When television portrays the war on terrorism, more than 67 percent of the time, the enemy is white, according to a recent study by the Norman Lear Center at USC. At first glance this seems odd. Isn’t the war on terror a war against extremist Muslims? Aren’t Muslims mostly brown-skinned?

The war on terrorism, both on television, and in real life, defies our immediate assumptions. The

Washington Post recently revealed that a Muslim convert is heading up the CIA’s counter terrorism unit and that this person (his identity is anonymous) was instrumental in hunting down Osama

bin-Laden.

But, in our popular imagination, we don’t like our enemies to be complex, and the genre of terrorism television knows this all too well.

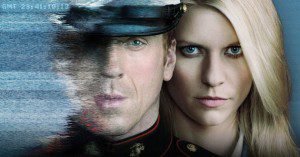

The grandiose black-and-white good vs. evil plot lines seem to hit a more visceral tone. But the latest hit TV series on terrorism, Showtime’s Homeland, presents a picture of terrorism and the role of Islam within the war on terror that not only feels like it’s lifting from the daily news feed, but it taps into the complexity of our present moment, urging us to look deeply at who our enemy really is.

At first glance, the show’s story line seems difficult to base an entire series around: A Marine returns home, traumatized after being held captive for eight years in Iraq by an Al Qaeda cell, only to be faced with the pressure of serving as the poster boy for military heroism. Sargent Nick Brody (played by Damian Lewis) is deeply conflicted about his time in Iraq, and for half the first season he is surveilled by CIA Agent Carrie Matheson (played by Claire Danes) and her mentor at the CIA, Saul Berenson, played by Mandy Patinkin. Following an insider tip and a whole lot of intuition, Mattheson goes to any length to prove that Brody is not the war hero celebrity the media is making him out to be, but has actually been secretly turned to Al Qaeda’s ideology while in captivity in Iraq.

Mattheson suffers from a mental disorder, which she keeps secret to the CIA, and blames herself for 9/11. Since returning from Iraq, where she was also traumatized, her singular obsession is to take down Abu

Nazir, Al Qaeda’s most elusive international terrorist. Like her television predecessor Keifer Sutherland’s Jack Bauer in 24, Mattheson is forced to cross ethical lines frequently. But her superiors support her cowboy ways, earning her the ability to almost mystically predict Abu Nazir’s next move. The implicit message of both Homeland and 24 (which earned its stripes as the quintessential post-9/11 terrorism fighting show) is thus similar: Only through transgressing the institutional inertia of the status quo and going above the law, can the bad guys be brought to justice in the war on terror.

The creators and co-producers of Homeland, Howard Gordon and Alex Gansa, have based the show off of an Israeli series Hatufim (English translation: Abducted), created by Gideon Raff. Gordon also produced “24.” But of course, the genre that Homeland taps into goes back much farther than 24. The real origin of Homeland is in the Cold War era film, The Manchurian Candidate, where an American veteran of the Korean War returns home having been brainwashed and subconsciously lured into serving as a secret puppet of the Communists.

Although, as Lewis points out in a recent interview, Homeland is different than The Manchurian Candidate in one primary way: Sargent Brody is not “brainwashed” by the enemy and is in continuously conflicted and ambivalent about his allegiance to Abu Nazir and Al Qaeda.

Homeland revolves around two points of tension: Has Abu Nazir really turned Brody to his cause while he was in captivity, or are Mattheson’s premonitions totally off base?

The second point of tension revolves around Brody’s conversion to Islam. Lewis claims that Brody’s conversion to Islam serves as the most important detail of the show. In the same interview as cited above, Lewis commented: “In a time of need, I had actually chosen to be a Muslim. We did discuss the immediate assumptions about that: ‘Oh my God, this guy wants to blow us up. Why else would a Marine have converted?’”

The second point of tension revolves around Brody’s conversion to Islam. Lewis claims that Brody’s conversion to Islam serves as the most important detail of the show. In the same interview as cited above, Lewis commented: “In a time of need, I had actually chosen to be a Muslim. We did discuss the immediate assumptions about that: ‘Oh my God, this guy wants to blow us up. Why else would a Marine have converted?’”

Yet Homeland mostly separates Brody’s conversion to Islam from Abu Nazir’s wicked Al Qaeda ideology. By presenting another religious minority through the lapsed Jewish character of Saul Berenson, the show throws even more grey matter into the religious dimension to terrorism. When Brody admits to Carrie that he has converted to Islam, he says, “Well, they didn’t have many Bibles over there. Don’t you think you’d turn to religion if you had to face what I faced?”

All of this goes to imply that the writers desired to make a clear point: Islam is not necessarily synonymous with terrorism. This nuance defies counter terrorism theories such as the conveyor belt theory of radicalization that argues identification with Islam solidifies ones commitment to the radical cause.

Another major facet of our conventional understanding of the war on terrorism is challenged in Homeland, and this point may be the most significant and radical of all. The ideology of the enemy is not a monochrome, black-and-white view of the world. Abu Nazir is almost made into a human at times. Like bin Laden, Nazir favors large scale attacks and dramatic acts of terror, yet by the end of season one, we are left to assume that part of his strategy with Brody (we learn that Brody is indeed working for Nazir by the end of season one) is to infiltrate the inner halls of power by propping Brody up to serve as a congressman. This represents not simply a desire to extinguish all Americans wherever you find them, but a long term strategy.

Nazir’s character represents a post Osama bin Laden Al Qaeda. He is one part Anwar Awlaki, in his understanding of American culture, and one part Osama bin Laden in his grandiosity of acts and smooth operational leadership. We see him largely through the gaze of Sargent Brody, and we find that Brody’s primary motivation for following Nazir is because he witnessed the murder of Nazir’s son, Iesa (Arabic

for Jesus). Iesa’s murder by secret drone strike serves as the primary motivation for Brody’s allegiance to Nazir. This sounds all too familiar, think the Times Square bomber, Faizal Shahazad, who admitted to being radicalized in large part out of anger and frustration over drone strikes that were killing

Muslims in South Asia.

Brody cites the strike on Iesa’s school, which he witnessed, as the primary motivation for his failed suicide mission in the last episode of season one. His horror over the memory of the attack recurs in nightmares, and Nazir exploits Brody’s anger over the cover up of the attack that killed his son Iesa. No one knows about the attack, and somehow Nazir and Brody know that the vice president is responsible for keeping it secret, which is why he becomes their primary target.

Brody is thus painted more as a political radical than a religious zealot. With this crucial nuance, the writers of Homeland have hit on one of the more neglected truths of radicalization in the name of Islam — that is most often looks more like a political movement than a religious movement. This is a change in the framing of the enemy that challenges us to re-conceptualize the nature of this enemy and the deep

internal motivations behind terrorism.

Beyond Brody’s temptation with the cause of Nazir and the pain over Iesa’s death, we discover an even deeper driver to his radical cause in the second to last episode. In prep for a major act that is revealed in the last episode, Brody brings the family to Gettysburg, where he recounts in passionate detail the heroism of an everyday high school teacher who led his men into a suicide charge on the enemy, which turned the favor of the Union forces in the larger battle. Channeling such an iconic American battle as

Gettysburg for the cause of Al Qaeda seems far-fetched, but the writers are up to something more than that.

The implicit message presented is that the modern warrior lacks access to an authentic cause that he can attach his desire for something greater than himself to. Critics might call this relativistic, as in, how can

one ever find the cause of Al Qaeda just, but I think that misses a more complex point. Brody’s battle is also within. Homeland resonates with all of us because Brody is a lot like all of us, searching for something bigger than ourselves.

Like Plato reminds us, we must be careful out there, because everyone we meet is fighting a hard battle.

A version of this article appeared on Huffington Post.

Daniel Tutt is an activist, writer, and Ph.D. candidate in philosophy and communication at the European Graduate School. His research and activism concentrates on Muslims in America, Islamophobia, and inter-religious dialogue. In philosophy, he works in the continental and psychoanalytic traditions where his work looks at ethics and political theory