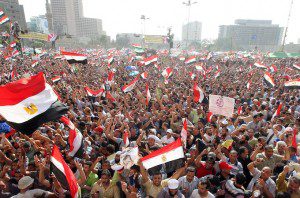

In the 18 months since February 11, 2011, the military has squandered almost all of the goodwill that remained with the Egyptian people. True, some still support the military, either because they’re part of the economic elite, the bloated security system, or are tied to both through patronage networks. The plight of Coptic Christians, who fear Islamist power even more than a government that has massacred them with impunity, is even more tragic.

But for most Egyptians, the constitutional coup d’etat that dissolved parliament and curtailed the incoming president’s power was a coup de grace that ended any pretence of military support for the people. No Egyptian with a political pulse today believes the army is interested in anything more than preserving its economic and political dominance in the new era.

For its part, the Muslim Brotherhood played a minimal role in the revolutionary protests that brought down Mubarak. But it dominated the transitional period, winning the largest share of seats in the now disbanded parliament – and today the presidency.

Despite the electoral victories, the Brotherhood has manoeuvred itself into a position as untenable long term as the military’s. Months of barely clandestine negotiations between the Brotherhood and SCAF over how to divide post-revolutionary power (which continued even as SCAF eviscerated the constitution), coupled with the leadership’s lack of serious criticism for mass arrests, military trials and violence against protesters, cast a long shadow over its integrity and commitment to democracy.

Now a wide swathe of the Egyptian public – not just revolutionary activists, but also the Brotherhood’s conservative base – believes it sold out a revolution in which it was never vested for a greater share of power. This helps account for the surprisingly strong showing of Salafi candidates in the elections, as well the sometimes dramatic exit of younger Brotherhood activists from the movement since February 2011.

Mohammed Morsi now will assume a Presidency with limited powers while being viewed with great suspicion by much of the Egyptian populace.

Few ways to reestablish credibility

The only way for SCAF or the Brotherhood to reestablish credibility is to markedly improve the lives of the tens of millions of Egyptians who live in grinding poverty, scraping by on $2 a day or less. Yet there is almost no possibility of effecting such a radical economic transformation.

The military’s enormous economic power is directly tied to the existing system, while the Brotherhood leadership is ideologically committed to neoliberal policies that perpetuate inequality. Even if its leadership wanted to challenge the gross imbalances that define Egyptian society, the military and economic elite more broadly will fight tooth and nail to preserve their dominance.

Ultimately, there is little chance that whoever governs Egypt in the coming years will significantly improve Egyptians’ lives. The existing power structure is too entrenched, the global economy too weak, and Egypt’s relative economic and strategic position too unfavourable to enable anything close to a “Turkish miracle” that everyone hopes for, and which is the only chance either political force has to regain its squandered legitimacy.

More likely is continued stagnation, government mismanagement of reforms, and ongoing state oppression and brutality that will serve as a constant reminder to Egyptians that both SCAF and the Brotherhood are unwilling and incapable of working for the interests for society as a whole.

An path forward for revolutionary forces

In the meantime, experienced activists at the centre of the revolution’s first phase have not invested all their chips in the current political process. Taking a page from the Brotherhood’s playbook, they’ve gone out to poor and conservative working-class communities across Egypt and begun the arduous but all-important task of building relations and trust. Had the transition process been seemingly cleaner, and revolutionary forces achieved a share of power, it would have been very difficult to avoid becoming a fig leaf for the consolidation of a system that would remain rigged against them on every major political, social and (especially) economic issue facing Egypt.

Excluding them from the emerging political system (which was helped by several freshman mistakes by the revolutionaries, such as trusting the military during the crucial first post-Mubarak months or fielding multiple presidential candidates who drained votes from each other), was the greatest gift SCAF and the Brotherhood could have given the revolution.

Now the country’s progressive forces can spend their time building an opposition that is rooted in society and can effectively challenge the political lies and illusionary narratives that will be liberally dispensed by the old/new system to pacify the masses. Equally important, they can develop a narrative for the future that the majority of Egyptians can believe has a chance of being realised, rather than leading to the chaos and instability that the military has constantly warned them would come with any attempt to radically change the structures and relations of power governing Egyptian society.

Of course, this grassroots strategy will take years to take hold, and will come up against the interests of the patronage and power networks of the Brotherhood and the military. And before anything can happen, the thousands of progressive activists who’ve fallen into a funk in the past few months need to “get off the couch, stop complaining” and get back to work, as one young activist leader wrote on his Facebook page yesterday.

But if the incompetent performance of SCAF, the Brotherhood and the rest of Egypt’s power elite is any indication, there will be plenty of opportunities for Egypt’s revolutionary forces to lay the foundation for a powerful opposition movement that will have a fighting chance to win real power the next time Egyptians head to the polls.

This is the best any revolutionary movement can hope for less than two years into a struggle which, if history is any guide, will take decades to decide.

Mark Levine is professor of Middle Eastern history at UC Irvine, and distinguished visiting professor at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden and the author of the forthcoming book about the revolutions in the Arab world, “The Five Year Old Who Toppled a Pharaoh. This article originally appeared in Al Jazeera.