Why are some in Turkey discussing what Islam’s sources should be? After all, Islam has been around for quite some time, and millions of Muslims are seemingly content with the way they understand and practice it. Yet, Quranists–a Turkish Muslim group critical of hadiths (believed-to-be sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), Islamic sects and many traditional teachings within Islam–do not buy into the popularity of traditional Islam.

Although questioning the authority of hadiths at least dates back to ninth century Mu’tazila thinker Nazzam, historically the orthodox view regards hadiths as the second most important source of Islam. Today, similar views are embraced by Muslims in many areas of the world, including Malaysia, India and the United States, although Turkish Quranists have no organic links to them.

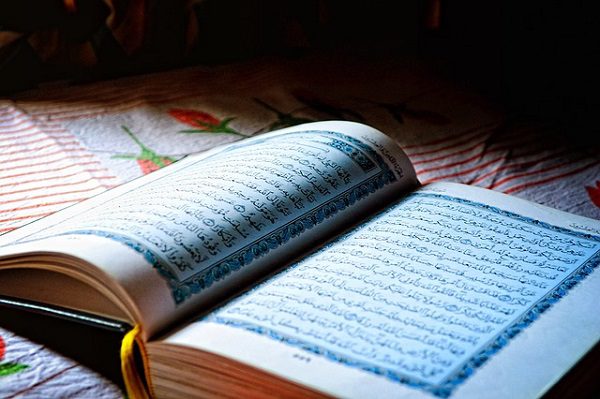

Quranists call for a new interpretation of Islam, which they believe is possible by being critical of hadiths while restoring authority of the Quran in Islam. This, they argue, is not reformist, but marks a return to a more authentic Islam.

These discussions were rekindled a few weeks ago, following a Friday sermon by the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) that denounced Quranists. Diyanet referred to a hadith collected by the hadith scholar Tirmizi, where the Prophet allegedly warned Muslims about people who would ignorantly assert that Quran is their only guide.

Despite the sermon’s circularity–defending the authority of hadiths by referencing a hadith–Diyanet’s reasoning was immediately embraced within traditional Islamist circles.They further questioned the authenticity and sincerity of Quranists’ claims and accused the movement of serving orientalist ends.

Unlike Diyanet, Quranists lack TV and radio channels, a massive share of the state budget (approximately two billion dollars) and thousands of imams advocating their interpretation of Islam throughout Turkey. Thus, they have a hard time responding to allegations made by traditionalists. The most effective way Quranists have made their case so far has been social media. Through Facebook and Twitter Quranists are arguing that defending hadith literature is a disservice to Islam and an insult to Prophet Muhammad.

They claim that, as the messenger of God, it is Muhammad’s message that should really matter and that the Prophet’s personal decisions about his life (such as the way he dressed, whether he was bearded, or what he preferred to eat) have no religious significance. Furthermore, Quranists remind their fellow Muslims that the hadiths were collected several centuries after the Prophet and thus are not reliable. Contemporary sects, they argue, primarily owe their genesis to political struggles and power relations within the Muslim community.

To persuade traditional Muslims, Quranists also appeal to inconsistencies within the body of hadith literature as well as contradictions between Quran and hadiths. The latter, in particular, are believed especially persuasive due to the Prophet’s adjuration to adhere to Quranic teachings. However, a more effective strategy is to show that the Quran does not support various controversial traditionalist beliefs and practices. Rajm, the stoning people to death for adultery, is one such practice supported not by the Quran but by hadiths and exercised in Saudi Arabia and Iran in the name of Islam.

Other examples are the murder of homosexuals and the exercise of capital punishment for apostasy, which are exercised by ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Quranists argue that not only do these so-called “Islamic” punishments lack a Quranic mandate, they in fact owe their inception to the influence of the Old Testament on the content of the hadiths.

In response, the spokespersons for traditional Turkish Muslims have accused Quranists of “surrendering to modernity,” in other words, prioritizing modernist judgments over an appreciation of God and all his scriptures. Yet, this seems inaccurate given the Quranist emphasis on Quranic teachings, particularly those that run counter to modernist practices, such as the proscription of alcohol or homosexuality. Ironically, it is even possible to raise the same accusation against traditionalists.

Whilst defending the authority of the hadiths in general, traditionalists often reject particular hadiths. Diyanet, for instance, rejects those hadiths that command capital punishment for apostasy. Lacking any consistent and sound method, Quranists argue that Diyanet’s and other traditionalists’ rejection of particular hadiths are arbitrary and guided by modernist pressures.

Discussion over the authority of non-Quranic Islamic sources dates back to the early period of Islamic history. Mutazila thinkers of the eighth and ninth centuries, for instance, resorted to “reason” to evaluate the authenticity of hadiths. Since then, though unorthodox, Quranist views have persisted.

Two recent developments have led to the resurgence of Quranism. First, the rise of radical Islamic movements and the implementation of certain hadiths by radicals like ISIS, have led some Muslims to question traditionally accepted sources of Islam. Second, the growth of social media has enabled Muslims encounter and share heterodox views more easily. Despite these two factors, Quranists still are not overtaking traditional interpretations of Islam any time soon. But, they seem to put enough pressure upon traditionalists to reevaluate written sources besides the Quran.