The latest brouhaha in the Pagan blogosphere is Sam Webster’s post “Why You Can’t Worship Jesus Christ and Be Pagan”. Jason Mankey has written a great response to Webster’s post and I highly recommend it. I’m not going to repeat all the points that Jason makes, most of which I completely agree with. Let me sum up by saying that, in order to claim that Christianity and Paganism are antithetical, one must define both Christianity and Paganism, and in doing so you will inevitably inevitably define one or both too narrowly for some people. (Another great response to Webster was posted by Pagan Layman, “Is Christianity the Enemy?”. Check it out too!)

I have my own definitions of Paganism and Neo-Paganism and my own definition of Christianity, and for me Neo-Paganism and Christianity are mutually exclusive. But at the same time, I don’t exclude the possibility or the legitimacy of Christo-Pagans, Christian Witches, Judeo-Pagans, Jewitches, etc.

You can worship Jesus and be Pagan, just not the way that I am Pagan. Webster would have been better off titling his post “Why You Can’t Worship Jesus Christ and Be My Kind of Pagan“.

And the fact that Webster doesn’t qualify his statements in this way justifies, I think, Jason’s characterization of him as a “Pagan fundamentalist.” It’s worth noting that at least some of the issues Webster has with Christianity, like imperialism and intolerance, are really products of fundamentalism, the same kind of fundamentalism that he is himself guilty of. (Not that I have not been guilty of Pagan fundamentalism sometimes myself.)

Neo-Paganism as a Christian Reformation

While I define my kind of Paganism, specifically Neo-Paganism, in contrast to the transcendental theism and asceticism of (some forms of) Christianity, it is nevertheless deeply indebted to Christianity for other reasons. Others have often defined Neo-Paganism in contrast to Christianity too (consider Isaac Bonewits’ definition), but the relationship is more complex than such definitions suggest.

In 1986, Margot Adler interviewed Kelly, the founder of the NROOGD, for her updated volume of Drawing Down the Moon. Adler shocked some readers by reporting that Kelly had returned to Catholicism:

“Aidan has now turned the tables upside down. He now believes that all visions of a universal Goddess come from the influence of Christianity—not the reverse. The Goddess movement is not Pagan he says, but a radically dissenting type of Christian sect. It is not Mary who is a pale reflection of the Great Goddess, he argues, it is the idea of a Great Goddess that is dependent on ideas about the Virgin Mary. The Goddess, he says, is merely a ‘de-Christianized and backdated’ version of Mary. Even the vision of Isis in The Golden Ass by Apuleius is, he believes, a creation influenced by Christianity.”

Kelly’s return to Christianity, not to mention his view of Neo-Paganism as derivative of Christianity, was seen as a betrayal by many Wiccans and Neo-Pagans, who viewed their religion as post-Christian.

In 1991, Kelly published his Crafting the Art of Magic, where he observed Wicca satisfies a modern need for a sacramental experience of sex, and suggests that, if the Catholic Church did this, there would be no need for Wicca. Personally, I think, if the Catholic Church offered a sacramental experience of sex, it really wouldn’t be the Catholic Church any more. The absence of a sacramental experience of sex is part and parcel of the conceptual separation of spirit and matter in Catholic Christianity, which is precisely where Christianity and Neo-Paganism diverge. So, Kelly’s statement is really like saying, “If authoritarian regimes would give people the vote, they would not need democracy.” Still, I find Kelly’s assertion that Neo-Paganism is a “radically dissenting Christian sect” interesting.

[Note: In 2006, Lisa Harris reported that Kelly had returned to Neo-Paganism. Kelly attributed his return to Catholicism to the need for counseling for an alcohol addiction. (“Look Back in Controversy: A Samhain Interview with Aidan Kelly”, Widdenshins, vol. 8, no. 5 (2006)). Kelly now blogs for Pagan channel at Patheos.]

Kelly is not the only person to have recognized a connection between Christianity and some forms of Paganism. Isaac Bonewits distinguished Neo-Paganism from what he called “Meso-Paganism” (which included Wicca) precisely in terms of their respective relationships to Christianity. He recognized that Meso-Paganism (including Wicca), at least, was “heavily influenced (accidentally, deliberately and/or involuntarily) by concepts and practices from the monotheistic, dualistic, or nontheistic worldviews of … Christianity”.

The connection of Wicca to Christianity has been explored by others as well. In 1996, British religious studies scholar, Linda Woodhead presented a paper at the Nature Religions Today Conference in England. Jone Salomonsen reported on the unpublished paper in her book, Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco (2002). According to the Salomonsen, Woodhead had suggested:

“that the ‘new spirituality’ that today flourishes in contemporary western societies represents a single form of religiosity, and that pagan Witchcraft is merely one of its expressions. This ‘new spirituality’ is deeply rooted in European Protestantism and has arisen as a response to an increasing dissatisfaction with Christianity (and Judaism) […] Although the self-understanding of Witchcraft is to reject this whole tradition, not to revitalize it, nor purify it from within, Woodhead argues that the most important context in which to understand pagan Witchcraft is a Christian Context: Witchcraft is not a new religion, but a reformation.“

Salomonsen, for her part, appeared to agree that Witchcraft is not post-Christian, but only post-church or post-synagogue, a “subcultural branch of Jewish and Christian traditions.”

In 2007, Joanne Pearson took up this claim in her Wicca and the Christian Heritage: Ritual, Sex and Magic. Pearson argued that Christianity is the “real invisible player” in the history of Wicca and then sought to attempt uncover this Christian heritage of Wicca, giving special attention to the heterodox Christian movements of nineteenth century Britain and France. Although she stops short of Woodhead’s claim that Wicca is a “new reformation” or a “bastardized version of Christianity”, she nevertheless concludes that “if heresy and witchcraft are constructs of the Christian imagination [as Wiccans claim], then a Christianity that has been constructed as ‘other’ by some Wiccans is also a product of imagination.” Sam Webster would do well to take note of this statement and observe how his own construction of Christianity as “other” is a product of his imagination. While he recognizes (correctly, I think) that paganism is the (Jungian) Shadow of Western civilization, Webster fails to recognize (and integrate) the Shadow of his own brand of Paganism: Christianity.

Christo-Pagan Mythology and Theology

One area that particularly interests me in the overlap of Christian and Pagan is in the area of mythology. This is especially apparent in the case of the Neo-Pagan Triple Goddess and Horned God. The Neo-Pagan Triple Goddess can be traced back, not to ancient pagan goddess triplicities, but to the author Robert Graves, and from him to Jane Harrison. Harrison related the Mother and Virgin figures of Demeter and Kore to the Christian Father and the Son in term of their relationship to each other, being two-in-one. She states in her Prologomena to the Study of Greek Religion:

“It has been shown in detail that the Mother and the Maid are two persons, but one god, are but the young and old form of a divinity always waxing and waning. It is the same with the Father and the Son; his is one but he reflects two stages of the same human life.”

Harrison in turn was deeply influenced by Sir Arthur Evans and his discoveries from Crete. (Harrison wrote autobiographically of her encounter with Evans in her “Reminiscences of a Student Life”.) Ronald Hutton has observed that Evans’ interpretation of the Cretan deities as manifestations of a single Great Goddess and her subordinate son and consort was based on the classical legend of Rhea and Zeus, “but his insistence that she had been viewed as both Virgin and Mother, with a divine child, owed an unmistakable debt to the Christian tradition of the Virgin Mary.”

Similarly, the Neo-Pagan God can be connected historically to to both Jesus, on the one hand, and his demonic other, on the other hand. Ronald Hutton describes how the Neo-Pagan God developed out of the “Green Jesus” figure of Romantic poetry, the benevolent face of the pagan Pan. (See Patricia Merivale’s Pan the Goat God: His Myth in Modern Times (1969)). He is also related to James Frazer’s dying and reviving vegetation spirit, which Frazer intended as a critique of Christianity. (See Robert Nolan Puckett’s thesis, “Plucking the Golden Bough: James Frazer’s Metamyth in Modern Neopaganism” (1999). Note: I can send interested parties a copy which Puckett sent to me.)

Hutton also points out that the Neo-Pagan God has a more obvious, and less sympathetic parallel in Christian myth. In his Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles, he refers to the Neo-Pagan Horned God as the “paganization of the Christian Devil”, rather than the other way around. There is a good argument to be made that Neo-Pagan Horned God is a Romantic and Modern re-paganization of medieval Christian Devil imagery, making the Horned God once removed from the Christian Devil, but twice removed from any ancient pagan horned god. I would go even further and say that, to the extent that the Christian Devil with his various animal characteristics represents the animal and sexual natures of humankind, the Neo-Pagan Horned God represents the apotheosis of the Christian Devil.

In his essay, “The Legend of the Descent of the Goddess” (2003), Ceisiwr Serith (author of A Book of Pagan Prayer) gives another example of the Christian origin of Pagan myth, suggesting that the “Legend of the Descent of the Goddess”, the central myth of Wicca, may be a paganized version of the harrowing of hell and Jesus’ passion (i.e., his submission to death). Gerald Gardner himself compared function of the Legend in Wicca to the function of the myth of the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ in Christianity.

Another favorite myth of Pagans is the myth of the pagan origins of Christianity. What’s interesting is that the origin of this myth may lie in the Protestant Reformation. While the myth of the pagan origins of Christianity has some basis in fact (Christianity did arise in a pagan culture after all), Sabina Magliocco describes in her book, Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America, that the myth originates with the Protestant reformers for whom

“the core of Christianity was the individual’s personal relationship with God, and they interpreted folk religiosity as pagan contamination. They sought to purge Christianity of these impure accretions, and focused specifically on manifestations they considered extraneous to that relationship: particularly, the cults of the Virgin Mary and the saints, and secular amusements associated with liturgical feasts. Their impropriety was attributed to their preservation of elements the Protestant reformers considered hallmarks of Classical paganism: idolatry, in the form of saint’s cults, and goddess debauchery, the case of popular entertainments. When Oliver Cromwell and his followers railed against ‘the old religion’ and forbade the performance of popular year-cycle customs, they were targeting the practice of Catholicism and customs associated with it, not the actual observance of pagan religions. A connection however ill-conceived was formed in European, especially British, thought between the practice of folk rituals and customs and ‘paganism’.”

In addition to the overlap in mythology, there is theological overlap between Christianity and Neo-Paganism. In “New Age and Paganism” (published in Graham Harvey’s Paganism Today), Michael York distinguishes ancient paganisms and Neo-Paganism theologically. Ancient paganisms, according to York, perceived of divinity as radically plural, whereas Neo-Paganism is duo-theistic or a qualified polytheism that is really monistic with polytheistic manifestations. York locates the origin of Neo-Pagan theology in Christianity:

“Contemporary expressions of Neo-paganism are to me more of an updating and rectification perhaps of an essentially Christian attitude which is different from the free-ranging and loosely defined multiplicity of personalities and forces and deities which collectively constitute the [ancient] pagan godhead.”

A good example of this is the monistic “Dryghtyn” of Wiccan theology, which likely has its origin in Christian monotheism. (See the comments to Star Foster’s post about Valiente here, as well as the comments to Chas Clifton’s post on Gardner’s theology here.)

Roots and Branches

A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse;

from his roots a branch will bear fruit.

— Isaiah 11

Whether or not Neo-Paganism is accurately characterized as a Christian “reformation”, it cannot be disputed that Neo-Paganism arose in the context of a Christian culture, just as Christianity arose in the context of a pagan culture. So it should be no surprise that some Neo-Pagans today have integrated Neo-Paganism and Christianity. Ronald Hutton has observed that many proto-Neopagans saw no inherent contradiction between paganism and Christianity. These include Dion Fortune, W.B. Yeats, and Ernest Westlake. Regarding Westlake, the founder of the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry, Hutton writes:

“To Ernest himself, the attraction of paganism was not that it would replace Christianity but that it would cope with precisely those areas in which the latter had become deficient, and so (at best) to help revivify it. He coined the aphorism ‘one must be a good pagan before one can be a good Christian.’“

And let us not forget Gerald Gardner himself, who wrote in The Meaning of Witchcraft:

“It is usually said that to be made a witch one must abjure Christianity; this is not true; but they would naturally not receive into their ranks anyone who was a very narrow Christian. They do not think that the real Jesus was literally the Son of God, but are quite prepared to accept that he was one of the Enlightened Ones, or Holy Men. That is the reason why witches do not think they were hypocrites ‘in time of persecution’ for going to church and honouring Christ, especially as so many of the old Sun-hero myths have been incorporated into Christianity; while others might bow to the Madonna, who is closely akin to their goddess of heaven.”

Does that make Neo-Paganism a “radically dissenting type of Christian sect”, a “Christian reformation”, or a Christian heresy, a “bastardized version of Christianity”? Or is it something else entirely? At least in its early years, Christianity may very well have been described as a Jewish sect. It eventually came to be recognized as something distinct, however. It’s hard to imagine someone today confusing Neo-Paganism with any form of Christianity, but it’s not uncommon for Pagans to accuse one another of being closet Christians.

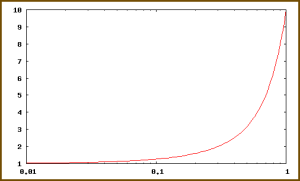

In any case, it’s clear that Neo-Paganism is not the antithesis of Christianity, any more than Christianity is the antithesis of Judaism. I think Neo-Paganism may be better described as branching off from Christianity, perhaps peeling away at a gradual curve, rather than intersecting it at the right angles that Sam Webster describes. We might even imagine that Paganism is like exponential curve in relation to the horizontal x-axis of Christianity.

If Christianity is the horizontal line at the bottom, then Christo-Paganism might be located on the red line near the middle at 0.1, Sam Wester’s Paganism would be located at the top of the red line at 1.0, and my own Neo-Paganism might be located somewhere between those two.

I like the idea of a Neo-Paganism rooted in Christianity, not just reacting against it, but drawing from it. In 1915, Carl Jung wrote a letter to Freud in which he described a vision of psychoanalysis transforming Christianity into a new paganism:

“I think we must give it [psychoanalysis] time to infiltrate into people from many centers to revivify among intellectuals a feeling for symbol and myth, ever so gently to transform Christ back into the soothsaying god of the vine, which he was, and in this way absorb those ecstatic instinctual forces of Christianity for the one purpose of making the cult and the sacred myth what they once were — a drunken feast of joy where man regained the ethos and holiness of an animal. That was the beauty and purpose of classical religion, which from God knows what temporary biological need has turned into a Misery Institute. Yet what infinite rapture and wantonness lie dormant in our religion, waiting to be led back into their true destination. A genuine and proper ethical development cannot abandon Christianity but must grow up within it, must bring to fruition its hymn of love, the agony and the ecstasy over the dying and resurgent god, the mystic power of the wine, the awesome anthropophagy of the Last Supper — only this ethical development can serve the viral forces of religion.”

Setting aside the question of whether early Christianity ever conformed to Jung’s Dionysian vision of it (it probably didn’t), the transformation of Christianity that Jung describes corresponds neatly with the development of Neo-Paganism as described by Ronald Hutton, a development that was influenced by the “Green Jesus” of the Romantic poets (i.e., Pan), the dying god of James Frazer and Robert Graves (see Graves’ King Jesus), and the descensus averni (descent into hell) of the “Hero With a Thousand Faces” described by Joseph Campbell (compare the Harrowing of Hell motif in Christianity). Whether these artists and scholars were bringing out the essence of Christianity or transforming it into something new, all of their works were firmly rooted in the rich loam that was Christianity, the same soil that gave birth to the Neo-Paganism that I practice today.