I went to see General Orders No. 9 at the Georgia State University campus theater. It is not a film for the impatient. It has no plot; what narrative there is meanders and recurses. The narrator doesn’t explain anything so much as pose more questions. “Documentary” is as good a label as any, and the film includes fascinating footage of old maps of Georgia. The title is a reference to the last orders given by General Robert E. Lee to the Army of Northern Virginia after his surrender at Appomattox…but the film is not about the Civil War. There is a point where the narrator says, “There was a war here, a hundred years before the present generation was born. There was a war here,” but I don’t think he’s talking about the Civil War then, either, not really. It’s a metaphor, y’all.

Neither the director nor any of the other contributors to the film are Pagan, to my knowledge. There are some Biblical references, as well there might be in a film set in a place so steeped in Christian religion as the South. Despite this, I think it might be one of the most Pagan movies I’ve ever seen. At the very least, it’s resolutely “pagan” in the Latin sense: paganus, rural. One of the major concerns of the film is the tension between community on a human scale and the inhuman detachment of “the city” which is both a specific city (Atlanta), all cities, and a mode of life. General Orders No. 9 reminds us insistently that the landscape is alive and present and multifaceted and real, and that a humane and comprehensible culture is grounded in that realness, but many of the structures and presumptions of our society conspire to strip us of it: “The Interstate does not serve, it possesses…it has the power to make the landscape disappear from our attention.” There are, in that living landscape continually disappearing from our sight, snakes and turtles, forests, rivers, dogwood blossoms, red dirt and pine trees, all continuing lives unknown to us whether we pay attention or not. That we don’t is our loss, and a devastating one: “I came here and my heart was made desolate….The city is not a place, it is a thing. It has none of the marks of a place, and all those of a machine.” The implication being that a real place is alive, not just full of life but actually living. This is the sort of thing I mean when I say the film is very Pagan; it’s simultaneously very, very Southern. It’s not quite a coincidence that the name of No Unsacred Place comes from a Wendell Berry quote. Scratch a typical Southerner, whatever his or her stated religious affiliation, and you’ll find a pantheist. We’re all in love with our genius locii.

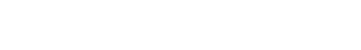

Then there are our ancestors, who are neither forgotten nor remote: “….you will see them. Ask them to look over us. The dead pray for the living, just as the living pray for the dead.” The film spends a lot of time on cedar trees and cemeteries and empty rooms. The past is numinous and tangible in the film in exactly the same way as in the Georgia landscape: in stone monuments and rows of headstones, in old buildings, in the shape of things, in its influential and weighty absence. We see artifacts, starting with Cherokee pottery shards at the very beginning of the film, held by human hands; by this we are reminded that the past holds not just events or abstractions, but people. The past is important in the world of the film not as the progress of empires, but because it is part of the landscape, and because it is important to individual human beings. One gets the impression that the narrator would just as soon all empires ground down to dust, if one could accomplish that while leaving the small communities standing.

Not that the film offers any such simple solutions, even impractical ones. It warns: “You do not witness the ruin. You are the ruin. You are to be witnessed.” I was conscious of the irony of hearing this, and the film’s passionate if beautifully stated distaste for cities, while sitting in the middle of the most concrete-bound and urban university campus in the region (and my alma mater). The film is likewise aware of its own ironies, and contradicts itself with Whitman-esque freedom. It engages with the living landscape in a complex, sometimes uneasy way, and invites the rest of us to do the same. “The center of the state is the county; the center of the county is the town; the center of the town is the courthouse; the center of it all is the weathervane.” There are scenes in the film depicting both agriculture and tornadoes. All attempts at comprehensible human existence must be grounded in and centered on nature, which can be simultaneously nurturing, unpredictable, and dangerous. The narrator calls this “the only true thing.”

General Orders No. 9 is showing at selected theaters around the country; more information can be found at the website.