THIS IS A BOOK THAT CAN TEACH US ALL.

THIS IS A BOOK THAT CAN TEACH US ALL.

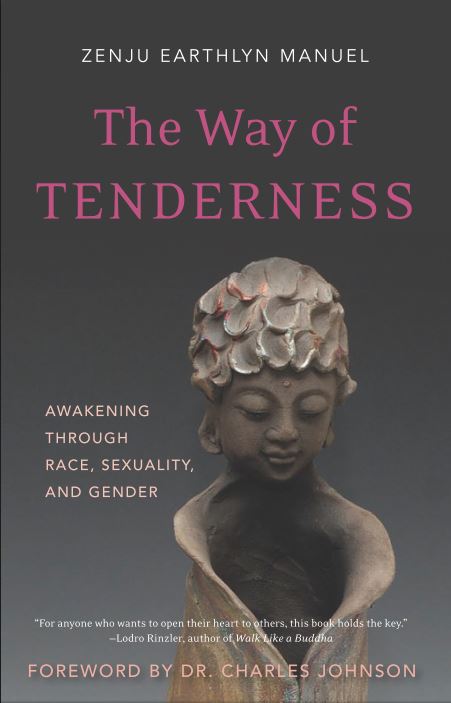

These words grace the back cover of The Way of Tenderness: Awakening Through Race, Sexuality and Gender.

And Tanya McGinnity of Full Contact Enlightenment put it equally well when she wrote:

“This book by Zenju Earthlyn Manuel is essential reading for all Buddhists. Essential.”

Both statements are absolutely true.

As are the several lines of advanced praise in the book’s opening pages, from American Buddhist greats including Jan Willis, author of Dreaming Me: Black, Baptist, and Buddhist, Lodro Rinzler, author of Walk Like a Buddha (and The Buddha Walks into a Bar, reviewed here), Zenshin Florence Caplow, coauthor of The Hidden Lamp: Stories from Twenty-Five Centuries of Awakened Women, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, author of Training in Compassion, Larry Yang, core teacher at the East Bay Meditation Center, and M. LaVora Perry, author of Taneesha Never Disparaging.

With that list of recommendations, and the forward by African-American scholar and philosopher, Charles Johnson, we can rest assured that we are in for a challenging and transformative experience.

And transformative it is. Manuel turns out to be many things and many people, a living example of the intersectionality at the heart of contemporary progressive thought. The first of those that will become apparent to the reader is that she is a captivating writer. In her first sentence she tells us: “I was hungry when I attended my first Nichiren Buddhist meeting in 1988.” And that paragraph concludes, “The truth is I was too ashamed to tell them that I chanted because of a deep pain that I could not name.”

Who hasn’t been hungry or felt ashamed of a pain that could be felt but not known or understood?

In her case, she tells us, the hunger was literal: she didn’t want to go chant, she wanted to eat. And this too is so often our own condition, distracted by the desires of the body or mind. If we find a place for transformation, it’s almost as if it is by accident, against our will, against the stream of our ego and our habits.

The next person who emerges from the pages is a person deeply aware of the oppression of our society, an oppression based on structures of race, sexuality, gender, and class.

In the very next paragraph this person, we might call her the social activist, meets the Zen priest:

Oppression is a distortion of our true nature. It disconnects us from the earth and from each other. Awakening from the distortion of oppression begins with tenderness: we recognize our own wounded tenderness, which develops into the tenderness of vulnerability and culminates in the tenderness that comes with heartfelt and authentic liberation.

Through the book other voices emerge as well: the academic, the philosopher, the voice of rage, the seeker of justice. All of these come out in a dance between the absolute: all is one, labels are constructs, and identity is to be transcended, and the relative: we are different, labels are real and shape every aspect of our lives, and identity is who we are. This dance can be described no better than in her own words:

It was clear at the beginning of my exploration that I had been hardened by the physical violence leveled against me as a young child and by the poverty with which my parents had to struggle as Louisiana migrants raising three daughters in the wilds of Los Angeles. I had been hurt as a child when I discovered that others saw my dark body as ugly. And as I aged and moved from romantic relationships with men, I lived in fear of being annihilated for taking a woman as a lover and partner in life. I had grown bound to feelings of injustice, rage, and resentment. I held my life tight in my chest, and my body ached with its pain for many years.

And later on the same page:

I listened to Zen teachers address suffering with Buddha’s teachings. I listened for what might help me to face rage and to develop a liberated tenderness. Some suggested that if I “just dropped the labels” I would “be liberated.” Some said, “We are delusional; there is no self.” Others said, “We are attached to some idea of ourselves.” If I could “just let go of being this and that, my life would be freed from pain.” I thought for a time that perhaps I was holding on to my identity too tightly. Perhaps, I thought, if I “empty” my mind the pain in my heart will dissolve. What I found is that flat, simplified, and diluted ideas could not shake me from my pain. I needed to bring the validity of my unique, individual, and collective background to the practice of Dharma. “I am not invisible!” I wanted to shout.

That is exactly what the book turns out to be: an exploration and validation of her unique, individual, and collective background brought to and through the Dharma, a set of teachings that so often (too often?) point us away from our own concrete, lived reality toward a non-individuated, faceless, genderless, classless, colorless absolute.

~

Again and again, Manuel draws in Buddhist teachings, which often are abstract and universal, and brings them back down to the reality of lived daily existence. Again, she uses her own experience as the material out of which to shape the book, but she writes in a way that invites each reader to bring in their own concrete reality, to examine it, and to move toward the way of tenderness. This way of tenderness cannot be taught or trained or practiced, she writes, but instead:

simply rises up as an experience void of hatred—for oneself or otherwise. As a matter of fact, I can barely write about it. Still, I feel compelled to speak of what is in my bones for the sake of bringing back the connectedness we are all born with.

In the book, Manuel’s eye is always on this absolute quality of Buddhism, described as “tenderness” which itself evokes the relative, the lived, the bodily nature of our lives. Writing about the body, and one of the sentences I find most compelling and central to the book, Manuel says, “If the body can withstand the arising and ceasing of pain and suffering, there is no need to transcend it. We need to transcend, instead, our belief that spirituality does not include the body.” This is directly opposed to what many have rightly described as “spiritual bypassing” by so many people in Western Buddhist and spiritual circles, the attempt to just jump to the goal and ignore the messy reality of this body and its relations to the world.

~

The next chapter, “Multiplicity in Oneness,” speaks again directly to the confrontations of identity and transcendence, and the importance of identity and place and being seen that people who are oppressed experience. Manuel writes there about the complicated lessons of “how to be an ally” – lessons many of us find ourselves learning again and again. We read there about the biological myths, “stories created about certain groups of people that lack accurate historical perspective or content” that give rise to bigotry, supremacy, hatred, and oppression. The path to true ally-ship comes, we learn, through friendship and an intimacy out of which differences can be acknowledged and explored.

In the next chapter, “Body as Nature,” the continental philosopher side of Manuel emerges. It begins, as does all good continental philosophy, with an awareness of death. Death returns us to our mortal body, the locus of all we know. She quotes the great French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “We know not through our intellect but through our experience.” Later in the chapter Manuel draws from the French/Martinique-Algerian philosopher Franz Fanon who tells us that our bodies are our “lived sites of meaning.”

We cannot help but recall the Buddha’s own call for us to seek liberation in this very body:

I do not say that there is a world’s end to be known or seen or reached where one is not born, does not age or die or pass on or reappear. Yet I do not say that suffering can be ended without reaching the world’s end. Moreover, I declare the world, the arising of the world, the cessation of the world, and the way leading to the cessation of the world to be in this very fathom-long carcase with its perception and its mind.

Never can the world’s end/Be reached by travel,

But there is no escape from pain/Without reaching the world’s end.SN I, 62. (from p.68 of Richard Gombrich’s What the Buddha Thought)

However, such abstract teachings are lost if not brought back to the particular lived realities of the practitioner and Manuel sweeps us back into her world (our world, in terms of shared space and time) through African-American philosopher George Yancy’s work Black Bodies, White Gazes, which “reminds us that our bodies are socially constituted within a lived history and a lived experience.”

In the body’s experience comes suffering, different for each of us as we navigate life, ever seeking in our own (often dysfunctional) ways to escape that suffering. Manuel writes of a meeting with a Zen teacher, pouring out her problems to the teacher. His response was a smile and a reminder “that life includes everything, even the ‘bad,’ and that … a desire for a life without problems was a desire to live a life of fantasy.” The same is true of our intimate relationships, she says. As a relationship coach tells her, “relationships [must] provide enough intimacy to create the friction needed for … liberation. [Those] in which we seek only peace and quiet end up dying.”

Often these problems become us, they become our stories. Drawing from bell hooks, Manuel reminds us that sometimes these stories are put upon us by society, as in the case of the media’s “constant depiction of violence against women, black men, or queer folk” creating “an expectation of or permission for brutality against and between particular people off screen.” But rather than fixating upon this aspect of identity projected on her by society, Manuel turns to Pema Chödrön for the reminder that our “identities are fluid and dynamic.” And this fluidity is both a source of tension and discomfort within us and the fact that allows for transformation.

~

In her final chapter, “There Are No Monsters,” Manuel again ruminates over death, but this time not as a reminder of change in life, but as a reminder to love and be heard.

“I regret not having loved enough.” This is a common line I’ve heard reported as wisdom typically delivered by a person on the verge of death. I await the moment when the deep regret about remaining silent about issues of race, sexuality, and gender rises in our hearts, and we understand what that means in terms of the systematic withholding of love from those who are different from us, then we truly come to regret not having loved enough.

“Death,” she continues, “whether our own or others, can be a powerful gateway to complete tenderness… I came to see that the great matter of death is not great because it’s scary but because it is profound in its immense capacity to arouse a loving nature within us.”

~

As a reviewer I find myself struggling to do justice to even small parts of the book, let alone the work as a whole. It would be easy to compare her work to one from Pema Chödrön, another amazing Western Buddhist teacher and writer. But her work goes further than Chödrön’s precisely because of the life she has led. She has lived the oppression exercised on black people, women, and the LGBTIQ community and in this book she holds all of that up so perfectly like a mirror to the reader.

While it certainly is a book that should be read by all Buddhists, I would also recommend it, specifically the chapter “Body as Nature” to anyone interested in Buddhist Philosophy, especially in conjunction with continental thinkers like Merleau-Ponty.

Rev. Zenju Earthlyn Manuel, PhD, author, visual artist, drummer, and Zen Buddhist priest, is the guiding teacher of Still Breathing Zen Community in East Oakland, CA. She was raised with two sisters in Los Angeles after her parents migrated there from Creole Louisiana.

Rev. Zenju Earthlyn Manuel, PhD, author, visual artist, drummer, and Zen Buddhist priest, is the guiding teacher of Still Breathing Zen Community in East Oakland, CA. She was raised with two sisters in Los Angeles after her parents migrated there from Creole Louisiana.