There have been many writers I have encountered over the years that have had a transformative influence on my life: Annie Dillard (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek), Alan Watts (Behold the Spirit), Emerson (“Self-Reliance”), and Theodore Roszak (The Making of a Counterculture). But there has only been one author who I identified so closely with that I have been tempted to believe in reincarnation.

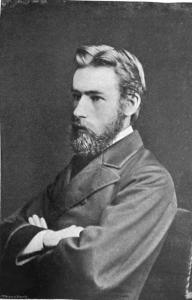

I’ve never believed in reincarnation really. I mean, I think it may happen for some people, but I haven’t had any reason to believe it has happened or will happen to me. However, reading the autobiography of John Trevor, the founder of the Labour Church in late 19th century England, I am so shocked by the resemblances, I have to wonder.

I’d like to periodically write about Trevor’s life here and compare it with my own. Trevor’s autobiography is called My Quest for God, and very much focuses on his journey to find God. It is very introspective, which I think was unusual for an autobiography of the time. I recently came across a review of his book in American Fabian which was both accurate and entertaining:

“It has 274 large, closely filled pages. It is an autobiography, and he goes with minute detail and often wearisome repetition into his ancestry, birth, breeding, development and life. He gives long extracts from letters that he has written to prove a statement he has made about himself which a reader at once believes because he makes it. He quotes at length from older sermons to show his state of mind at a certain time. And all this mass revolves around himself. He is an interesting character, but not interesting enough to justify 274 pages of self-dissection and self-analysis.

“Henry Ward Beecher once said that if you want to get dyspepsia, follow every mouthful of food down to feel, if possible, whether it digests or not and what becomes of it. It would seem as if Mr. Trevor must have mental indigestion, so continual is the introspection.”

As a person who is prone myself to excessive introspection, I appreciated the reviewer’s characterization.

Trevor’s book was published in 1897, but Trevor lived from 1855 to 1930, which is interesting in itself, since he published his autobiography at the young age of 42 and then went on to live another 33 years. Trevor’s book is hard to find in any library, but you can download it here.

What drew me to the obscure book was actually reading another, more well-known, book: William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience. In his chapter on mysticism, James quotes from Trevor’s autobiography as an example of a mystical experience. The experience stuck with me profoundly and years later I had to track down the source. Here was what Trevor wrote, near the end of his book:

“One brilliant Sunday morning, my wife and boys went to the Unitarian Chapel in Macclesfield. I felt it impossible to accompany them—as though to leave the sunshine on the hills, and go down there to the chapel, would be for the time an act of spiritual suicide. And I felt such need for new inspiration and expansion in my life. So, very reluctantly and sadly, I left my wife and boys to go down into the town, while I went further up into the hills with my stick and my dog. In the loveliness of the morning, and the beauty of the hills and valleys, I soon lost my sense of sadness and regret. For nearly an hour I walked along the road to the ‘Cat and Fiddle,’ and then returned. On the way back, suddenly, without warning, I felt that I was in Heaven—an inward state of peace and joy and assurance indescribably intense, accompanied with a sense of being bathed in a warm glow of light, as though the external condition had brought about the internal effect—a feeling of having passed beyond the body, though the scene around me stood out more clearly and as if nearer to me than before, by reason of the illumination in the midst of which I seemed to be placed. This deep emotion lasted, though with decreasing strength, until I reached home, and for some time after, only gradually passing away.”

Trevor then proceeds to explain the worth of such experiences as he understands it:

“The spiritual life justifies itself to those who live it; but what can we say to those who do not understand? This, at least, we can say, that it is a life whose experiences are proved real to their possessor, because they remain with him when brought closest into contact with the objective realities of life. Dreams cannot stand this test. We wake from them to find that they are but dreams. Wanderings of an overwrought brain do not stand this test. These highest experiences that I have had of God’s presence have been rare and brief—flashes of consciousness which have compelled me to exclaim with surprise—God is here!—or conditions of exaltation and insight, less intense, and only gradually passing away. I have severely questioned the worth of these moments. To no soul have I named them, lest I should be building my life and work on mere phantasies of the brain. But I find that, after every questioning and test, they stand out to-day as the most real experiences of my life, and experiences which have explained and justified and unified all past experiences and all past growth. Indeed, their reality and their far-reaching significance are ever becoming more clear and evident. When they came, I was living the fullest, strongest, sanest, deepest life. I was not seeking them. What I was seeking, with resolute determination, was to live more intensely my own life, as against what I knew would be the adverse judgment of the world. It was in the most real seasons that the Real Presence came, and I was aware that I was immersed in the infinite ocean of God.”

What struck me about Trevor’s experience was that he did not disassociate it from his real life in this world. He says he had these mystical experiences when he was living life to the fullest, and the experiences themselves made his life seem more real, not less. These were the kind of experiences I have had and want to continue to have.

So that’s it for Trevor for now. Next time I come back to him, I will write a little about his childhood: his intensity, his sensitivity, and the beginning of a long struggle with something he never names, but I think quite obviously was masturbation. Later I will write about how he lost his faith in the Christian religion and actually started sounding quite Pagan! (I honestly got chills when I read this part.)