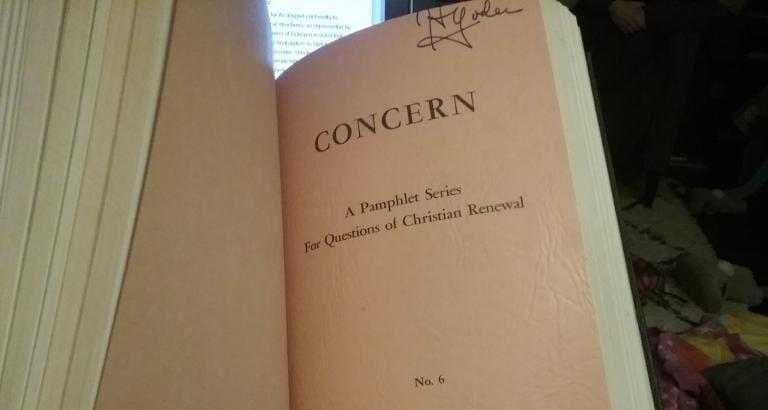

One cool thing about working at AMBS is that there’s a table of free books in the lounge—books that have been remaindered by the library or donated by retired faculty or alumni. And sometimes those books include John Howard Yoder’s personal bound copy of the first eight issues of the Concern pamphlet series.*

As GAMEO describes,

Concern is the name given to a series of pamphlets initiated by a group of young American Mennonite graduate students, relief workers, and missionaries who met in Amsterdam in 1952 to address issues confronting the Mennonite church in Europe. Although the “Concern Group” preferred not to be known as an organization or even as a fellowship with defined membership, the initiating participants consisted of Irvin Horst, David Shank, Orley Swartzendruber, John W. Miller, Paul Peachey, Calvin Redekop, and John Howard Yoder. They felt led to further discussions focusing upon the condition of the American Mennonite church in relation to its founding principles as represented by the “Anabaptist Vision.”

As I described in a previous post, Harold Bender‘s “Anabaptist Vision” can be understood as the instigator of neo-Anabaptism, and the Concern group—especially Yoder—as its original propagators.

So far as I can find, the word “neo-Anabaptist” was coined by the Concern group as a self-designation. Around the time of the Amsterdam conference, Yoder wrote an essay with the impressive title, “Reflections on the Irrelevance of Certain Slogans to the Historical Movements They Represent: Or, the Cooking of the Anabaptist Goose; Or, Ye Garnish the Sepulchres of the Righteous” (commonly referred to as simply “The Cooking of the Anabaptist Goose.” There Yoder writes,

A major refutation of the rationalist view of man may be seen in the evident disparity between what men do and what they sincerely think, and say, they are doing. A curious example of this phenomenon may be seen in a series of events which transpired during the second quarter of the twentieth century, and which may be called the neoanabaptist movement. The first clear recognition of the nature of this movement came in 1952 at Amsterdam at a graduate students’ seminary (the neoanabaptist equivalent of a Martyrs’ Synod).

Not everyone at the Amsterdam meeting was enthusiastic about the neo-Anabaptist movement. In an epistolary exchange published in the fourth volume of Concern, Irvin B. Horst writes,

I have a sheaf of letters which arrived following our Amsterdam conference which perpetuate some of our mutual concerns and on which I wish to offer a few comments. . . . It is clear that Amsterdam was not just another conference—at least not for me. Certain things have fastened on to my convictions: (1) that the bright child of neo-anabaptism is not adequate—is impotent to make new Anabaptists; but that we need to be thankful to those who have husbanded and nurtured the child and not throw the baby out with the bath water. (2) Neo-anabaptism is chiefly academic, an interesting subject to build libraries, journals, lectures around—but not to adopt personally in our daily lives.

Years later in volume 12, one of the original Concern members, John W. Miller, quotes Horst’s words against himself in the essay “The Renewal of the Church“:

There are scholars and teachers in the church who have made a kind of profession out of writing and speaking about the Anabaptist Vision. They are respected members, not only of a particular denominational party, but of the ecumenical community.

However, it is questionable whether they would have joined the Anabaptists in the sixteenth century, and as of now on their own admission, and for reasons they consider justifiable, do not practice what they advocate. A good friend of mine was critical along similar lines some years ago. In letters which were subsequently published in the fourth issue of Concern he wrote: “The bright child of neo-Anabaptism is not adequate—is impotent to make new Anabaptists . . . . Neo-Anabaptism is chiefly academic, an interesting subject to build libraries, journals, lectures around-but not to adopt personally in our daily lives.” Ironically, this friend is now in process of building up still another library devoted to the memory of his persecuted forebears. Our Mennonite schools, it seems, do not feel complete without such a collection of Anabaptistica, or at least some sign of loyalty to the Anabaptists of old.

For Miller, devotion to “the memory of . . . persecuted forebears” and collections of “Anabaptistica” at Mennonite schools are signs of hypocrisy for those who claim to be devoted to the radical Jesus movement. The renewal of the church, then, comes not through institutions but through complete devotion, in thought and in action, to the vision of the 16th-century Anabaptists, which ultimately reflects the vision of Jesus himself.

As Yoder writes in the programmatic essay “What Are Our Concerns?” (vol. 4),

There is a definite relation between the [Concern] group’s convictions and reactions and the new understanding of the Anabaptist movement [of Bender]. The Anabaptist fad in American Mennonite circles is already a generation old, but this group has gone beyond studying the Anabaptists and admiring their depth of conviction and reached the conclusion that on many points they were right and should be followed. The claim is not that the Anabaptist movement was infallible but that on a surprising number of points they were led to right answers which retain an exemplary value for our time.

Thus, while for Yoder the Concern group “considers itself committed to the Mennonite fellowship in which its members grew up,” he adds a caveat: “insofar as that fellowship is willing to be renewed by rededication to its own heritage and to Biblical faith.” However, in a later (1969) essay, “Anabaptist Vision and Mennonite Reality,” Yoder uses the Anabaptist vision “as a criterion as we look at the recent history and present reality” and, not surprisingly, finds “Mennonite reality” wanting.

After the first generation of neo-Anabaptists who grew up in the Mennonite church, then, the following generations of neo-Anabaptists who didn’t grow up in the Mennonite church felt no reason to join it in order to live out the Anabaptist vision in their time. So today, as I described in my previous post, neo-Anabaptism is primarily a movement outside of traditional Anabaptist-Mennonite groups and structures. And the Concern movement, for better or worse, is largely responsible for this phenomenon.

*For those who don’t have access to hard copies of the Concern pamphlet series, the essays are available digitally through the AMBS library. The first four volumes of the series have also been published together by Cascade as The Roots of Concern: Writings on Anabaptist Renewal 1952–57, edited by Virgil Vogt.