“Let us go,” said he, “to the mound, to sit there. And do thou,” said he to the page who tended his horse, “saddle my horse well, and hasten with him to the road, and bring also my spurs with thee.”

And they went and sat upon the mound; and ere they had been there but a short time, they beheld the lady coming by the same road, and in the same manner, and at the same pace.

“Young man,” said Pwyll, “I see the lady coming; give me my horse.”

And no sooner had he mounted his horse than she passed him. And he turned after her and followed her. And he let his horse go bounding playfully, and thought that at the second step or the third he should come up with her. But he came no nearer to her than at first. Then he urged his horse to his utmost speed, yet he found that it availed nothing to follow her.

Then said Pwyll, “O maiden, for the sake of him whom thou best lovest, stay for me.”

“I will stay gladly,” said she, “and it were better for thy horse hadst thou asked it long since.”

– (from Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation of the Mabinogion, which is in the public domain)

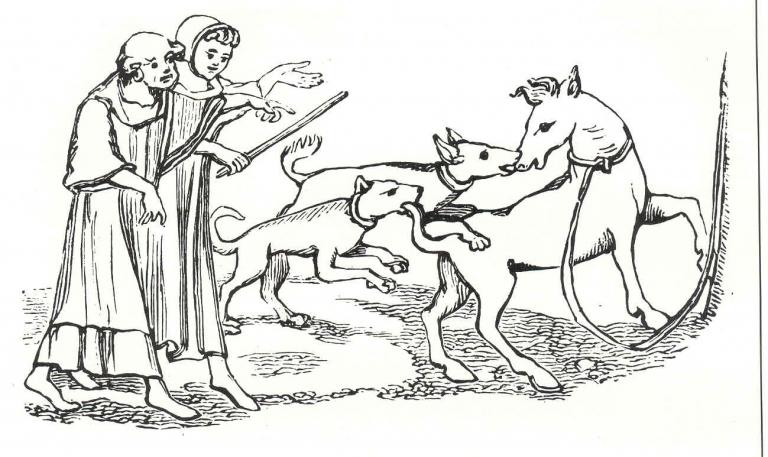

Some of you might recognise this as a passage from the First Branch of the Mabinogi, when Pywll and Rhiannon first meet. It’s a magical and romantic moment, in which Rhiannon takes time out from personal introductions and love talk to berate Pwyll for the way he treats his horse. We might think of this as no more than one of Rhiannon’s typical quips at Pwyll’s expense, but it is actually a remarkable statement. There is no indication that the welfare of animals, even the noble horse, was important to Britons in the 14th century, when the Mabinogi was written down. Although people undoubtedly did form attachments to some domestic animals, there is no evidence that they would have judged someone badly for spurring a horse. The picture of horse-baiting (below) comes from the same period.

Why this statement occurs is hard to tell. Is it merely meant to show Rhiannon’s sympathy or kinship with horses, or is there more behind it? Was it put into the story during the medieval period, or is it something which may have survived from an ancient aspect of the myth? I suspect it’s the latter. I see it as a clear directive from The Great Mare, in the person of Rhiannon, not to mistreat Her children. So do not expect me to be politely silent if I see you mistreating a horse.

Every week my social media feed shows horses being abused. I read about wild/feral horses being removed from their habitat, about pet horses suffering terrible neglect, horses abused in just about every sphere of competition and “equine sport”. Horses being shipped on long, terrible, bewildering journeys on their way to be slaughtered, and of people claiming to “rescue” horses, then holding them in the most squalid conditions. These things shock and upset most sane people, but not so many people see the slow drip, drip of hopelessness, of casual low-level abuse, of all the “loved” horses who are denied the right to carry out their natural behaviours. Horses who don’t get to walk around out of doors enough, who don’t get to socialise with other horses and eat a natural diet. Whose tack doesn’t fit properly, whose riders are too heavy and unbalanced, and who are trained with subtle forms of pain and intimidation that no one notices because it’s a cultural norm.

Don’t expect me not to care about that. Working for the horse goddesses isn’t just talking about mythology and lighting candles. Increasingly, I feel that it’s wrong to keep silent about this, at the same time knowing that it’s also counter-productive to alienate people who think they’re doing okay.

During the years that I spent with horses I sought tirelessly to understand and implement all that was good for them. When I say “good” I am not just talking about scientifically good nutrition, or a warm stable. I am not just talking about being kind to the horses I meet, or loving them. This goes much deeper than “natural” training methods or extra comfy saddles, although these were the things I started with many years ago. And I got a lot of things wrong.

To truly seek the good of horses, or a horse, is to let go of your agenda, of your ego, and very likely of your dreams. Horses can provide us with so many things. They are a means to do work, win prizes, find excitement, get exercise, look impressive, feel fulfilled, have an animal companion, or own something beautiful. We can make (and lose) phenomenal amounts of money racing them. We can breed them, and alter their characteristics to suit ourselves, and make money buying, selling, and training them. We can hold them up as representatives of our chosen culture, or the greatness of our ancestors. But which of these things is truly for their good, for their happiness?

As a child, then an adult, who loved horses, it didn’t take me long to be hooked on the whole package of stable-yards, lessons, and long rides in lovely places. It also didn’t take me long to start questioning the whole package. The way horses were trained, ridden, and kept didn’t seem fair. I moved from being simply a client/student, to being a working student, to a sometimes stable-girl and teaching assistant, and every step I took was more frustrating than the last. I was surrounded by people who loved horses, but who didn’t, or frequently weren’t able to, give them what they needed. Everything was a compromise, and those compromises rarely went in the horses’ favour.

I began to look for better ways to do things. In the mid-1990s, when I became a horse owner, the horse industry was in the middle of a kind of revolution. More “natural” and/or “scientific” training methods were gaining a lot of traction. There was interest in tack that was more comfortable for the horse, and methods of footcare that didn’t involve nailing on metal shoes. People were beginning to question the husbandry practices that had become traditional, and whether these reflected the natural ethology of horses.

All of this has moved things in the right direction, but not far enough. The compromises we ask horses to make are still too great. Which is not to say that I have all the answers. Not even close. But I will keep asking the questions, and I will keep putting those questions in front of anyone who will listen. If my questions cause some discomfort, then maybe that discomfort will encourage people to think beyond cultural norms.

Mustangs in a US Government Holding Pen – BLM Nevada – CC 2.0 Wikimedia

Happily, some enlightened people are coming to realise that domestic horses need the freedom to move and be outdoors, preferably 24 hours a day, every day. Some people are even questioning the ethics of riding horses at all, or even of approaching any animal with an agenda.

Meanwhile, many horse owners have either rejected the innovations that are available or haven’t even heard about them. Meanwhile, wild and feral equines the world over are living on borrowed time as their habitats are destroyed or appropriated for the use of humans. Meanwhile, the economic pinch that many people worldwide are experiencing means an increasing number of horses abandoned by one means or another, or neglected, or unwanted.

If you are wondering what you can do to help horses, then that depends on your situation. If you don’t have horses, my gut says do what you can to help the wild and feral ones, because if we lose them, they will be lost forever. This might mean giving to charities that are working to keep them where they belong, or it might mean working to keep the ecosystems they depend upon safe and healthy. And that is really working for the good of the entire natural world. Wild horses won’t be safe if their habitats are destroyed. They won’t be safe if we kill off the apex predators they require to control their numbers naturally, or if they don’t have clean water to drink. Helping wild horses stay wild helps everybody.

If you own or work with horses, please do everything in your power to make sure that they live as fulfilling a life as they can, in the recognition of the requirements of their species. That they have as much freedom of movement as possible, that they are members of a herd, that they are not frightened, intimidated or in pain due to the actions of any human, that they have an appropriate diet. When you have done all you can for the horses in your care, see what you can do for the rest.

You can follow Kris at her blog Go Deeper and support her work on Patreon.