|

|

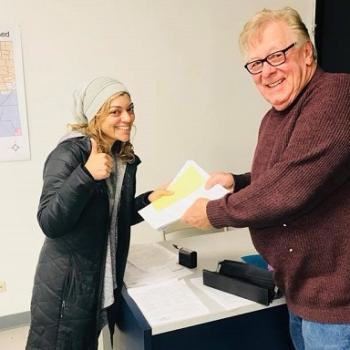

Been there, done that

|

If you’re looking for a microcosm of European Muslim society, one that exemplifies all the challenges and opportunities faced by immigrants from Muslim countries, The Netherlands may not immediately come to mind. Often overshadowed by the larger Muslim populations in Germany, Britain or France, The Netherlands has been the home of a number of personalities hostile to Islam and Muslims, including right wing politician Geert Wilders, activist and former MP Ayaan Hirsi Ali, murdered filmmaker Theo Van Gogh – all of whom have stirred up emotions of Muslims far from Europe. At the same time, Muslims in The Netherlands (who are primarily of Turkish origin) have quietly learned from their experiences and have broken barriers in political and social life – often well before counterparts elsewhere in Europe and other Muslim minority countries.

Central to this is Fadime Örgü, one of the first Dutch Muslims elected to Parliament over 10 years ago, serving there with Wilders and Hirsi Ali and providing a counterbalance to the increasingly personality-driven, rightward tilt within the political system. We spoke to Örgü about recent events, including Wilders ban from entering the UK to screen his anti-Islam film Fitna, the new Muslim mayor of Rotterdam, Ahmed Aboutaleb, and her own experiences, both in Parliament and working with Muslim immigrants in the Netherlands and beyond.

![]() First of all, tell us a little bit more about yourself – how you got involved with politics, eventually ending up in the Dutch parliament.

First of all, tell us a little bit more about yourself – how you got involved with politics, eventually ending up in the Dutch parliament.

Fadime Örgü: Well, I started when I was 15. The reason I started so young was that I was finding out a lot of things were not going well in society. I thought I have to take the initiative. I figured out that politics was the place to solve these issues. The Liberal Party in the Netherlands – it’s not the same as in England or America, it’s a centre-right party – asked me to join them. They explained to me that you have to take your own responsibility to change personal, social and political issues. While they were explaining liberalism to me, I thought, “This is me they’re talking about.”

I first started on a local level, setting up a girls group to work for economic independence. I wanted them to go to school, finish their education and then get married, instead of getting married first and not having a good education. If they got divorced, they couldn’t find a job. That’s the way it worked in those years.

At 17-18, I became more active on a political level in the youth sector, getting to know other organisations in the Netherlands and other European countries. I became active in European youth organisations, working on minorities in Western Europe, organising activities for young people. They were all immigrant and minority children. It’s funny seeing how all the minorities in Europe wanted to work together. In that time gays and lesbians considered themselves minorities too. But our organisation was focused on immigrant children from guest workers mainly.

I did that for about 8 years, working with organisations on a European level and some in the Netherlands, but all were linked to politics. You could see that politics were everywhere. You had to be in politics to change the world. By the time I was 21, I said that I’m going to be a Member of Parliament because that’s the place I have to be, because there I can change something. I told my friends that when I become a Member of Parliament, would you like to work for me (Laughs).

![]() Very ambitious.

Very ambitious.

But I never thought that I would do it so young. I thought that you would become a Member of Parliament when you’re older than 40. I never thought that I would do it before the age of 40!

In ‘97, I became a candidate for a member of parliament. The reason I was a candidate was that I wanted to figure out how the structure was working. Finally, I was on the list (to be) elected directly during the election of ’98. Before that time, I was working for the public TV station in the Netherlands, making TV programmes. At the end of ’97, I stopped because (of the) campaign for parliament. By the beginning of ’98, I became Member of Parliament for the Liberal Party.

I was always active in politics anyway. I started from the youth organisation and developed myself in all fields. When I started in parliament, I was the youngest Member of Parliament in my party.

It is a good thing if you are a young Member of Parliament. You have to learn a lot, but at the same time, you have much more energy and you can deal with it.

![]() At the time you were elected to Parliament, I can’t think of any other people from a Muslim background who were elected to high political office…

At the time you were elected to Parliament, I can’t think of any other people from a Muslim background who were elected to high political office…

…I was actually the first in the Turkish community. Here in the Netherlands, the Turkish community is the biggest Muslim community. Together with another colleague from the Social Democrat Party, we were the first ones to get elected. It was huge news, you know. All the Turkish news TV stations and papers were all in the Netherlands to broadcast. Even when I was walking in Istanbul, people recognised me! (Laughs) Even now, in Turkey, if you ask them who was the first (Dutch-Turkish) Member of Parliament, people know my name. One way or another you make history, being the first one.

We also made news because we were both female. In that time, in Turkey, in the whole government, there were probably (only) two women or something like that. Nowadays it is changing rapidly, but in that time it was quite new that women got into parliament, especially so young.

Normally, immigrants who got involved in politics, whatever history you look at, it’s mainly third or fourth generation who get involved in politics. We were both second generation, so for them it was something spectacular.

![]() You came into Parliament at a very interesting time, because in the years you were in Parliament, a number of high profile incidents and people were in the news from the Netherlands, such as the murder of Theo van Gogh, and the rise of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Geert Wilders – who were both in Parliament with you…

You came into Parliament at a very interesting time, because in the years you were in Parliament, a number of high profile incidents and people were in the news from the Netherlands, such as the murder of Theo van Gogh, and the rise of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Geert Wilders – who were both in Parliament with you…

Geert Wilders became a Member of Parliament after me – the same year, but later. Geert Wilders is one of the persons I know very well – he was sitting next to me for over six years. He already started – the first year when he became Member of Parliament – working on the issue of Islam.

This is not a new topic for him. It’s also not something that came out of the blue. Actually, the day that he started in Parliament, this was one of the topics he wanted to deal with. He believed that if we as a party focussed on this topic, we could get more seats. For him, this was the topic and, with this topic, we could run the world.

At the same time, he was new and he did not have the experience. He was young and maybe he also did not have the courage to do things by himself. And in those years, he was listening to his colleagues. When I said, “No,” he said, “OK. It’s a no.” He was accepting it and he had to deal with the party discipline anyway, because first you have to convince your own party members, then you can go outside and tell the world what you think. That’s how it works in a party.

So the party couldn’t convince me, for example, of his ideas. Because of that, he never could come out with this topic.

![]() You had a moderating influence from the inside, basically.

You had a moderating influence from the inside, basically.

Yes, at that time, I was one of the persons who – well, I was actually THE person who – in the beginning, said “no” to what he was working for.

In 2002, I was already a Member of Parliament for four years. During that election, a new party came up – the party of Pim Fortuyn. That man was killed in May 2002 by an activist – thank God it was not an immigrant or a Muslim who did that, because that would have been a huge problem in the Netherlands. Because he got killed, (his) party got so many seats, it became the second biggest party in the Netherlands. That government lasted for three months before it collapsed, so we got new elections within a year.

In January 2003, we had those elections, and in those elections, Hirsi Ali came to Parliament. She was from the Social Democrat party at the time and our leader at that time wanted her to be a member of our party. That was the time that everything happened. After 9/11, Europe changed its agenda and the complete atmosphere changed. The topic Islam became the main topic – it was them against us. That was the new politics. Nothing was predictable anymore.

In Europe, and especially in the Netherlands, it was the party programme by which you won elections. This was changing in 2002-2003. After Pim Fortuyn, the personalities of people in politics became more important. People could vote for the personalities. The one subject parties were getting interested and (so were) the ones that were shouting all the time instead of having solutions. It was a lot of reacting instead of being practical.

That year, (January 2003) our leader, Gerrit Zalm, got Hirsi Ali in the party. The problem was not that she had certain ideas, but that she was not dealing with the party line. She thought, “I got in from the outside and I feel free to do whatever I want to do.” She was not a politician, but she was more an activist. She was not listening to what other party members were telling her.

She had her own agenda and the media was focused on her. The more the media focused on her, she said things and made news, all the time. One of the starting points, after the election but before she gave the oath, in that week she gave an interview to one of the newspapers here, Trouw, (where) she said that the Prophet was perverse and talked about the big struggle of hers. She had to get security after that.

In her interviews, all the time she was shocking people. Bit by bit, step by step. The Muslim community in the Netherlands were not used to discussing these things. Actually, if we look at this now, it was a good way of practising for the Muslim community – how to discuss taboo topics or how to hear things you don’t want to hear. And decide to go to court when necessary.

![]() When Geert Wilders made his film, Fitna, the reaction to that by Muslims in the Netherlands, from what I understand, was quite muted – maybe because of this experience…

When Geert Wilders made his film, Fitna, the reaction to that by Muslims in the Netherlands, from what I understand, was quite muted – maybe because of this experience…

Yes, of course. The Muslim community in the Netherlands dealt with that so professionally. It was actually the Prime Minister who made a mess out of it, and not the Muslim community. Even Geert Wilders gave a compliment to the Muslim community (laughs) … he said (he had) respect for the Muslim community who dealt with this topic like this.

![]() Also, because of the court case he is going through now in the Netherlands and also the UK’s ban on him from entering to screen his film at the House of Parliament…

Also, because of the court case he is going through now in the Netherlands and also the UK’s ban on him from entering to screen his film at the House of Parliament…

…actually, by these kind of incidents, he’s becoming more popular. He’s becoming a scapegoat. That’s what he’s searching and wishing for. He wants people to put him in a scapegoat position so that he can become big because of that. Muslims in the Netherlands already had many years of experience dealing with that topic in society. That you have to debate in this situation and that you have to come with arguments and you have to respect somebody’s opinion in this situation. If you want others to respect your opinion, you have to respect theirs too. You don’t have to agree with them, but come with arguments instead of saying, “You are not allowed to come in.”

![]() That’s the same parallel with Ayaan Hirsi Ali who now, of course, lives in America after leaving the Netherlands in an immigration scandal. I take it there was a similar reaction to her there?

That’s the same parallel with Ayaan Hirsi Ali who now, of course, lives in America after leaving the Netherlands in an immigration scandal. I take it there was a similar reaction to her there?

Her problem was that politics didn’t suit her. She was more of an activist. Geert Wilders was more of a politician. He knows exactly how politics is working.

Geert Wilders didn’t accept the party line and he was out. But that was his plan. He was thrown out of the party but he was going to set up his own party. He wanted to get thrown out because he knew he was not going to get his ideas done in our party because we were not accepting it – I was there, too.

But Hirsi Ali had a completely different position than Geert Wilders had. She came in from another party – she was dropped in our party, where she didn’t know anybody – but she had to make news about her topic and she was dealing with her own personality and her problems with her Muslim community. She was a refugee in the Netherlands, circumcised as a female. So her personality and the Islam was her topic.

As I said, at that time, personalities in politics became more important after 2002. This was actually a plan of our former leader, to get more votes by using her personality. It didn’t work out at the end Hirsi Ali left. She had to leave because she didn’t fit in the system.

![]() I wanted to get your thoughts on Ahmed Aboutaleb, the new (Muslim) mayor of Rotterdam, one of the largest cities in the Netherlands. How has this been seen, both by Muslims and non-Muslims in the context of the Hirsi Alis and the Geert Wilders?

I wanted to get your thoughts on Ahmed Aboutaleb, the new (Muslim) mayor of Rotterdam, one of the largest cities in the Netherlands. How has this been seen, both by Muslims and non-Muslims in the context of the Hirsi Alis and the Geert Wilders?

Before I answer that, I want to say something about the context in the Netherlands. Since 1985, immigrant residents were given the right to vote and get elected at a local level – even without citizenship. Because of that, we have so many people who are active on local levels. For example, here in the Netherlands, we have more than 100 people with a Turkish background who are city councillors. It’s really a huge amount.

In the city where Aboutaleb became mayor, we have two aldermans of Turkish origin. Nearly 50% of the population of Rotterdam is of an immigrant background. If we had elections in Rotterdam, a person like Ahmed would have been elected anyway. Because of that, they made a good choice to put him in that position, (since) mayors are not elected in the Netherlands, they are appointed.

In the future, the plan is that mayors are going to be elected, but that could take 20 years.

![]() Is this being exploited by people who are suspicious of Muslims?

Is this being exploited by people who are suspicious of Muslims?

Yes, of course. Geert Wilders is exaggerating… he is actually making fun of himself by exaggerating. People who are voting for him are not actually thinking the way Geert Wilders is thinking himself or how he is presenting himself to the media. Most of those people who are voting for him are unhappy with society and they do not trust the government. Especially in bigger cities, like Rotterdam, we have people who have huge housing and employment problems. At the same time, we see people coming from different countries, the surroundings are changing, the street scene is changing, and they can’t accept that. They want to have the streets as they used to look like.

So that group is voting for him, not because they are experts on Islam or they have a certain hatred towards Islam, but they have a prejudice and feeling of racism towards a group that is not familiar to them. Geert’s way of politics is getting all kinds of people who are unhappy in society. And he is trying to tell them that the reason (they) are not happy is because Muslim society is getting bigger and bigger and getting Members of Parliament and becoming mayors in bigger cities and are now ruling our country.

![]() You’ve now left Parliament… are there other Muslims who are entering Parliament and taking up what you’ve done? And what are your plans now that you’ve left?

You’ve now left Parliament… are there other Muslims who are entering Parliament and taking up what you’ve done? And what are your plans now that you’ve left?

In my party, no. Sometimes you hope that people will come behind you who can fulfil that same seat. That didn’t happen in our party, the Liberal Party, we don’t have people with my background who have that position right now.

But I’m not out of the party. I always said that I was going to do this for two terms. After being more than eight years in Parliament you should do something else.

Politics, I can’t leave it. The party invites me (to meetings) and I’m involved with the party structure, working on our program. It’s like an addiction, you can’t leave it. But in my life now, I want to work for my own company.

![]() I hear you.

I hear you.

Later, I can always join in one way or the other in the structures again to do something.

Actually, Zahed, what I’m trying to do is to be in a position that none of the Muslims are getting. Being there, I can change their minds, I can change their views, and I can change their way of vision and ideology.

For example, I am at the board of the Swimming Federation in the Netherlands. Swimming is one of the main sports that we have. We are one of the best in the world. But although we have had 40 years of immigration to this society, we don’t have immigrant swimmers who are representing the Netherlands because they’re not familiar with it. So what I did a few years ago, I got money from the government and now we have 35 organizations in the Netherlands who are going to train immigrant youngsters, from amateurs to professionals. It means that in 10 or 15 years, we will also have a Fatima or an Ahmed who is going to be representing the Netherlands in worldwide swimming.

![]() So I take it you’re optimistic about life in the Netherlands in the future?

So I take it you’re optimistic about life in the Netherlands in the future?

I’m an optimistic person, whatever happens, I feel that we have to learn from our mistakes and that we have to take our own responsibilities. Then, at the end, we will succeed. I think the Netherlands is one of the examples in Europe where you can analyze through the Muslim community all the developments that this community goes through. This methodology is like my life experience.

I’m not saying that by just having a mayor or being a Member of Parliament that we are there. But at least we have examples and we have role models and the youngsters now can say, “I can do it, too.”

Zahed Amanullah is associate editor of altmuslim.com. He is based in London, England.