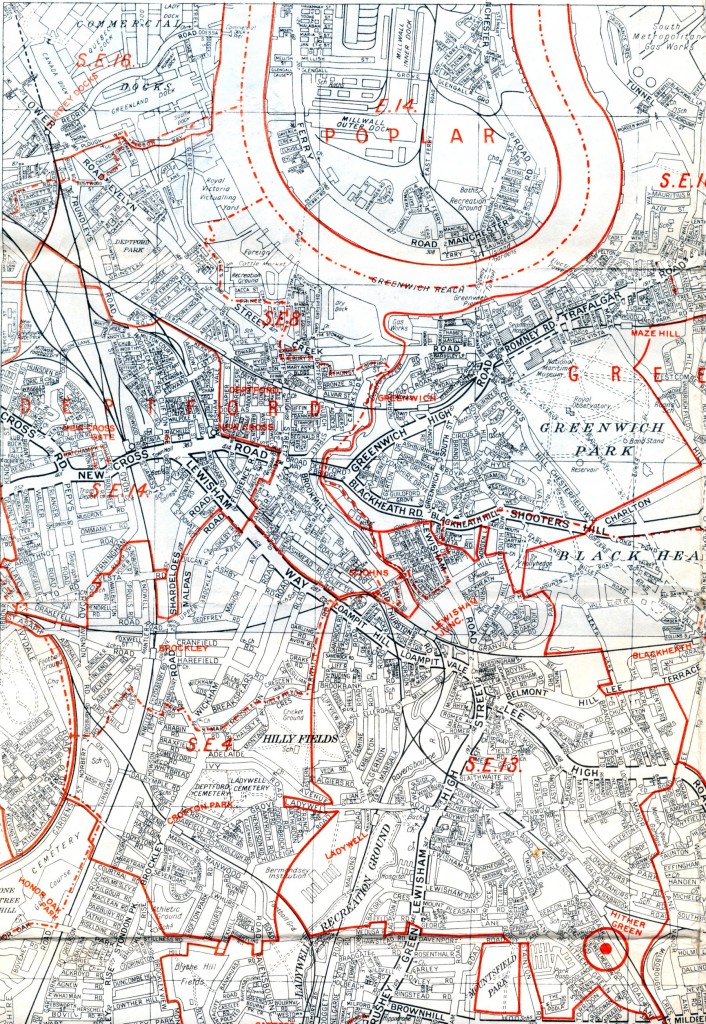

I was born in South London (pronounced “Saaarf Laarndun”), in the area of Lewisham — you can’t get much more urban than that — and I was raised in England’s second largest city, Birmingham. And yet, since adolescence, I’ve felt ill at ease with city life.

High res version available from Probert Encyclopaedia

Disaffected living

My (limited) studies of French philosophy helped me to see I wasn’t alone in this experience. Durkheim had a word for my situation: l’anomie – the feeling that I lacked community. Sartre had a word for it, too: la nausée – the sense of despair I felt at the world’s indifference to my existence.

I got the first intimations that a different life was possible at Glastonbury Festival in 1993. I was volunteering with West Midlands CND, holding fort at the left luggage tents around various of the fields along with my fellow activists. As a volunteer, I was on site for nearly an entire week. I was in a place where I could connect directly with the shape of the land, the state of the ground, the way earth became trees became sky. There was nothing but earth and grass on the ground, nothing taller than a sound stage on the horizon.

Not only that, but the people…

Whether it was being released from the nine to five into a long weekend of free-wheeling festi living, or getting to hang out with their friends and enjoy their favourite music live, or the availability of the healing field, people were for the most part what I had always dreamed people could be — what we should be: loving, generous, happy.

This was my first taste of feeling part of a place, being in relationship to a place — and a community — rather than being a disconnected dot, scurrying about a Tarmacked surface, or a small cog in the machine-like institution of school or college.

It was an experience which shaped my ideas about how I wanted to live.

Looking for a different life

At first, my focus was on finding a humane, human community, based on reciprocity, mutuality and generosity. I found it for a while in workers’ and housing co-operatives, but I had yet to develop the perspective and the personal resilience to deal with the conflicts of personality, perspective and priorities which inevitably arise when working and living in a group — even a group whose members share ideals.

And we were still part of the atomised city, still surrounded by l’anomie and la nausée.

I gave myself a break from idealism, and simply followed life where it led me for a few years. Where it led me in the year 2000 was to a wee cottage in an isolated rural parish in southern Scotland, along with my partner and our dogs.

This was where that different life began to emerge: not from the people I surrounded myself with – there were precious few of those around! – but from the relationship I developed with this new land.

Learning the all-species, more-than-human tribe

I spent a great deal of time outdoors in that first year in our new home, just noticing. My tools were a curious mind, open senses, and waterproofs.

I came to know what rain looked like from a distance, and how to tell if it was coming our way. I learned the scent of clover and moist earth in sunshine. I thrilled at the sight of herons almost within arm’s reach. I began to recognise wild plant and animal neighbours which were new to me: vetch, water avens, blueberry, St. John’s wort; buzzard, sparrowhawk, hare, red squirrel.

And in coming to know the land and all of its living peoples, I also gradually came to know the spirit species which populated it, too: the devas, the sidhe, the very substantial elements. Above all else, I came to recognise the presence and actions of the Cailleach, of Angus, and of Bride, the legendary shapers of the land of Scotland.

Finding community, being in relationship, becoming myself

Through this process of finding community with my fellow beings, I have learned not only how to listen to and hear the non-human inhabitants of this land, but also how better to relate to the humans in my life. This is because being in relationship with the more-than-human has enabled me to land ever more fully into myself.

Being in relationship, I know that I am not alone, that I have a place, that I am at home, right here, right now.

This takes the anxiety and the pressure out of every interaction I have with other humans, whether they are family, friends, neighbours, acquaintances or distant bureaucrats. Through knowing myself connected to the land and its all-species, more-than-human tribe, I also know myself connected to my human kin.

L’anomie and la nausée are gone, and I’m hopeful I now have the skills and tools to ensure that, even if I find myself living in a city again, they’ll never return.

Do you find city living a challenge, or is country living your idea of hell? How does your religion and your spiritual practice help you to find a deeper connection, right where you are?