Note: Last Saturday, July 8, I gave a plenary titled “A Great Cloud of Witnesses: Encountering Exemplars of the Gospel Practice(s) of Peace” at the Ekklesia Project 2023 gathering at Englewood Christian Church in Indianapolis on the theme Peacebuilding: Practicing the Peace the World Cannot Give. The following excerpt is from my introduction. A video of the entire talk should be posted on EP’s YouTube page soon. You can also read a fuller version of my talk in my book with Myles Werntz, A Field Guide to Christian Nonviolence (Baker Academic, 2022).

Becoming a Pacifist

I was three weeks into my first year at a small evangelical college in Northern Indiana when a dorm-mate ducked his head into the public showers to announce that a plane had crashed into one of the World Trade Center towers in New York City.

As a right-wing political junkie at the time, I turned to my RA and quipped, “I got 10 bucks that says it was Osama bin Laden.”

I eventually headed to class, where a TV was rolled into the room so we could watch footage of the crash—and then the second one that confirmed that it was, indeed, a terrorist attack.

In the months that followed, I was an apologist for the war in Afghanistan, though most of my classmates didn’t take much convincing.

My sophomore year, I wrote a term paper in my ethics class titled, “A Critique of Pacifism,” which I submitted to my pacifist ethics professor. He gave it back with a lot of red ink and a recommendation that I read John Howard Yoder’s Politics of Jesus so I would know what the heck I was talking about. I picked up a copy at the local Family Christian Bookstore but couldn’t get through the first chapter with all the discussion of ethical theory, so I put it down for a few years.

I picked it back up while studying at an evangelical seminary in the mid-2000 aughts. The United States was now engaged in not one but two active wars abroad. I had a bit more ethical theory under my belt. And Yoder started making a lot more sense to me—so much so that I moved on from The Politics of Jesus to just about any Yoder book I could get my hands on.

For Christmas 2008, my spouse Andrea bought me about half a dozen of those little Yoder tracts by Herald Press, and I considered it the most thoughtful Christmas present I had ever received.

Then I started reading not just Yoder but everyone who wrote on Yoder. I read essays by Michael Cartwright and John Nugent, among many others. My first published article was a review of three collections of essays on Yoder’s work, which I titled “Inheriting Yoder Faithfully.”

On August 11, 2010, I wrote a letter to Stanley Hauerwas telling him that my dad had died earlier that day and that I had just finished reading his memoir Hannah’s Child, which was helping me through the loss.

That fall I met Glen Stassen at a conference and asked him where I could go to study Yoder’s work. He suggested Baylor to study with Paul Martens and Jonathan Tran, so I applied there on his recommendation and was accepted the following spring (after applying and getting rejected by Therese Lysaught at Marquette the year before—but it all worked out!).

At Baylor, I managed to get through most of my courses by writing papers with topics like “Yoder and Aquinas on war” or “Yoder and Barth on natural theology” or “Yoder and Paul on union with Christ.” (You get the idea.) I even got to be a TA for one of Stassen’s protégés, Reggie Williams.

Then I wrote my dissertation on the relationship among the social ethics of Walter Rauschenbusch, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Yoder, where I essentially argued that Yoder’s ethics was indebted to the former two much more than Hauerwas likes to admit. Jonathan Tran was able to arrange for Hauerwas to sit on my committee. Suffice it to say that Hauerwas wasn’t convinced by my reading, but he had some gracious things to say and didn’t stop me from passing.

An Ekklesia Project Lurker

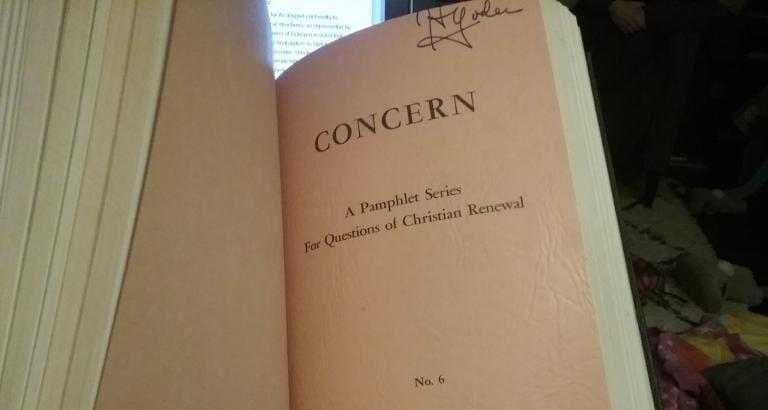

At some point during these years, I became what you might call an Ekklesia Project lurker. I was intrigued by the work you do. I read some of your pamphlets and books. And some of my professors and mentors are full-fledged EP endorsers.

But, until this weekend, for reasons I won’t begin to attempt to justify, I have not personally participated in an EP gathering or event.

Being an EP lurker means a couple of things.

First, it means I received the invitation to speak at this gathering with much fear and trembling. I was, after all, discipled into the way of Christian nonviolence by EP theologians. The list of initial EP endorsers from May 2002 at the end of Hauerwas and Budde’s Subversive Friendship pamphlet reads like a bibliography of my reading list from the late 2000 aughts. What could I possibly have to say about nonviolence to you all who taught me to be nonviolent?

But, second, being an EP lurker means that I have formed certain impressions of EP’s views of nonviolence that may not be entirely accurate—or at least not entirely up-to-date.

Knowing that EP was started by Hauerwas and his colleagues and students has led me to believe that EP’s general approach to nonviolence is what we used to call “Yoderian.”

Or what Yoder himself called “the pacifism of the messianic community.”

Or what Hauerwas would call “ecclesial nonviolence.”

Or what Hauerwas’s detractors would call “ecclesiocentric pacifism.”

Or what advocates of just war who comment casually on pacifism simply call “the Yoder/Hauerwas view.”

This is the view that there is a specific Christological form of pacifism that is embodied in the church and that, by contrast, identifies the violence of the world for what it is.

There are hints of this kind of nonviolence in the subtitle to our gathering: “Practicing the Peace the World Cannot Give” (though I was reminded this weekend that that’s a quote from Jesus, so you’re in good company).

This is the kind of nonviolence that John Nugent calls “Shalom A,” as Philip Kenneson discussed in our opening session.

And it is the kind of nonviolence that was deeply formative for me. It provided an off-ramp for me from the right-wing, militaristic evangelicalism of my upbringing. I believe that there is much to be said for this kind of nonviolence.

Problematizing Ecclesial Nonviolence

I have also come to the conviction that ecclesial nonviolence is incomplete at best and a bit problematic at worst.

Two major events have led me to this conviction.

The first happened in the middle of my time at Baylor. Ever since becoming a self-proclaimed Yoderian, I had heard vague allusions to Yoder’s idiosyncratic views on sexuality within the church. As with many white male Yoder scholars in the early 2000s, I had brushed this aside as either a strange personality quirk or some kind of theological exploration that was unrelated to his pacifism.

Then in 2013, a number of women, mostly from the Mennonite Church, publicly and forcefully named Yoder’s actions for what they were: a form of violence. The fact that arguably the most influential voice for Christian pacifism in the 20th century—and certainly the most influential theologian for me—was himself a perpetrator of sexualized violence was disorienting for me, to say the least.

The second event that complicated my views of ecclesial nonviolence was that on January 1, 2017—with my newly minted theology PhD in hand—I began pastoring a small evangelical congregation in a low-income neighborhood in South Bend.

Nineteen days later, Donald Trump was inaugurated as the 45th president of the United States.

I learned through the crucible of leading a congregation through the tumultuous four years of Trump’s presidency—the last of which included a pandemic—that declaring the church as the alternative to the violence of empire required a number of caveats.

Theological aphorisms I had absorbed, like “Let the church be the church so the world can be the world,” started to ring hallow when the world was killing my neighbors, often with the vocal support of the church writ large.

The denomination that we were members of at the time started careening headlong into Christian nationalism. Although I had long been convinced to stay true to the church of my baptism, as a pastor I became even more convinced that faithfulness to the gospel required realigning our church’s denominational ties. This ultimately landed us in the Mennonite Church, the place from which our former denomination had splintered off over a century prior.

Our church’s mission statement is to “seek the peace [or shalom] of our neighborhood by sharing God’s love with our neighbors.” And our vision is “to become a church that follows Jesus, the prince of peace, and embodies God’s peaceable kingdom in the Keller Park neighborhood, the city of South Bend, and beyond.”

I learned that embodying this mission and vision requires more than rejection of war. It requires speaking up and acting on behalf of those in our community who are being deprived of shalom—whether due to socio-economic status, citizenship status, racial or ethnic identity, gender, sexuality, disability, or some combination thereof.

Finding Nonviolent Alternatives

Through this all, I sought to stay true to my pacifist convictions. In addition to pastoring, I had begun working at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, where I teach the course Christian Attitudes toward War, Peace, and Revolution. This course originally had been designed and was then taught for decades at AMBS by John Howard Yoder. Due to Yoder’s troubling legacy at the seminary, I set out to redesign the course in such a way that none of Yoder’s writings would be required reading. While this was not without its challenges—as Yoder had literally written the book Christian Attitudes toward War, Peace and Revolution!—I found it refreshing and inspiring.

I realized that in my laser-sharp focus on Yoderian nonviolence, I had missed out on a great cloud of witnesses to Christian nonviolence in the 20th and early-21st centuries. These witnesses spoke in different registers and from different contexts from what I was used to. They differed in their understandings of what constitutes violence and how best to respond to it. They differed in the biblical and theological underpinnings for their understandings of nonviolence. But they all shared a desire to faithfully live out the gospel of peace in their respective contexts.

And so, with my Baylor colleague Myles Werntz, I wrote A Field Guide to Christian Nonviolence to make sense of this diversity of Christian witnesses to nonviolence.

As we state in the introduction, our argument is that

Christian nonviolence, at its best, does not promise to end all wars or permanently settle all disputes. Rather, Christian nonviolence is an exercise of Christian wisdom, guided by the Spirit, who transforms our minds so that we “may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom. 12:2).

The question for us to discern as we conclude this EP gathering, then, is this: How is the Spirit guiding us to embody the gospel of peace in our contexts today?

I understand the concern that EP seems to have shifted over the years in its articulation and expression of nonviolence and shalom. But I would like to suggest that this is at least in part because our context has shifted.

As a number of long-time EP participants have reflected, EP’s expression of nonviolence in the early years was in large part a response to 9/11—that is, to American empire and U.S. wars abroad. It is fairly easy to remain non-partisan when Republicans and Democrats alike dismiss you as the pacifist voice crying out in the wilderness.

But in subsequent years, American empire has come home to roost in the form of white Christian nationalism, which found its biggest promoter in a sexually violent reality TV personality who rode his way to the White House on 81% of the evangelical Christian vote.

According to Indianapolis-based sociologist Andrew Whitehead in his new book American Idolatry, “Close to two-thirds of white American Christians are at least favorable toward Christian nationalism, and that number increases to over 75 percent if we look solely at white evangelicals.”

This is a problem not only for the United States but also—and perhaps especially—for the church. January 6, 2021, has become the new 9/11 for our current generation.

Trying to embody nonviolence in this new reality might not make you a Democrat, but it should at least make you not a Republican. And while we may lament a two-party system that provides no obvious third way for radical Christian politics to gain traction, I believe that Christian faithfulness requires us to discern the signs of the times instead of waxing nostalgic for the good old days when everybody was equally against us.

A Great Cloud of Witnesses

In our remaining time, I want to introduce witnesses to the gospel of peace that may have gotten overshadowed at EP by Yoder’s influence but who may provide us resources for discerning what nonviolent Christian faithfulness might look like for us today.

In our book, we organize these witnesses under 8 different headers, which represent 8 different approaches to Christian nonviolence:

- nonviolence of Christian discipleship,

- nonviolence as Christian virtue,

- nonviolence of Christian mysticism, A

- apocalyptic nonviolence,

- realist nonviolence,

- nonviolence as political practice,

- liberationist nonviolence, and

- Christian antiviolence.

I trust that many of us are familiar with Reinhold Niebuhr’s distinction between two forms of pacifism that he witnessed in his day.

The first was a more inward-focused, quietist, absolutist, communalist pacifism that focuses on fidelity to Jesus’s teachings on nonresistance and in so doing offers a witness to the world of another kingdom without trying to change the world.

And the second was a more outward-focused, activist, political pacifism that takes Jesus’s teachings less literally and focuses instead on the effectiveness of nonviolence, using nonviolence as a tool for social change and political transformation in the world.

Niebuhr’s distinction has persisted in the popular imagination, as the first, communal kind of nonviolence has come to be associated with names like Yoder and Hauerwas—and, by extensions, the Ekklesia Project—and the second, political kind of nonviolence has come to be associated with Martin Luther King Jr. and nonviolent movements for civil rights.

Perhaps we might think of this distinction in terms of whether one prefers to render dikaiosune in the Beatitudes as “righteousness” or as “justice,” as in, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for dikaiosune, for they shall be filled.”

I structure my presentation of the 8 streams with this distinction in mind, beginning with 4 streams more often associated with the first type and ending with 4 streams more often associate with the second type.

After presenting each of these two groups, we’ll take some time in groups to discuss these questions:

- How does each stream of Christian nonviolence resonate with my own understanding of Christian nonviolence—or that of EP more generally?

- What about each stream do I find challenging or even troubling?

- What might it look like to practice each approach in my church context?

- What might it look like for EP to embody this approach to nonviolence going forward?

In doing so, I think we’ll find Niebuhr’s distinction to be a bit simplistic, as each stream has its own unique theo-logic.

[For a discussion of these 8 streams, see our book or watch the video when it goes live on EP’s YouTube page!]

Conclusion

Christian nonviolence is not as a settled position but is rather as a form of Spirit-led moral discernment about that which is “good and acceptable and perfect” in God’s world (Rom. 12:2). The 8 streams reach the conclusions they do because of different underlying theo-logics that animate them.

For Christian nonviolence to live into the future, it not only must address itself to the old ways of violence but must also include a vision for addressing the proliferation of new forms of violence. As we move further into the twenty-first century, we can continue to learn from the great cloud of witnesses to Christian nonviolence in its many forms from the 20th and early-21st centuries that we have surveyed.

What is ultimately needed to face new challenges will not be a single, unified form of Christian nonviolence but a proliferation of new forms, each drawing wisdom from the past while looking ahead to ever-evolving challenges. This will mean the willingness of proponents of each stream to acknowledge that those from the other streams are likewise anticipating the peace of God in their practice and witness and to creatively and patiently live in witness to the prince of peace who heals the world of all the various forms of violence in it.

I want to thank EP for its vital role in this work in the decades since 9/11 and to invite you to continue this work in new ways as together we face the challenges that lie ahead. May the peace of Christ be with you as you do. Thank you.