Burma continues to be an enigma in the minds of most Americans today. With a population that is nearly 90% Theravadin Buddhist, many Westerners imagine a land of peace and smiles, ancient pagodas, and silent lines of monks and nuns passing on alms rounds. And while these are real aspects of the country, there is much, much more beneath the surface.

Stanley A. Weiss writes for the Diplomat about recent military-political factors shaping the country, summarized in a report called “Weaponizing U.S. Economic Engagement in Burma.” Weiss writes of the report that, “It has been widely shared across defense and intelligence networks worldwide the past two months, and with good reason: Its warning of a “Burma in crisis” is stark.” (emphasis added) The report goes on to suggest that U.S. policy-makers have been duped into thinking real reform was taking place, while military leaders continue to hold a tight grip on political and economic aspects of the country.

An example of the measured optimism can be found in this 2013 Department of State testimony to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. There you see the positive: new peaceful elections, opposition party winning, revisions of economic and media policies to open; as well as the negative: communal violence and anti-Muslim discrimination in Rakhine State and beyond, ongoing ethnic violence elsewhere in the country, and a constitutional and legal infrastructure still firmly favoring military rule of the country.

However, this new report, written by former commander of the Green Berets, Colonel Tim Heinemann, emphasises a much less optimistic view of the country. He writes, “US government and businesses are being deceived by mischaracterizations of realities past and present in Burma. By the time the rules of this game are figured out, the US public and private sectors will be fully committed on the ground. It will then be too late, as has been the case in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

It is notable that Heinemann warned of problems in Iraq in 2003, a warning that was ignored at the time. Heinemman suggests several steps to avoid the failures of Iraq and Afghanistan, namely focusing on small-scale and ethical businesses and individuals and looking at the younger generation of change-makers who will not so easily succumb to older generation’s prejudices.

On the Buddhist front, Burmese American Buddhists have formed a group called Saddha, releasing a video plea to the world to end violence against the Rohingya last fall. As discussed here in October:

Recounting the facts of the last few months, surveying reports from both within and outside Burma, they say:

Our online and personal interactions have shown us that not many Burmese Buddhists express sympathy towards the Rohingya, even as fellow human beings.

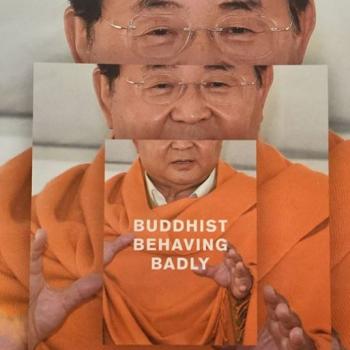

Indeed, this is consistent with numerous reports from within the country, personified by Ashin Wirathu but not limited to him, of regarding the Rohingya, and Muslims more broadly, as “like dogs.” They continue:

The Rohingya have been dehumanized online in Burma as “illegal Bengali immigrants,” terrorists who breed like animals and convert Buddhist women in Rakhine state. …

There are Burmese people who believe the Rohingya’s presence in Burma risks the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Rakhine state and threatens our Buddhist heritage.

Turning to the future of Burmese Buddhism, they express a shared concern, saying that, “we believe that what is happening now will jeopardize Buddhism far more than anything else… today, ‘our’ Buddhism has become the face of inhumanity to the rest of the world.”

Of particular help in Weiss’ article is this description of the ethno-religious political landscape of Burma:

Since most Americans aren’t familiar with the geography of Myanmar, let’s use the U.S. political map to demonstrate what Heinemann is talking about. As we all know, America is blue (referring to Democratic states) on each coast and red (Republican states) across the vast middle of the country. Now, imagine if this divide were even more stark: that there was a continuous belt of blue along both coasts connected by a long blue line across the top of the country, surrounding the red states like a horseshoe. Imagine if everyone in the red states were Christian and Caucasian and everyone in the blue states were people of color and of many different religions. Now, imagine if the vast majority of America’s economic resources were all in the blue states, but that the U.S. government was operated by and for the red states, with an all-powerful and unaccountable U.S. military that constantly exploited the resources of the blue states for its own gain while denying its people basic rights.

Along with this article by Weiss, see Matthew Gindin’s excellent recent discussion in Tricycle Magazine. In that article, Gindin recounts asking, Burmese dissidents and Rohingya survivors about potentials for resistance to the violence there,”The Burmese people at the event said resistance in Burma is very difficult and made rarer by the pervasive brainwashing of the Burmese Buddhist public, who have been largely convinced to regard reports of atrocities against the Rohingya as ‘fake news.'”

Gindin continues, quoting U Kyaw Win, an elder dissident of Burma and friend of Aung San Suu Kyi, “what happened at Dachau and Auschwitz is going on in Burma. It is a slow genocide. It is a way of getting rid of a certain group of people—you can do it quickly or very slowly.”

Another activist, Khin Mai Aung, a New York–based racial justice and immigration rights lawyer, is also quoted, saying, “The country has lived under military control for some time, and it doesn’t have a strong foundation for a civil society. People have difficulty distinguishing fact from state fiction, having lived under military propaganda for so long.”

So, internally the Burmese face government propaganda, sometimes in alignment with opportunistic Buddhist leaders, externally they face either a general lack of information or idealization. The road forward remains thus very uncertain. The growing connections of diasporic Burmese (notably not only Buddhists, but also Hindus, Christians, and Muslims in Gindin’s article) might generate a positive and lasting counterbalance to the military and Chinese and Russian forces who profit from the authoritarian state. But the road to democracy could be a very long one. As Weiss writes:

“Ethnic conflict in Myanmar has changed its dimension,” he tells me, “The young generation of Burmans blames the military and does not seek Burman dominance … we still have a chance to become a nation without internal armed conflict, but it may take another 20 years.”

Support independent coverage of Buddhism by joining a community of fellow learners/practitioners at Patreon.

‘Like’ American Buddhist Perspectives on facebook.