A really common question I see from people just starting out in Irish paganism is “where do I begin learning the mythology?” because there is so much out there it can be overwhelming. Usually there will be a variety of answers people give but I’d like to offer my suggestions here. I’m going to talk a bit about things to watch out for and then look at good places to start. I know the subject can be very confusing when people are just starting out so hopefully this will help a bit.

Understanding Irish Myths

So the first thing to know is that Irish mythology is divided into groups of related stories, usually referred to as ‘cycles’. There are four main ones: The mythological cycle, the Ulster cycle, the Fenian or Ossianic cycle, and the cycle of kings. There are, of course, other miscellaneous tales and different ways to group the stories but the cycles are common and cover a lot of material. By looking at the stories as they are grouped together in the cycles you have a clear arc to follow that links the individual episodes together and lends cohesion to everything.

It’s also important to understand that there isn’t any one definitive version of many of these stories and it’s very common to have multiple versions, or redactions, of various tales. The one exception is the Cath Maige Tuired, or Battle of the Plain of Pillars, which we only have one existing manuscript for. This means that it’s possible to have the same story show important differences between accounts, for example in one version it might be the Morrigan who does a thing while in another that same actions may be attributed to Badb. This can be a bit confusing at first but it shows the regional variations that the stories had when they were written down.

Discernment

Although I do think it’s important for people to read a diverse array of written material (or listen to audio material as the case may be) when we’re looking at mythology, particularly Irish, it is important to consider the quality of the material. Not all sources are created equal and sadly there’s a lot of bad material out there. Many of the easiest to access translations were done in a period when accuracy wasn’t necessarily a high priority and the translator freely added or edited out material.

For example in the public domain version of the Cath Maige Tuired the translator calls the Morrigan a lamia, which isn’t in the original text, and edits out a reference to her washing her genitals. This is not uncommon and it’s very important to understand that what you are reading in English may not reflect the original story but the translator’s opinion or mores. I suggest looking at things like when the material (in English) was printed, who wrote it and what their background is, and what audience they were writing for. All of these things can make a difference. You can also ask around among people who know about these things and get opinions about specific versions (for example I never recommend anything by Whitley Stokes if it can be avoided).

The Problem with ReTellings

Now to be clear there are very good retellings out there, so I am in no way trying to say they should be avoided altogether, and in fact the good ones are recommended. But it is necessary to go into retellings with an awareness that many of them are flawed and heavily altered. Lady Gregory’s Gods and Fighting Men takes some extreme liberties with the stories she tells, often changing details out of all recognition or adding things found nowhere else. Peter Berresford Ellis’s Celtic Myths and Legends adds a fictional Irish creation story which he wrote in with his other retellings without making it explicitly clear that it doesn’t exist in any older source.* So extra caution is needed with anything labelled as a ‘retelling’.

Where To Start

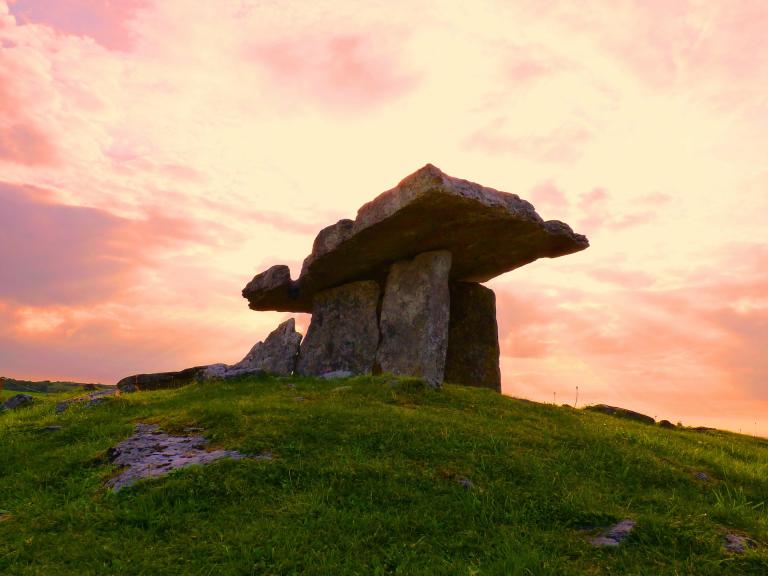

So, all of that covered. Where do you start? I recommend beginning with the mythological cycle which tells of the arrival of the Tuatha De Danann in Ireland and many of their stories. I think that beginning there will give a person a good grounding in the stories and in the Gods themselves. Key stories here would be the Cath Maige Tuired Cunga (first battle of the plain of pillars), the Cath Maige Tuired (battle of the plain of pillars), Tuatha De Danann Na Set Soim (Jewels of the Tuatha De Danann), How the Dagda got His Magic Staff, De Gabáil an t-Sida (the Taking of the Sidhe), Aislinge Oenguso (Angus’s Dream), and Oidheadh Chloinne Lir (Fate of the Children of Lir) and the Fate of the Children of Tuireann. This selection offers a firm grounding in the Tuatha De Danann, from their arrival in Ireland to some of the most significant events while they were there before the Gaels came. From there you can expand into other stories and other cycles.

Recommended Resources

Mary Jones Celtic Literature Collective – a fairly comprehensive website that groups the stories by cycle and includes English translations of many of the important texts.

Corpus of Electronic Texts (aka CELT) – harder to navigate but tons of great material.

MacAlister’s translations of the Lebor Gabala Erenn (book of the taking of Ireland) – one of the best versions available.

For more on the various Irish deities I do have a book called Pagan Portals Gods and Goddesses of Ireland that may be of interest. I also suggest looking to authors and folklorists in Ireland, as they are usually better sources than people who grew up outside the folklore and the myths.

*there is no Irish creation story in any existing text or manuscript