Today’s post is written by Andrew Steven.

If you would have asked any doctor before 2007 what your appendix does, they would respond with, nothing. It serves no purpose. A remnant of the past. Perhaps an evolutionary glitch. That’s one of the reasons we are quick to remove them when they become infected. But in 2007, a team of scientists from Duke University discovered a fundamentally new idea about how the appendix works. Our appendices, as it turns out, are basically store houses for beneficial bacteria that help us “reboot” when other good bacteria dies off.

Before 2007, most doctors would swear with absolute certainty that your appendix is useless. Today, with that same certainty, they’ll tell you how beneficial it is.

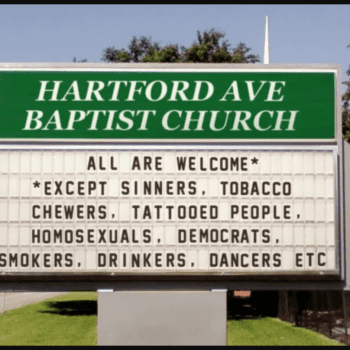

Growing up in a faith community can feel similar. Religion can become a place where honest curiosity and confusion are not permitted. I’ve heard many stories of people experiencing real doubt and questions, only to be told by their pastors to stop thinking so much, to fall into place, and to keep quiet. Perhaps their pastor’s intentions were in the right place, but those actions have consequences.

My parents raised me as a Christian and took me to church regularly. It was not only an integral part of my weekly schedule, it was a major part of my identity. And like many who were raised similar, I understood the Bible to be a literal, infallible, perfect word of God. Because of this, I still remember when someone told me to find a specific passage in the Bible. They asked me to turn to Matthew 17:21. It wasn’t there. It should have been. Matthew 17:20 and 17:22 were there. Only the footnotes offered a poor explanation, Some manuscripts include… and then the verse. Even today, searching for “Matthew 17:21” on the world’s most popular online Bible, returns with, “We’re sorry, the page you’re looking for can’t be found.” I then learned there were even more passages omitted from the Bible.

Discovering that my Bible seemed to be edited, censored, and fixed, changed the way I read it. I felt like a Duke scientist, suddenly realizing that much of what we thought to be true was actually not. I felt confused. I felt tricked. I felt lied to. And because much of my identity was wrapped up in being a “christian,” I began to question who I was.

There are many reasons scholars and pastors give for why certain verses are omitted from the Bible, most of which make a lot of sense. I still love the Bible and believe it to be a inerrant, integral part of my faith. But I also believe that doubt plays an important part as well. Faith and doubt are not two sides of the same scale. More doubt does not equal less faith. Or as Rob Bell says in his new book:

“For many people in our world, the opposite of faith is doubt. The goal, then, within this understanding, is to eliminate doubt. But faith and doubt aren’t opposites. Doubt is often a sign that your faith has a pulse, that it’s alive and well and exploring and searching. Faith and doubt aren’t opposites, they are, it turns out, excellent dance partners.”

As a child, when I had doubt, I was taught to hide it. To forget it. To try and will it away. It’s this dangerous practice that infects religion and promotes quitting Christianity.

When people meet Jesus, their lives change. When people meet religion, their routines change. Most of us change our routines in hope that our lives will also change and we’re surprised when we find ourselves back to where we were before, with little difference in our lives, having replaced relationship with legislation, and conversation with silence.

The debate is holy.

The struggle is divine.

Faith is a conversation.

Following Jesus is a dance.