By Azza Altiraifi

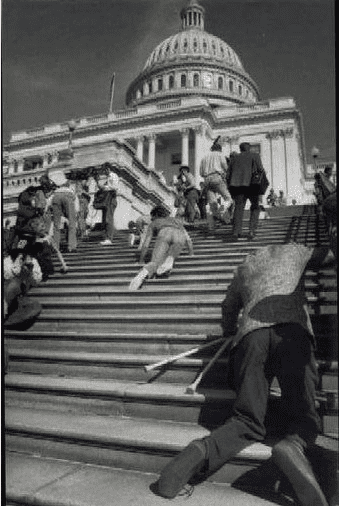

The summer of 2018 marks 28 years since the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which mandated the elimination of discrimination against people with disabilities. It is also a reminder of the sacrifices borne by those who literally crawled up the steps of the Capitol to demand the passage of the ADA. This is the legacy of resistance we carry today.

Yet, its promise has never been fully realized and its shortcomings have been exploited to further entrench ableist policies that target and exclude disabled people at every turn. As the Trump administration ramps up its attacks on marginalized communities of all kinds — including the disability community — the need for cross-movement building has never been more urgent.

Why is it, then, that progressive movements for collective liberation, including anti-Islamophobia movements, have yet to integrate a disability justice lens to their calls for freedom and equality?

I am a Black, Afro-Arab, disabled Muslim woman. I would not have been able to complete my college education, secure a job nor receive the accommodations I rely on to live independently without the protections of the ADA and model legislation that followed it.

Consider these facts: Disabled people constitute the world’s largest minority, with 1 in 5 people in the U.S. identifying as disabled. Every progressive cause is necessarily a disability justice issue, because there are disabled people in every community. Further, ableism, the system that dehumanizes and oppresses people on the basis of presumed or actual disability, is weaponized in conjunction with white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy and capitalism to marginalize and target people deemed unable to produce and therefore disposable and a burden to society.

Given this, any meaningful attempt to disrupt and dismantle white supremacy must necessarily be anti-ableist and anti-capitalist in its framework. However, anti-Islamophobia organizing spaces continue to erase their marginalized disabled membership. Disability is mentioned only in fetishizing campaigns designed to play on people’s infantilizing and ableist views in an effort to score support and sympathy for our cause.

Most recently, this included the outcry over a young Yemeni girl with cerebral palsy who was initially denied entry to the U.S. due to the Muslim Ban. This approach is not only dangerous, it is violent. Disabled people are fully complex beings whose narratives and needs should be a permanent feature of all our organizing, not a convenient prop to be called upon only when it’s politically expedient. Perpetuating these narratives is an inherently dehumanizing process that renders disabled people even more vulnerable to state and interpersonal abuse.

Disabled Muslims are often the first victims of structural and institutional Islamophobia. From Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programs that enlist counselors, psychologists and teachers to identify Muslim youth perceived to be “disaffected,” — thus criminalizing disability and mental illness among students — to FBI entrapment plots that target psychiatrically disabled and poor Muslims, to the disproportionate number of disabled people annually murdered by police , to the deportation by default of mentally ill people in ICE detention, to the restrictive immigration policies that bar disabled people from entering the U.S. at all — there is no shortage of examples in which the carceral state has perpetrated structural violence against disabled people, including disabled Muslims.

It is well past time for the Muslim community to recognize that ableism is not the result of ignorance or lack of awareness. Ableism is, along with white supremacy and capitalism, a foundational structure in this country. These oppressive systems depend upon one another, designating specific bodyminds as valuable and others as their violent, deviant and disposable opposites. These systems were designed with the express intention of concentrating wealth and power at the very top.

And, until the Muslim community, and all other faith communities, confront this history and commit to disrupting and ultimately dismantling these structures, we can never secure our collective freedom.

The ADA is 28 years old and yet disabled Muslims such as myself continue to face numerous barriers that limit our ability to live freely, independently and participate fully in our communities and the political process. One glaring example is the religious exemption that frees all religious institutions and places of worship — including mosques — from the ADA requirements to make public spaces accessible.

This is antithetical to the emancipatory principles of universal inclusion our sacred spaces should be committed to. But this has not been challenged or questioned outside of the disability community. Besides effectively cutting off many of us from our religious communities and congregations, this exemption is also a major contributing factor to the disenfranchisement of people with disabilities across the country.

Religious institutions often serve as polling places and host vocational, “know your rights” and other trainings. These institutions have also increasingly served as sanctuary spaces for people who are undocumented. They serve as spaces that work to provide the community services the state has failed to provide — and yet a significant percentage of disabled people are barred entirely from accessing them. This renders disabled people, especially those who are also undocumented and in need of vocational training or in need of safe spaces unable to access them. It cuts us off from our own houses of worship and compromises our spiritual and communal connections with the Creator. It relegates us to the furthest margins of our communities, leaving us vulnerable to exploitation and violence.

When this administration issued each iteration of the Muslim Ban, our communities rallied before courts and at airports chanting “No Ban, No Walls, Sanctuary for All,” decrying the illegality and immorality of targeting people for exclusion on the basis of their faith or ethnicity. We did not, however, decry with the same vigor policies that target disabled persons for exclusion on the basis of the presumed burden they will impose on the state.

When the labor movement rallied to raise the minimum wage nationally, Muslims chanted along in solidarity, citing the sizable percentage of Muslims who live at or below the federal poverty line. Yet where is the outcry over the legal loopholes that continue to allow disabled people to be paid a dollar or less an hour for their labor?

When the Muslim community renewed the calls for permanently shutting down Guantanamo Bay and the end of all torture, we again failed to integrate a disability justice lens — despite the detainees qualifying as disabled and being subject to unspeakable trauma and despite the opportunity to join forces with a concurrent movement by disability rights advocates to stop the legalized torture of disabled children that continues to occur at the Judge Rotenberg Center and other institutions today.

Intersectionality is not just about affirming that our communities are diverse. Intersectionality is a theory of power. It calls upon us to understand that those who live at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities experience compounded and intensified oppression. It means that people who live at these intersections are far likelier to be victims of interpersonal and state violence.

It is therefore not enough to acknowledge disabled Muslims and our right to live. It is not enough to invite us into your spaces. We must amplify and center the narratives and needs of disabled Muslims, especially disabled Muslims who live at the nexus of other marginalized identities. We must be given leadership roles in our movements and in our sacred spaces. We do this because our faith calls upon us to establish and bear witness to justice, even when it is against ourselves.

We do this because a radically accessible world is one that is better for everybody, disabled or not. Consider how much harder navigating public spaces would be for everyone if curb cuts, elevators, captions, and ramps did not exist. Assistive devices that make things possible for disabled people, make things easier for non-disabled persons too.

I feel deeply the urgency that today’s political climate has generated across our movements. Yet our single-issue organizing spaces have historically failed to account for the needs of those of us who are also oppressed along axes other than the one such spaces are focused on. Do not tell me you are building towards a future of justice and equality when disabled people cannot even enter the room.

Do not claim to speak for all Muslims when your leadership does not reflect the diversity of our vibrant communities. It has been 28 years since the ADA was signed into law. Our community has had enough notice. Disabled people deserve a seat at the table. And I will continue to echo the call of disability justice advocates globally, until we are heard: Nothing about us, without us.

Azza Altiraifi is an award-winning speaker, educator and disability justice advocate. She currently serves as an organizer with the Justice for Muslims Collective in the Washington, DC metro area.