Bride, Brigit, Brigid, Brighid, Bríd etc. all mean high or exalted one. Because Her name is so widely known, there are many different ways to say it. Pronunciations and spellings vary due to different Gaelic languages and periods, don’t get hung up on it. Certain versions are more correct in certain contexts, that’s all. The name occurs in Sanskrit as Brihati, later we find it in Gaul as Brigindo, and still later in Britain as Briganti, and Ireland as Brigid.

There is a suggestion that the root name may apply to the goddess of people living in hills and mountains, which would fit the Brigantii a tribe who lived in the Alps in what is now western Austria around 1500 BC up until they were ousted by the Romans around 15 BC. It would also fit the Brigantes, who lived in the Pennines, in northern England, during the 1st c AD. They spoke a Brythonic language similar to Welsh, rather than a Gaelic language. A branch of the Brigantes settled in what is now County Wexford (in Ireland) in the province or Leinster.

There are a few inscriptions mentioning Brigando/Brigindu in the Brigantii heartland on the continent, and a handful of inscriptions to Briganti/Brigantia in northern England and southern Scotland. Place names with the root “brig” can be confusing where hills are concerned, because it’s not always clear whether it refers to the goddess, or just that the hill is a high place. However, the River Braint in Anglesey (Wales), the River Brent in England and several rivers bearing Brigid’s name in Ireland are more obviously connected to the goddess.

Since the early Celts didn’t write things down, the only other references we have are contemporary Roman writers who talk about a Celtic “Minerva”. The Romans tended to label foreign deities with the name of whatever Roman deity they thought was the closest equivalent. They related Her to arts and crafts, and probably to healing springs, such as the ones at Bath.

IN IRELAND

The next time we hear of Brigid is from the 9th century writings of Cormac, an Irish bishop who wrote a sort of encyclopaedic dictionary known as Cormac’s Glossary. Bishop or not, he clearly names Brigid as a goddess, saying that she was the daughter of the Dagda, that she was expert in filidhecht (poetry and oral learning), and that she had two sisters who were also called Brigid. One sister was associated with healing and the other with smith craft. He goes on to say that Brigid was a sort of general word for “goddess”.

In approximately the same period, the Book of Invasions lists her as a poetess, and as daughter of the Dagda. It discusses her associations with magical livestock and certain plains in Leinster associated with agriculture. Her magical livestock included the king of boars, king of bulls, and king of rams, – all of which used to cry out when rapine was committed in Ireland. The Torc Triath, the king of boars, is obviously cognate with the Twrch Trwyth, the magical boar mentioned in the Welsh tale of Culwch and Olwen.

In the second battle of Mag Tuired, Brigid is described as daughter of Dagda and wife of Bres, who is half Fomorian. They have a son, Ruadhán, fighting on the Fomorian side. The Fomorians notice that the spears of the Tuatha Dé Danann are superior to their own. Ruadhán is sent to investigate and asks the Tuatha smith, Goibniu, to make him a spear, which he does. He then flings the spear at Goibniu, who flings it back killing him. Brigid wails and cries, thus inventing the Irish custom of keening for the dead.

This is essentially all we know of the goddess Brigid from history, archaeology and myth.

ST. BRIGID

There are 15 different Irish saints called Brigid, perhaps reinforcing the idea that Brigid is a generalised deific or sacred name. The one who is considered to have inherited aspects of the goddess is Brigid of Kildare, who probably lived in the 5th century, although there are no contemporary mentions of her from that time. Like some other early saints, it’s possible that she never lived.

Modern Pagans generally believe that the Catholic Church co-opted the goddess Brigid and changed Her into St. Brigid, to popularise Christianity and downplay Pagan practices. This may well be the case, but there are some interesting political reasons why St. Brigid was pushed to the fore, as well. In the early 5th century the Uí Dhuínlainge (modern anglicised version Dowling/O’Dowling) dynasty came to power in Leinster. Their leader, who seized power in 633, was the brother of the Bishop of Kildare.

By 650 the first hagiography (a saint’s biography listing their miracles) of St. Brigid had been produced. Bishoprics could be seats of immense political power at the time, and ties to an important and popular saint could vastly increase that power. It was definitely in the interest of the Uí Dhuínlainges to promote Brigid as the holiest and most powerful of indigenous saints, bringing power, wealth and pilgrims to the region.

So it may have been less a question of replacing a goddess with a saint, and more a question of keeping Brigid and Leinster to the fore. I can’t help but be intrigued by the possible (but impossible to prove!) line from the Brigantii of Gaul, through the Brigantes of Britain and Ireland, to Brigid of Kildare. After all, Kildare is not far from where those 1st century Brigantes settled when they came to Ireland from Britain.

It may be that at some point in the past Kildare had been a Druidic centre. Cill Dare = chapel or the oak. Brigid may have been worshipped there or may possibly have been the title of some chief Druidess. Medieval historian Gerald of Wales wrote that St. Brigid and nineteen or her nuns guarded a sacred fire at Kildare, which burned perpetually and was surrounded by a hedge which excluded men. At least one Roman writer described “Minerva’s” temple in Britain as having a perpetual flame, as well.

The first hagiography of St. Brigid contains a fairly standard list of miracles associated with saints of the period, but also a few items which are typical of Celtic myth. Brigid is born at sunrise, neither within nor without a house – both references to liminality. She will only drink the milk of a white cow with red ears, a standard description of magical or otherworldly cattle. And the house in which she dwells appears to those outside to contain a blazing fire.

Later biographies say that she and her mother were sold into slavery to a Druid, for whom they did agricultural work. Thus, Brigid is essentially brought up by a Druid, suggesting that she inherits some special knowledge or power, but without any blood ties, which might have been a cause for concern.

One final story from a later biography that has always struck me is the story of the deathbed conversion of a stubborn Pagan. In this tale, St. Patrick has been trying to convert this man, but he has refused to change his beliefs. St. Brigid then makes her attempt and weaves a cross of rushes over the man’s bed, which somehow does the trick! I have to confess that this has completely put me off Brigid’s crosses for life.

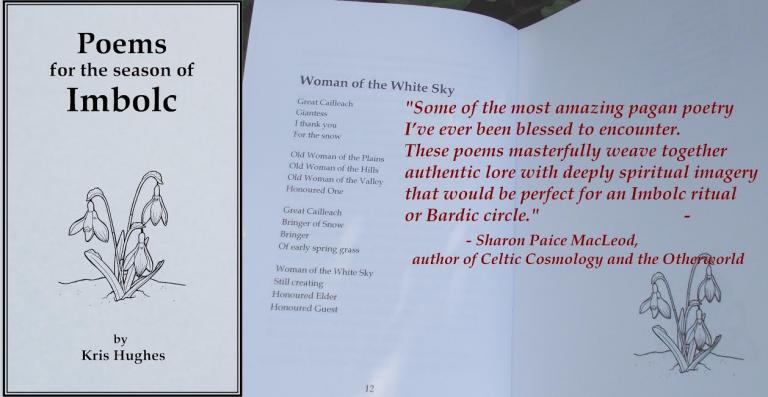

I had hoped to include something on Brigid and the Cailleach in Scottish folklore, but it would make this post too long, so I will save that for another time. However, if you can’t wait, I’ve written a few things on my own blog, such as We Need to Talk About The Cailleach and First There is a Mountain. I’ve also just published a little book of poetry on that very subject called Poems for the Season of Imbolc.

Further reading/my main sources:

Celtic Mythology – Prionsias Mac Cana p 32-34

The Lore of Ireland — Dáithí Ó hÓgáin p 50-55

On the web:

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsBritain/BritainBrigantes.htm

You can follow Kris at her blog Go Deeper and support her work on Patreon.