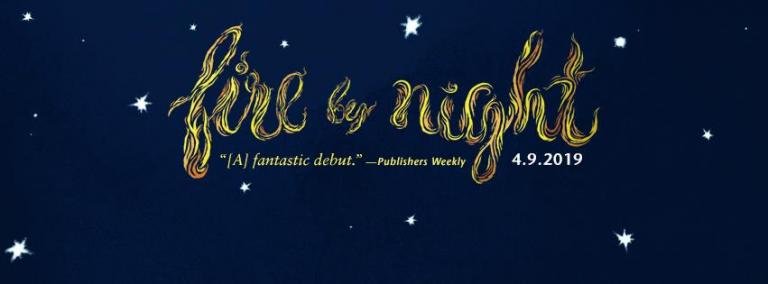

In chapter 2 of Fire by Night: Finding God in the Pages of the Old Testament, Mennonite pastor and author Melissa Florer-Bixler writes about encountering a “God of neighbors” in . . . [checks notes] . . . Leviticus? Leviticus isn’t the first place you’d expect a Mennonite pastor to turn for insights on neighborliness, but Florer-Bixler is not here to reinforce your expectations (read: stereotypes).

Leviticus is a book about holiness. At sundry times and places throughout Christian history, holiness has been understood in terms of separation, purity (in the sense of being uncontaminated), and, yes, even segregation. (Thus, Florer-Bixler recounts receiving flyers from the local KKK using the Holiness Code as a pretense for white supremacy.)

For Florer-Bixler, a breakthrough in her understanding of Leviticus came when she recognized that the book is written to a group of people wandering in a desert before entering the land God promised them, literally depending on God for their survival. She writes,

For ancient Israel, holiness takes on spacial character. Unlike the peoples around them, both the Egyptians of the past and Canaanites of their future, the Hebrew people have God as the only source of holiness. . . . It was the Jewish biblical scholar Jacob Milgrom whose writings helped me learn to explore Leviticus as a set of ritual symbols that tell us something about God’s protection and care for God’s people. (43)

So, while Leviticus does indeed discuss matters of purity, in this chapter Florer-Bixler’s thesis seems to me to be this: “Holiness [is] inseparable from justice” (45). As she writes, “Leviticus teaches us that holiness is more than keeping yourself uncontaminated. Instead, purity is a ritual that embeds justice in the body. . . . Leviticus is a book about getting a people inside of God’s life, and then making a world that looks like God’s justice” (44–45).

Florer-Bixler describes Leviticus as a response to a God who provides. God liberated the people from Egypt; God gave them manna to eat in the desert; and God leads them across the Jordan into the land God promised. And now the people are called to embody God’s life together in community: “In Leviticus there is always enough, the edges of the field full for those who are in need. In God’s life the elderly and the sick are honored and celebrated. In God’s life people who are deaf and physically atypical are treated with dignity” (46).

Rather than trying to apply the specific instructions of the Holiness Code directly to our contemporary life (perhaps by distinguishing between the ceremonial laws and moral laws, for example), Florer-Bixler invites us into “the process of figuring out what God’s life looks like here and now, how to take these word passed down to us and to work them out in the grain of our own lives” (46–47). Doing so means asking ourselves the same kinds of questions the Israelites asked:

What are the idols? Who are my enemies? Where do we see the cornerstone of justice? How does our life echo back those words: “I am the Lord”? What are our failures? How can we scrutinize and talk back to the “common sense” institutions and assumptions of holiness that dictate our social and religious world? Who stands at the margins of dominant power and can lead us in the world of recognizing God’s holiness? (47)

I won’t spoil the whole chapter by recounting how Florer-Bixler personally lives this out in her interactions with her Muslim neighbors, other than to note this interesting insight she discovers:

We find that mixing together, whether it was cattle or seed or textiles, is not anathema in itself. Instead, mixtures are the stuff of holiness. Rather than a violation of an imagined divinely appointed order—as members of the KKK have assumed—mixed things are the holiest, set aside for holy use, made special by being under the auspices of the priests. Interwoven materials and combined metals illuminate the tabernacle and the priestly garments (Exodus 27:1-19, 28:6-8). (50)

Florer-Bixler focuses her reading on Leviticus 19, which offers a version of the 10 Commandments and which she notes is the center of the center of the Torah. Her reading would only be strengthened by turning attention to six chapters later where Leviticus 25 explicitly describes the year of Jubilee and the redemption of the poor and enslaved. Some interpreters have connected this chapter and its Jubilee instructions with Isaiah 61’s vision of the “year of the Lord’s favor,” which Jesus himself quotes in his inaugural sermon in Luke 4. If this interpretation has any merit (which I tend to think it does), then Isaiah and Luke offer intracanonical instances of the kind of reading Florer-Bixler commends: engaging “the process of figuring out what God’s life looks like here and now, how to take these word passed down to us and to work them out in the grain of our own lives.”

For Jesus, following Isaiah, this meant not applying the specific laws of Leviticus 25 in his context—many of which would not make sense outside their original context—but rather displaying how Leviticus 25 reveals a God who is good to the poor, the captives, the blind, and the oppressed. This is the God we find in the pages of the Old Testament—and the God whose life we are called to inhabit in our own time and place.