1.

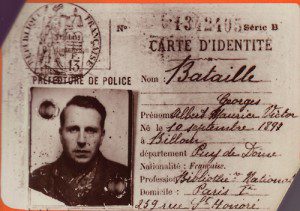

In his essay “Base Materialism and Gnosticism,” French philosopher Georges Bataille extols the potential value of a kind of Averse Gnosticism — a Gnosticism in which the demiurge of the material world, considered by the ancient Gnostics to be the “chief guard” of the prison of matter, and therefore a malevolent being, is in fact the object of worship and devotion. As Bataille explains, “the adoration of an ass-headed god” — one of the ancient images of the Gnostic demiurge — “seems to me capable of taking on even today a crucial value: the severed ass’s head of the acephalic personification of the sun undoubtably represents, even if imperfectly, one of materialism’s most virulent manifestations” (Visions of Excess, 45).

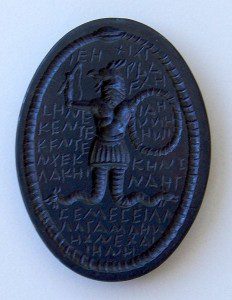

Bataille’s early twentieth century understanding of Gnosticism leaves much to be desired, academically speaking. He was not an expert in Gnostic doctrines, and lacked the primary source texts we today have access to when attempting to assess Gnostic ideas. He essentially admits as much when he suggests that “the protean character” of Gnosticism “has given rise to contradictory interpretations” (45). Bataille’s opinions about the ancient Gnostics comes mainly from his analysis of Gnostic talismans and jewels, which, according to Bataille, “precisely confirm the bad opinion of the heresiologists” (46).

This “bad opinion” is that the Gnostics espoused a “disfigured,” but “profound” dualism, reminiscent more of Manicheanism than Neoplatonism or Christianity. Bataille writes, “it is possible to see as a leitmotiv of Gnosticism the conception of matter as an active principle having its own eternal autonomous existence as darkness (which would not simply be the absence of good, but a creative action)” (46). This would put Gnosticism at odds with ancient Hellenistic conceptions, which saw matter and evil as “degradations of superior principles” (46). Bataille’s Gnostics were the evangelists of a monstrous and terrifying creed:

Attributing the creation of the earth, where our repugnant and derisory agitation takes place, to a horrible and perfectly illegitimate principle evidently implies, from the point of view of the Greek intellectual construction, a nauseating, inadmissible pessimism … if we confine ourselves to the specific meaning of Gnosticism, indicated both by heresiological controversies and by carvings on stones, the despotic and bestial obsession with outlawed and evil forces seems irrefutable, as much in its metaphysical speculation as in its mythological nightmare. (47-48)

It is insignificant for Bataille that the ancient Gnostics rejected the “horrible and perfectly illegitimate principle” of the demiurge as a false god of materiality who wrongly believed himself to be the one true High God of the universe — sometimes figured as the Yahweh of the Old Testament. For Bataille, it is enough that the Gnostics, in his estimation, allowed matter and metaphysical “evil” an active role, as a creative force which cannot be reduced to a higher idealism or held at bay with abstract or rational forms. Base matter, for Bataille, is like a virus; it spreads and infects, and reformulates itself into newer, more virulent forms whenever we try to subsume it under the dominion of “higher values” like philosophical reason.

Bataille is interested in Gnosticism because the Gnostic demiurge, represented in ancient magical talismans through monstrous, bestial forms like the acephalic deity Ialdabaoth, are the perfect god-forms for his understanding of base matter — “the representation of forms in which it is possible to see the image of this base matter that alone, by its incongruity and by an overwhelming lack of respect, permits the intellect to escape from the constraints of idealism” (51).

Unlike the late antique Gnostics, who sought to escape from the prison of matter and its evil creator god through either a radical asceticism or a radical libertinism, Bataille’s valorization of base matter leads him to support, at least mythopoetically, the worship of a demiurgic deity of “intransigent materialism.” Bataille argues for an Averse Gnosticism whose adherents, ontological terrorists at odds with most religious traditions from antiquity to the present, support the anarchic supremacy of matter over spirit:

For it is a question above all of not submitting oneself, and with oneself one’s reason, to whatever is more elevated, to whatever can give a borrowed authority to the being that I am, and to the reason that arms this being. This being and its reason can in fact only submit to what is lower, to what can never serve in any case to ape a given authority … Base matter is external and foreign to ideal human aspirations, and it refuses to allow itself to be reduced to the great ontological machines resulting from these aspirations. (48)

2.

Has there ever been a religious tradition that actually adheres to an Averse Gnostic doctrine like that espoused by Bataille? The philosopher suggests that the Gnostics manifest “above all a sinister love of darkness, a monstrous taste for obscene and lawless archontes” (48). It is especially the existence of “a sect of licentious Gnostics and of certain sexual rites” which “fulfills this obscure demand for a baseness that would not be reducible, which would be owed the most indecent respect” (48). In the modern era, he locates a similar doctrine in the practices of occultism, suggesting that “black magic has continued this tradition to the present day.”

Of course, Bataille is somewhat overreaching in his suggestion that modern occultists fulfill the role of Averse Gnostics, devotees of a monstrous material deity of virulent base matter. Many modern occultists identify with Gnosticism, especially of the “licentious” variety, but few occultists valorize the supremacy of matter over spirit, or a hard dualism between matter and spirit. Occultists prior to the twentieth century predominantly agreed with the ancient Gnostics, suggesting that matter was a prison for spirits that contained divine sparks that must be freed, or with Neoplatonists who argued that matter is not evil, but certainly lesser in the celestial hierarchy than spirit.

In the twentieth century, the influx of ideas from Eastern traditions like Hinduism and Buddhism led figures like Aleister Crowley to suggest that matter was in some sense illusory, or at most a kind of “veil” clouding our perception of our perfect, spiritual selves. In Crowley’s commentary on Liber AL I.8 — “The Khabs is in the Khu, not the Khu in the Khabs” — he writes that

We are not to regard ourselves as base beings, without whose sphere is Light or “God”. Our minds and bodies are veils of the Light within. The uninitiate is a “Dark Star”, and the Great Work for him is to make his veils transparent by ‘purifying’ them. This ‘purification’ is really ‘simplification’; it is not that the veil is dirty, but that the complexity of its folds makes it opaque. The Great Work therefore consists principally in the solution of complexes. Everything in itself is perfect, but when things are muddled, they become ‘evil’. … I think that we are warned against the idea of a Pleroma, a flame of which we are Sparks, and to which we return when we ‘attain’. That would indeed be to make the whole curse of separate existence ridiculous, a senseless and inexcusable folly. It would throw us back on the dilemma of Manichaeism. The idea of incarnations “perfecting” a thing originally perfect by definition is imbecile. The only sane solution is as given previously, to suppose that the Perfect enjoys experience of (apparent) Imperfection.

Although he sometimes identifies as a modern Gnostic, Crowley flatly rejects the dualism of the ancient Gnostics. Rather than being spiritual beings trapped in the baseness of matter, who must free their divine sparks to rejoin the fullness of the Pleroma, we are already the Perfect. Our problem is simply the opacity of our material and mental veils; thus, our Great Work is to make our veils transparent through purification, so we can again see the Perfection that already lies within us.

As we can see, Crowley has more in common with an Eastern mystic than an ancient Gnostic, either of the traditional or averse variety. Many modern occultists follow in Crowley’s footsteps here.

3.

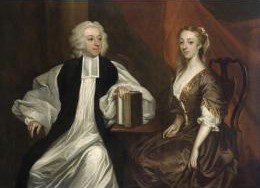

The eighteenth century Irish cleric and heretical theologian Robert Clayton provides an alternative. Clayton was a neo-Arian — his theology argued that Jesus Christ was not divine, of one substance with God the Father, but a lesser, created deity, the first-born of creation but not God godself. Yet Clayton arrives at this conclusion by articulating a deeply spiritist conception of the cosmos, in which all material creation is animated by spiritual beings. Thomas Duddy summaries Clayton’s position thus:

All nature … seems to him to be pervasively and permanently animated, the whole world ‘replete with Spirits formed with different Kinds and Degrees of Abilities, according to the various Ends and Uses, for which they were designed by their Creator’ … All created spirits are associated with particular forms of matter, and are, as it were, clothed in a particular set of material ‘organs’ through which they operate on the world. (Duddy, A History of Irish Thought, 120-121)

Some of these spirits are of such subtlety that they possess “bodies of so delicate a texture that they are in effect clothed in light, and ‘may make the Clouds their Chariots, and walk upon the Wings of the Wind'” — in other words, angels, who are spiritual beings of subtle bodies but nonetheless are still linked to materiality, as Clayton denies the possibility of any created thing that is not associated with some form of matter.

In Clayton’s spiritist doctrine, then, “Christ, as a being of spirit and flesh, is a being distinct from God, and cannot therefore be divine.” As Duddy explains,

Clayton’s position echoes that of the Arians, and his extraordinary vision of a universally animated nature is indeed intended to provide the metaphysical basis for his rejection of the doctrine of consubstantiality. Just as angels and other spirits are separate from God, so was Christ; just as they are sent by God, so was Christ … Clayton’s universal animism is intended to show that there are spirits active everywhere in nature but that these busy spirits are not on that account divine, not worthy of worship or adoration.

In conclusion, then, “Christ, albeit a uniquely embodied spirit, should be considered part of animated nature rather than part of the divine nature, and so is not deserving of worship or adoration.”

The ancient Gnostics usually regarded Christ as a messenger from the true God, a perfect being who was not really human or material but simply clothed in the illusion of matter — not so different from Crowley’s doctrine that all beings are perfect, but clothed in veils of matter. Clayton takes us one step further toward Averse Gnosticism in his contrary vision of Christ, through a valorization of a world in which spirit is always subsumed under matter, rather than the other way around, up to and including Christ, the first-born of creation and the image of God. Yet Clayton still suggests, like the Gnostics, that we should not worship materiality — we must save our worship for the invisible God, and thus avoid giving our worship even to Christ himself.

4.

According to Michel Surya, Georges Bataille threw pages of the English Romantic poet William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell into the casket of his lover Colette Peignot on her death in 1938. Bataille’s affinity for this work of Blake’s is not surprising — Blake is perhaps the most prominent representative in history of a kind of Averse Gnostic, a devotee of the active and creative power of matter and metaphysical “evil.”

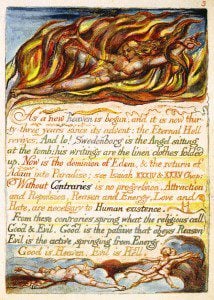

Blake’s revolutionary work established the influential notion that Heaven and good — traditionally associated with Reason and the soul — are static, while Hell and evil — traditionally associated with the material body — are dynamic and “energized,” Dionysian in energy. As Blake writes:

Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence.

From these contraries spring what the religious call Good & Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason

Evil is the active springing from Energy.

Good is Heaven. Evil is Hell.

Blake was an esoteric Christian influenced by — but not uncritical of — the almost Manichaean mystical theology of Emanuel Swedenborg. Unlike Swedenborg, Blake advocated devotion to the active, creative energies of Hell — to the sensual, the material, and the anarchic spirits represented in the Biblical mythos by fallen angels.

In fact, Blake suggests that the Nephilim, the half-angel, half-human creatures associated with transgression in the Old Testament account, were actually the “Giants who formed this world into its sensual existence … the causes of its life & the sources of all activity.” And Blake’s Messiah, Jesus Christ, is associated with these fallen creatures, and with Satan, who is a representative of a virulent creative energy closely resembling Bataillean base matter: “Messiah or Satan or Tempter was formerly thought to be one of the Antediluvians who are our Energies.”

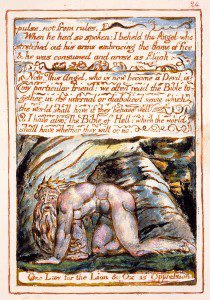

Towards the end of the Marriage, an angel of the high God attempts to argue with the Devil about the nature of Jesus Christ, pitting his orthodox Christian creed against the Satanic and base material creed of Lucifer. Lucifer wins, and the angel is convinced that Jesus Christ was in fact a representative of Hell, not Heaven, a hero of matter and sensuality and anti-authoritarianism. Blake concludes:

This Angel, who is now become a Devil. is my particular friend: we often read the Bible together in its infernal or diabolical sense which the world shall have if they behave well.

5.

In Blake, we have finally found a representative of the Averse Gnosticism, the worship of the demiurge, put forward by Georges Bataille. Blake is a Christian, but a Christian who, like Clayton, aligns Christ with the created angelic sphere clothed in matter rather than the invisible God above creation. Blake is a kind of Gnostic — indeed, he is considered a Gnostic saint of the Thelemic Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica — but an Averse Gnostic who, in the struggle between matter and spirit, sensuality and rationality, chooses the creativity of base matter over the stasis of idealism. Blake’s Christ has quite a bit in common with Blake’s Satan.

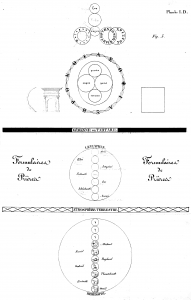

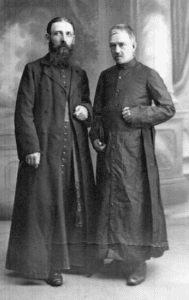

Bataille’s line of thought that an Averse Gnosticism is to be found among the practitioners of so-called black magic is a more difficult line to follow. But there is at least one strand of the French occult revival, whose milieu was surely well-known by Bataille, that — at least in the hands of its enemies, like the heresiologist accusers of Gnosticism in the ancient world — devoted itself to the triumph of matter over spirit. This is the Vintrasian heresy, a Roman Catholic heretical movement founded by the French mystic Eugène Vintras. Vintras received visions from the Archangel Michael, and strange phenomena accompanied his rites and rituals.

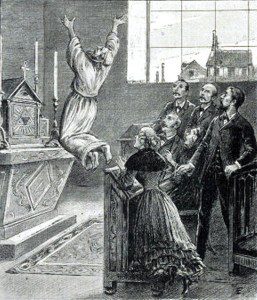

According to Éliphas Lévi, Vintras’ miracles were Eucharistic in nature —

Thousands of host appear on altars where there were none; wine rises in empty chalices, and it is no delusion, it is wine, a delicious wine; celestial music is heard; the fragrance of another world diffuses itself, and finally, blood — true human blood which doctors have examined — oozes and sometimes flows copiously from the Hosts, leaving mysterious characters thereon. (Mysteries of Magic, 318)

Eucaristic miracles of this sort are virulently material — base matter asserting itself as dynamic and sensual, the fecundity of Vintras’ spiritual power expressed as dangerously overflowing material abundance.

Lévi rejects the miracles of Vintras as Satanic in character, because the “mysterious characters” that appear on the bloody hosts — “hearts of all kinds, emblems of all sorts” — contain three signs which Lévi identifies as “the devil’s signature.” The first of these signs is the inverted pentagram, which Lévi associates with the “sign of the goat of black magic,” the “sign of antagonism and blind fatality, the goat of lewdness assaulting heaven with its horns, a sign execrated even in the Sabbath by initiates of a superior order” — a close parallel to the ancient acephalic talismans identified by Bataille as icons of demiurgic base matter. The second sign is a caduceus lacking the central line, with Hermetic serpents diverging rather than converging, with the V, the “typhonian fork, the character of hell,” above them. This sign signifies that “Antagonism is eternal; God is the strife of blind causes which perpetually create by destroying,” a fine summary of Bataillean base matter and its virulent properties.

Finally, Lévi identifies the monogram of YHVH, but reversed — “the most frightful of all blasphemies,” meaning “God and spirit do not exist … Matter is the grand totality, spirit the dream of demented matter. The form is more than the idea, the woman more than the man, pleasure more than thought, vice more than virtue, the multitude greater than its chiefs, children above their fathers, and madness more than reason” (324).

The material demiurge worshipped over the invisible God; base matter as the supreme power; spirit as always associated with a form of materiality; the triumph of the feminine, the sensual, metaphysical evil, political anarchism and creative madness. In other words, in his horror, Lévi has identified the symbols of Vintras, etched in blood on Eucharistic hosts — the material prison of the God-Man, figured in nineteenth century Catholicism as the ‘Prisoner of the Tabernacle,’ as emblems marking the Vintrasian cult as a Catholic left-handed tradition, a form of occult Averse Gnosticism.

Vintras emerges, in Lévi’s account, as Batalle’s black magic Gnostic. No wonder, then, that the heir of Vintras, the notorious Abbé Joseph-Antoine Boullan, espoused a form of sexual magic, of an occult spiritist cosmos not unlike Robert Clayton’s in which intercourse with lower beings raises them up in the cosmic hierarchy and intercourse with higher beings raises oneself. These Averse Gnostics saw the material-spiritual cosmos as a dynamic matrix in which base material spirits can rise or fall in the hierarchy, one dominated by the demiurge — Ialdabaoth in the old Gnostic tales, Satan in the poetry of William Blake, Jesus Christ himself in the sect of Eugène Vintras. Or, in the words of the heretic Clayton, “when certain jarring elements meet and break forth in ‘Thunder and Lightning, and Earthquakes, or any other mechanical Operations’ some spirits may become united to a different set of material organs, including organs of a more exquisite and delicate kind” (Duddy, 121).

The Averse Gnostic, of the kind envisioned in the philosophical reverses of Bataille, worships the demiurge; the dynamic, creative, virulent forces of an intransigent materiality. A symbol on Vintras’ perverse pontifical staff perhaps best emblematizes the decadent religious character of such a vision:

The hand with three fingers closed expresses the negation of the [supernal] triad and the assertion of purely material forces. A hand showing only the auricular is equivalent, in the sacred, symbolical language, to the exclusive affirmation of passion and savoir-faire. It is the scurrilous and materialistic version of the great words of St Augustine — “Love, and then do what you will.”

Not quite the Law of Thelema, but a close cousin — more sensual, more decadent, more Catholic in character: a true Averse Gnosticism in the spirit of Georges Bataille. Praise Ialdabaoth.

—

If you enjoyed this article, check out my new personal blog, The Light Invisible, for more pieces on Christian esotericism.

[Manager’s Note: all images in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.]

Patheos Pagan on Facebook.

the Agora on Facebook

The Blooming Staff is published on bimonthly on Tuesdays here on the Agora; follow it via RSS or e-mail!

Please use the links to the right to keep on top of activities here on the Agora as well as across the entire Patheos Pagan channel.