I’ve often wondered what it is that makes humans human. Is it our developed forebrains and opposable thumbs? We’ve named ourselves homo sapiens. We are the wise apes. We make tools. We make war.

Eliade called us homo religiosus. We are the animals that bury our dead. Others have proposed that what makes us human is our self-consciousness. I believe that what makes us unique, alone among all the other animals on the planet, is our experience of being alone — our experience of loneliness, of alienation, of disconnectedness. Of course, other animals do appear to experience loneliness, especially pets. But I am referring to that uniquely human experience of disconnectedness or alienation which we can feel even when we are surrounded by other people.

The experience of alienation is tied up in my mind with notions of sacrality — what is sacred and what is mundane. Pagans frequently say that everything is sacred, but we still struggle with our experience of the mundane, as Teo Bishop’s recent blog post indicates. For me, the experience of connectedness defines the sacred — the connection of mind to body, of body to other bodies, of our bodies to the earth, of the earth to the cosmos. When I think back to the times in my life when I felt most connected — to other people, to the world around me, to my own body — those were my most sacred moments. As far as we know, we alone of all the beings on this planet can experience disconnectedness. And for me, that sense of disconnection or alienation defines the mundane.

The fact of alienation is, or course, at the heart of the Christian experience. The story of Adam and Eve’s fall is an archetypal story of the separation from the sacred which we all experience at some time in our lives. I think Christianity has this much right. Where I think Christian thought goes wrong is when it asserts that the condition of alienation is the “natural” state of humankind and when it perpetuates the experience of alienation by advocating an anti-body ethos. The body, I believe, is the door that leads out of the solipsistic mind. It’s a shame (pun intended) that Christianity adopted this anti-body ethos, because the Christian doctrine of incarnation has real potential to bridge experience of the separation between mind/spirit and body.

Alienation does not feel like my natural state. The sacred experience of connection — that is what feels “natural”. So how do we lose that? It is a strange experience — the mundane. Where does the sacred go when it goes? It seems clear to me at least that the sacred doesn’t go anywhere. It’s not the world that changes, but me, when I feel the loss of the sacred. While the world is and remains essentially sacred, we humans can nevertheless experience it as mundane. (I find the existentialists’ distinction between “essence” and “existence” useful here.) Pagans affirm that the world is not fallen, that we are not fallen. In our essence we are not disconnected, but we can still experience disconnection existentially.

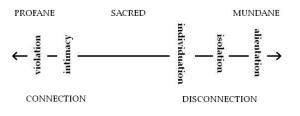

I’ve been talking about the sacred and the mundane, but where does the “profane” fall into this discussion? I imagine a spectrum of connectedness and disconnectedness. As we move toward greater disconnection, we move through individuation to isolation and alienation. I equate this with the experience of the mundane. As we move in the other direction toward greater connection, we move through intimacy to violation.

Violation can be understood as an excess of connection, getting too close, crossing boundaries. I equate this with the experience of the profane. Examples include rape, a profanation of the intimacy of sex, or entering a temple without permission, a profanation of the intimacy with the presence of divinity that is believed to reside there. The sacred, then, is to be found in the space between the mundane and the profane, between the excesses of alienation and violation … where intimacy and individuation are in balance.

In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard discusses mystical experiences in a way that elucidates this dynamic. In one such experience, Dillard is sitting at an interstate gas station, patting a puppy, and appreciating the beauty of the natural world around her and then …

“This is it, I think, this is it, right now, the present, this empty gas station, here, this western wind, this tang of coffee on the tongue, and I am patting the puppy, I am watching the mountain. And the second I verbalize this awareness in my brain, I cease to see the mountain or feel the puppy. I am opaque, so much black asphalt.”

She goes on to explain how, when she lost the experience, it was herself that changed, not the world around her:

“But at the same second, the second I know I’ve lost it, I also realize that the puppy is still squirming on his back under my hand. Nothing has changed for him. He draws his legs down to stretch the skin taut so he feels every fingertip’s stroke along his furred and arching side, his flank, his flung-back throat. I sip my coffee. I look at the mountain, which is still doing its tricks, as you look at a still-beautiful face belonging to a person who was once your lover in another country years ago: with fond nostalgia, and recognition, but no real feeling save a secret astonishment that you are now strangers. Thanks. For the memories. It is ironic that the one thing that all religions recognize as separating us from our creator—our very self-consciousness—is also the one thing that divides us from our fellow creatures. It was a bitter birthday present from evolution, cutting us off at both ends.”

Dillard describes her sense of loss as a separation and a division, so I hope I am not putting words in her mouth when I characterize her experience as one of connectedness. And I would describe her experience as an example of an experience of the sacred and her loss of that experience as a lapse into the mundane.

Dillard goes on to describe how consciousness both makes this experience possible and also interferes with it:

“I thought, with rising exultation, this is it, this is it; praise the lord; praise the land. Experiencing the present purely is being emptied and hollow; you catch grace as a man fills his cup under a waterfall. Consciousness itself does not hinder living in the present. In fact, it is only to a heightened awareness that the great door to the present opens at all. Even a certain amount of interior verbalization is helpful to enforce the memory of whatever it is that is taking place. The gas station beagle puppy, after all, may have experienced those same moments more purely than I did, but he brought fewer instruments to bear on the same material, he had no data for comparison, and he profited only in the grossest of ways, by having an assortment of itches scratched. Self-consciousness, however, does hinder the experience of the present. It is the one instrument that unplugs all the rest.”

In other words, to have the kind sacred experience that she describes, one must have balanced heightened consciousness with a certain unself-consciousness. I’m not sure I agree that any self-consciousness at all interferes with the experience of the sacred. But extreme self-consciousness does lead to a sense of isolation and alienation that is characteristic of the mundane in my opinion.

On the other hand, the experience of the sacred is also not a total loss of self into a Universal Brahman. It is not a return to a pre-conscious state of infantile existence. It is rather an experience of profound connection between self and world — a connection which presumes a separation to begin with. Ken Wilbur describes this as a trans-personal consciousness, as opposed to pre-personal consciousness.

All of this brings me around to the original question, which is: If Pagans believe everything is sacred, why do we act like it isn’t? Or to put it in more practical terms, if the Goddess is always already present, why do we invoke her? This is just a tentative response, but I think the answer lies in the identification of the sacred with the experience of connection. Connection implies the existence of its opposite, disconnection. So in order to experience the sacred, we must experience both connection and disconnection — at to some extent we must experience them both simultaneously.