even people who have largely rejected the cultural tropes attached to the fairy tale witch seem to have a hard time letting go of that one, and tend to hold on to the idea that if someone hexes they must be, somehow, a bad, dangerous person who just enjoys hurting other people. Naturally there are people who do misuse hexing, who make it a weapon for bullying and intimidating other people, but the same is true for any kind of magic if its done with ill-will and bad intentions. Even blessings can be twisted to cause harm if the spirit they are said in is rooted in negative intent, and a healing can be used to hurt if it goes directly against a person’s own will or what may be best for their body.

Cursing is a powerful tool, and it can be dangerous if misused, however it can also be effective and useful; like martial skill some people may decide that pacifism is their preferred approach but others will choose to train in a form of fighting so that if its ever needed they have the skill. And like physical fighting hexing (all magic really) requires training, knowledge, and discernment to use properly. Actions have consequences and magic has repercussions; if done well a curse will not, in my experience, effect or rebound on the caster but it is something that requires care and precision to do safely. Also like martial skill, just knowing how to fight, or being willing to, or even having the experience of having done it, doesn’t make one a bad person.

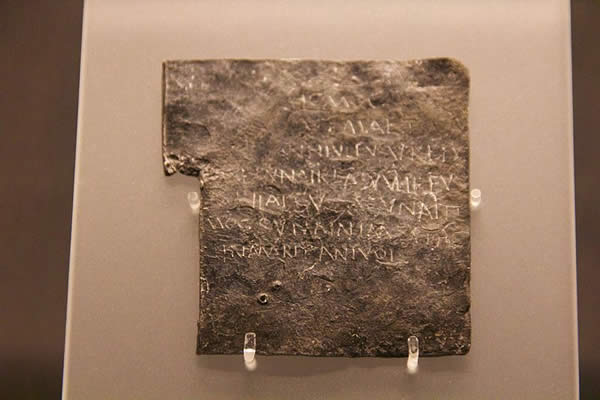

Hexing has a very long and very complex history behind it. I can only speak to the Irish and Celtic — and a bit of the Norse — history, as that’s my focus but I’d expect it to be similar in other areas. Archaeological evidence of hexing has been found in the form of ‘defixiones’ or curse tablets which are usually thin lead pieces inscribed with detailed writing including the person’s name, spirits or Gods being called on, why the curse is being laid, and what exactly it is supposed to do. Interestingly a large number of such tablets have been found at the healing springs in Bath England, a shrine once dedicated to the goddess Sulis-Minerva, and in these the curse was usually being requested due to theft of clothing (keep in mind the value and cost of clothing at the time). In the Scottish witchcraft trials we see examples of witches confessing to cursing others over slights or offenses they otherwise had no means to address due to their own social station. In the Carmina Gadelica cursing is referenced in the form of malediction as a means to punish those who are stingy or offensive to guests.

From a mythological point of view we do see cursing purely as a plot device of course, but we also see it in stories and folklore with the same weight it has in some actual human use. The Good People (aka fairies) have long been reputed to curse people in a variety of ways as punishment for transgressions including breaking the social order between humans and the Fey or damaging property belonging to Themselves. Trying to cut down a fairy tree, for example, is known to bring on a curse by the Other Crowd in Ireland and moving a fairy boulder earns the same result from the alfar in Iceland. In the Norse we can look at Egil’s Saga and see the example of the hero Egil using a curse against the king and queen who outlawed him, or in the story “The Curse of Busla” a curse is used to force the king to spare the life of Busla’s son who was condemned to death. In Irish mythology the goddess Macha curses the men of Ulster after they force her to race against the king’s horses while she is heavily pregnant and in labor, giving to them all the same pain she has experienced for nine full days when they are in the most need of their own physical strength and health. The fairy queen Aine curses the mortal king who raped her, stripping him of everything of value from his crown to his wealth.

Cursing then has been and can — I’d argue should — be used as a means for the disempowered and socially disadvantaged to level the playing field. When a person — a witch or other magic user — has been wronged or harmed in some way and has no other option to obtain justice, or if they feel that there is a need for justice or reparations on a wider scale they may choose to use magic as a means to effect the desired outcome. Obviously this will always come down to perspective and a matter of personal ethics, deciding for one’s self what is and is not justified. Although I don’t personally agree with all of the modern examples that have been making the rounds recently, we can at least point to them as examples — the movements to hex rapists given light sentences by lenient judges, the joint effort to use curse-work to stop the pro-rape men’s Meetup groups movement worldwide; the use of virtual nidstangs (Norse curse poles). All of these in their own ways were people who felt powerless in a situation using cursing to try to reclaim control and effect an outcome that favored them or that they felt was just.

I’ve seen people suggest that cursing is wrong because it effects the free will of other people, but when we get down to it almost all magic does. A spell to help me get a job or buy a home must, by nature, effect other people because lining things up in my favor will most likely mean making them less favorable for someone else. A healing spell for someone else done without their knowledge — something I see pretty regularly mentioned online — is ultimately no different ethically than a curse; it is the subversion of someone else’s energy and intent without their consent. And lets be clear, unless someone specifically and explicitly tells you they want you to do such a spell for them then they haven’t consented to it and may not want it or realize you are doing it. I will say though that just like any positive magic you should never do any hexing without full awareness that it will have consequences, both to the person you are focusing on and potentially to yourself. What I usually tell people is that if you aren’t willing to physically hit someone, then don’t magically hit them either.

Some will argue that cursing has no place in the world today, and I respect everyone’s right to make their own choices. For myself though, as long as the world is a place of disparity, as long as life is inherently unfair, as long as some people have power and others do not and that power can and is used to victimize people, then cursing will have its place. Cursing, to me, is a tool like any other, a means to accomplish an end and if I feel that end is justified and necessary and worth the effort to work the magic then I may be willing to do it. It should not be undertaken lightly, but then again no magic should. All magic has consequences, and all magic has a cost that we must be willing to pay, whether our goal is positive or negative by society’s standards.

Patheos Pagan on Facebook.

the Agora on Facebook

Irish-American Witchcraft is published bi-monthly on Tuesdays here on the Agora. Subscribe via RSS or e-mail!

Please use the links to the right to keep on top of activities here on the Agora as well as across the entire Patheos Pagan channel.