Often they don’t precisely know,

those who sit first in a house,

whose kinsmen they are who come (later):

no man is so good

that no fault follows him,

nor so bad that he is of no use.

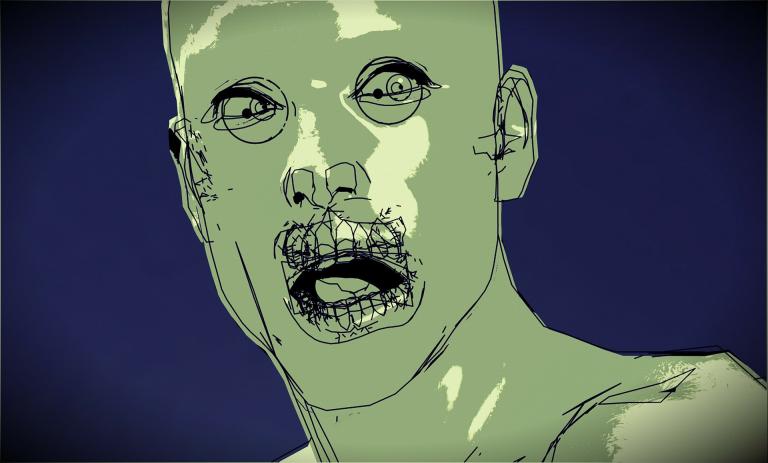

Let us speak of monsters: there are three.

(There will always be outliers, of course. These are monsters. It is not in their nature to be orderly.)

The first and least dangerous monster is the kind that you have made — the shunned child, the terrorized soldier, the desperate criminal. These are monsters of incidence, for without the inciting event and the grinding misery of life they would not be monsters at all. They are small monsters, and they are generally loud monsters, because their monstrousness comes from pain, and without expression pain is poison.

Do not suppose that this means they are limited in their capacity to inflict pain on others, or to destroy what is put before them, but understand that it is what makes them knowable. Somewhere, in these monsters, is a thorn which Androcles could remove. These are monsters which can, with effort on several parts (including that of the monster) be healed and become something less monstrous. The monsters you bred in them will always be part of them, now, but they need not always be the whole part, or the part with the most access to teeth.

(I hear you crying: but not everyone under such conditions as could make a monster becomes one. The fault is with the monster! The flaw is in them! So I will tell you: this is a comforting lie that we tell ourselves. It is a lie that we tell because it erodes our responsibility in the making of these monsters, and it makes them seem other than us. But they are not other. The fault is with us. The flaw is in us. When you subject something beautiful to stress to see if it might break, and it then shatters beyond repair, you are responsible for the destruction.

If your hands do violence, it is your violence.

This does not make monsters innocent. But neither are you.)

The second monster is the kind inborn. There is no event or action which creates this monster. It simply is, somewhere within a creature, and waits for its right time to bite and claw and cause chaos. It is the best shapeshifter of its like, and may linger beneath the skin forever, pacing between ribs, a hollow thing of hunger and violence. It is larger than the first monster, but it is also quieter, more inclined to subtlety, and to seek a position of authority and power before it slakes its appetite. It is, I believe, in all creatures somewhere — the only question is whether it is close to the skin, or buried in the place where shadows and forsaken dreams lie, or leashed to the purpose of its creature. It will always be a monster, because it was never anything else — it cannot unbe.

(This does not mean it should be destroyed– indeed, I do not believe it can be. There is a value to a thing which is always hungry, which does not know or understand fear, which is entirely teeth and danger. Given purpose and place, and constant attention and correction, it is a good guardian. Recall the many guardian monsters of the world — did you imagine they were always leashed? No: these were simply the monsters with good and clever masters, who saw value and worth in their existence. Recognizing that a monster cannot be allowed to rampage and cause unmitigated destruction does not mean that the monster must be slain. The monster is not the problem. The action is the problem. Behaviour can be modified, and failing that, channeled. This does not mean that no monsters should be slain. But it means you can probably send another monster to do it.)

The third monster is unknowable. It is basic, uncomplicated, innate chaos. It is Ginnungagap. It is the space between atomic particles. It is the space between stars. It is beyond comprehension, and thus beyond description. It is not my business, and my existence is very probably meaningless to it. It exists (and does not) and that is all (it is nothing).

(It is, like all monsters, an inextricable part of the weave. What? Did you forget the space between threads?)

The second thing to understand about monsters is that they will always exist. They always have existed, they exist today, and any fathomless paradise lacking monsters would stagnate and die on the vine, thus they must always exist in the ceaseless tomorrow.

The third thing to understand about monsters is that they, like all other things, can be loved.

I do not know if every kind of monster can feel or express love, although some of them certainly can. (We will speak of love another time.) But reciprocation is not, in fact, the point of love. If the monster loathes me, would bite and tear me, that has no bearing on whether or not I am able to love it, or even if I should love it. If there is love in me for a monster — strange, fearsome, untraceable love, which decides its own course; or the gentler affection that sometimes grows out of familiarity; or the deliberate choice of love, made with calculation and intent, sustained with effort and will — that is not the monster’s affair. Loving the monster does not even necessarily preclude destroying it, if it is sufficiently dangerous and sufficiently resistant to being healed or leashed as its nature warrants.

Like all emotions, and perhaps contrary to popular wisdom, love is a thing you feel, not a thing you do. What you do about love, how or even if you express it, is another matter entirely. You may even perform the actions of love without feeling it, if you are generous, or crafty, or a particular kind of monster, or all three.

Love does not tame monsters, or if it tames some, it does not tame all. It may, in fact, make monsters more dangerous, or focus them in a different way. Or they may ignore it entirely. Put aside this fairytale: love does not make monsters into men.

But it makes them beloved.

This is a thing I am not certain how to translate into words: a thing I know marrow-deep, sourcelessly, the way that I know that some kind of power sleeps in bones, and honey is sacred, and the right kind of wind carries someone’s attention. Here is the thing: whatever is beloved is, in its own small way, sacred. Place, or item, or creature, it makes no nevermind; if there is love in it, that is a sacred thing. Childhood toys, and secret groves, and lovers, children, soulmates, monsters: sacred all. Not in the way that gods are sacred — that is a very large and profound sacredness — but a small, familiar, candlelight sacredness. The kind you can carry with you.

Do you understand?

Being loved, beloved, sacred does not make the monster worthier or less dangerous, but it builds a home around it. You, who love the monster, live with it in the place your love has made — not a physical place, necessarily, but a place nonetheless. In living with it, you make that monster kin, with all the obligations and advantages that entails.

This is a dangerous thing to do. It is also, sometimes, a necessary thing to do.

It is particularly necessary if the monster is in you.

And now here is the secret: it is.

You have a monster in you. Hide it, leash it, slay it, love it — you have a monster in you.

No man is so good that there is no fault in him.

No man is so wicked that he is of no use.

Now understand: there are no monsters.

There are people. There is entropy. There is raw, simple chaos. There is you.