Melissa Florer-Bixler’s book Fire by Night: Finding God in the Page of the Old Testament is out today from Herald Press! As I mentioned in my introductory post on the book, instead of writing a traditional review, I plan to blog through the book chapter-by-chapter. Pick up a copy ASAP so you can join the discussion!

Today we look at chapter 1, “God of Reckoning.” In this chapter, Rev. Florer-Bixler describes her practice of retreating to St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota to join Benedictine monks for prayer. Instead of using the Bible as quick-and-easy answer guide, the monks slowly recite passages of Scripture during their prayer time, including long pauses for silent reflection. Reading Scripture this way causes you to hear it differently, suggests Florer-Bixler.

And so she invites readers of Fire by Night into a slow meditation on the words of the Old Testament (as Christians refer to the Hebrew Scriptures). While many Christians find the God of the Old Testament unsettling and even off-putting, Florer-Bixler finds through her slow read of the Old Testament that it “offers a different picture of God. The arc of God’s story with the people of Israel is consistent—humans mess up and God is relentless in forgiveness and grace. Over and over Israel makes promises they cannot keep. Over and over again God is faithful. This narrative unfolds within the gritty details of vengeful, murderous, and at times disarmingly beautiful lives” (25).

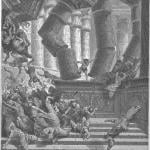

Indeed, the common Old Testament/New Testament divide fails to recognize that passages from the New Testament also can be and have been used to justify atrocities throughout the history of the church. Florer-Bixler mentions a passage from Titus that the monks recited, which was used to justify the North American slave trade. In this case, ironically, slave holders taught slaves passages from the New Testament to keep them in submission but tried to keep from them narratives from the Old Testament, such as the exodus, that speak of God’s desire for the liberation of enslaved people.

For Florer-Bixler, Christian must reckon with the way we have used Scripture (both Old and New Testaments) to justify such atrocities as slavery. She writes, “I stand before these words, receive them back, and dare not look away. This reading binds me to a past that is never past. With the monks, standing before this reading from Titus, I’ve come to see that the Bible is a reckoning, where we come face to face with what we have done with the Bible or what the Bible has done to us” (27).

And then comes the kicker, which I read as the thesis of this chapter:

“We cannot escape the interpretive communities we form, and these communities matter for how we will read the Bible today. Whenever we read the Bible, we participate in a history. In that history are those who have turned the good news into both joy and terror” (27).

Reading the Bible in community means recognizing that not every text is intended for comfortable white Americans. That isn’t to say that these texts can’t speak to them (me); it just means they aren’t for them. Instead, Florer-Bixler writes, many of the Scriptures “are words for the enslaved, words of protest, words of judgment that well up from lives terrorized by sexualized violence, torture, kidnapping, and slavery. They are words that express God’s fierce solidarity with the marginalized” (29).

If Florer-Bixler’s understanding is right, then the implication is that we probably can’t rightly interpret the Old Testament (or Scripture in general) if we aren’t reading it in community with the marginalized. She mentions the Anabaptist practice of zeugnis, or “testimony,” in which congregants are given space after the sermon to respond to what was spoken in order to communally discern what God is speaking (36). But if everyone in the congregation is from a homogenous racial and socioeconomic background, we are unlikely to be able to communally reckon with the God of Scripture. There is a tight hermeneutical spiral at work: the God of Scripture calls us into solidarity with the marginalized, and only in such diverse fellowship can we hear God’s calling through Scripture.

This offers a double-challenge to those like me who grew up in middle-class, white evangelical contexts.

First, while there is certainly a time and place for the kind of private, personal, devotional reading of Scripture that is encouraged within evangelicalism, Florer-Bixler emphasizes the necessity of reading Scripture in community. And sometimes this communal interpretation will challenge and even correct one’s personal understanding of the text.

Second, while evangelicalism tends to emphasize the perspicuity of Scripture—the idea that Scripture is sufficiently clear to be understood by anyone with whom the Spirit dwells—Florer-Bixler’s reading suggests that, at least in some instances, the Spirit can only be heard within diverse community.

While this suggestion is provocative, it seems to be supported within Scripture itself. In the Jerusalem Council described in Acts 15, it wasn’t until the voices of those who had witnessed the Spirit’s work among Gentiles were heard that the early Christian community could reckon not only with what God was doing in history but also with how to understand the prophets of old testifying to this work. As James stated in that meeting: “Peter has told you about the time God first visited the Gentiles to take from them a people for himself. And this conversion of Gentiles is exactly what the prophets predicted” (Acts 15:14–15). Here’s the question: Would James have known that that’s exactly what the prophets predicted if he hadn’t first heard Peter’s testimony?

These are some thoughts that arose as I read chapter 1, but I’m just one reader. For those of you who are reading along, what stood out to you? Let me know in the comments. For the rest of you, what are you waiting for? Go buy Fire by Night and join the discussion!