“There is another world, and it is this one.”

— Paul Eluard

I recently got turned on to Lev Gossman’s novel, The Magicians, after reading a review by Matthew Bowman on the Peculiar People blog on the Mormon channel at Patheos. So I bought the book, and I just finished it. It was excellent. As Bowman explains, The Magicians, is like Harry Potter, “if Harry Potter coped with his angst through cynicism, sarcasm, and eye-rolling, like real humans.”

Bowman’s review caught my attention for two reasons. First, he compares The Magicians to Richard Yates’ Revolutionary Road, which I absolutely loved. But it is a curious comparison, since Revolutionary Road has got to be the most disenchanted book ever written. It is starkly, painfully realistic. (I went into a months long depression after reading it.) Both Revolutionary Road and The Magicians reveal that the emptiness of middle-class suburban life is not the result of geography, but really an internal emptiness that we carry with us wherever we are. Revolutionary Road does this by giving its characters a chance to escape (to France), a chance while they proceed to sabotage out of fear and lack of imagination.In contrast, The Magicians does this by actually allowing its characters to escape, first to a magical prep school (Brakebills) and then to another Narnia-like dimension (Fillory). In both instances, the characters fail to realize that they cannot escape the emptiness within themselves.

When the main character in The Magicians, bright but socially awkward Quentin, is carried away to Brakebills, at first he is in heaven. Magic is real and he is going to be a magician. Magic is hard, both mentally and physically, but Quentin loves it all the more. What can be more exciting to a nerdy teenager? But eventually, Quentin finds himself unsatisfied and unhappy. The more he is able to bend physical reality to his will, the more desperate he becomes. “Wasn’t there a spell for making yourself happy?” he wonders.

Magic, for Quentin, has become disenchanted. It becomes mere technology. It becomes mundane. He longs for purpose, for meaning.

“In Brooklyn reality had been empty and meaningless—whatever inferior stuff it was made of, meaning had refused to adhere to it. Brakebills was different. It mattered. Meaning—is that what magic was?—was everywhere here.”

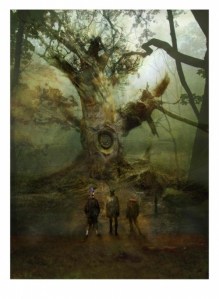

And he doggedly looks for these things outside of himself. He longs for adventure, for a quest, for a great evil to fight, i.e., all forms of meaning exterior to himself. Specifically, he longs for Fillory, the fictional world of the fantasy novels of his childhood which resemble C.S. Lewis’ Narnia. In short, he longs for magic, which is of course ironic. The magic of Fillory which he longs for is not technological, but “religious”. At one point, after Quentin expresses his desire to live in Fillory, Quentin’s girlfriend, Alice (also a student magician) remarks:

“That’s what makes you different from the rest of us Quentin. You actually still believe in magic. You do realize, right, that nobody else does? I mean, we all know that magic is real. But you really believe in it. Don’t you.”

The other thing that caught my attention about Bowman’s review was this quote:

“And magic, as a marvelous speech partway through the novel informs us, is the last resort of those people who hurt so much that they are never satisfied with the fact that our desires alone cannot force reality into what we want it to be.”

The speech in question is delivered by Brakebill’s headmaster on the eve of Quentin’s graduation. He declares that what makes the students magicians is not that they are more intelligent or more brave or more good than anyone else. It is because they are unhappy, they are wounded, they are in pain. And magic provides them the power to “break the world that has tried to break them.” It’s an optimistic perspective. And it’s also untrue, as the rest of the story demonstrates. Being magicians, the characters never really have to grow up. (They never move beyond the “magical thinking” phase of development.) “Can a man who can cast a spell ever really grow up?” muses the headmaster. And, upon graduation, the characters proceed to squander their gifts, and their lives. Because they are magicians, they never have to face hard, unyielding reality … until they do.

And ironically they discover it in the fantasy world of Fillory, which turns out to be a real place, with real danger, and (as Fillory’s Aslan-like character instructs them) not just a themepark created for their entertainment. And when enough people have been hurt and enough people have died, Quentin has to face the fact that he cannot escape himself or the gaping wound in his soul. No magic, no other world, will fix it. Right before the climactic denouement, Alice challenges Quentin:

“Stop looking for the next secret door that is going to lead you to your real life. Stop waiting. This is it: there’s nothing else. It’s here, and you’d better decide to enjoy it or you’re going to be miserable wherever you go, for the rest of your life, forever.”

And, at the end of the book, it seems that Quentin never really learns this lesson.

I recognized myself in Quentin (just as I did, embarrassingly, in Yates’ Frank Wheeler). I’ve written here before about my teenage fantasy of being whisked away to a fantasy world of swords and sorcery. Specifically, I longed to be Margaret Weis’ character, Raistlin, from the Dragonlance novels.

While I was neither as physically challenged, nor as mentally disciplined as Raistlin, I liked to imagine that I was, exaggerating both my sense of persecution and my self-image as “special”. Reading Grossman’s The Magicians got me wondering about what its is drove (drives) me to this fantasy.

I like science fiction too, but there is no doubt that fantasy is my preferred … well, fantasy. For one thing, I’m pretty sure that the future will look more like William Gibson’s Neuromancer or Blade Runner than Star Trek. But the real reason I prefer fantasy is magic. What makes fantasy different from science fiction is not whether they are set in the past or future — the difference is magic. Sure, advanced technology is great. It offers the same sense of power, control over one’s world, that magic does. But it’s still not magic. Arthur C. Clark, the author of the science fiction novel, 2001: A Space Odyssey, wrote: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” And while that true in a sense, it’s also not true in another sense. We live in a magical world now, in the sense that many of the technologies we take for granted would appear to be magic to someone living only 200 years ago. But we don’t experience them as magic. And that’s because technology is not magic. This becomes clear in Grossman’s novel, when magic becomes disenchanted for Quentin, as it becomes a mere technology for manipulating his environment.

What’s the difference between magic and technology then? I think that the difference is this: Magic is meaningful. Technology is not. Magic is the experience of “something more” — that same something that Quentin kept searching for, looking for around every corner. Magic, like meaning, is something that has be be believed in. Belief is irrelevant to technology. And, most importantly, magic has to come from within, while technology is external to us.

This is what Quentin never realizes: The magic that he is looking for, the world of meaning and purpose, has to be found within himself, or not at all. It seems trite, but it is so hard to learn, as I know from experience. (I continually have to relearn it.) And in fact, Quentin doesn’t learn it. (I just learned started the sequel, The Magician King, and Quentin is still looking for a quest to fill the hole in his soul.) And neither do April and Frank Wheeler in Revolutionary Road, for that matter.

And this is the same concern that I have about magic in Paganism. I fear that either it becomes just another technology that contributes to the disenchantment of the world (see Wouter Hanegraaf, “How Magic Survived the Disenchantment of the World”, Religion, vol. 33 (2003)), or else it becomes a form of escapism, another way of avoiding reality. Real magic, I would argue, is never “used”; it is experienced. And that, I think, will be the subject of a future post.