Our modern difficulty with the idea that we are created by God may well spring, not from any lopsided view of God, but from a lopsided view of creation. These are corporate days, and creation brings to mind the world of business, that is, creation which serves a useful purpose for its creator, whether by the accumulation of profit or the convenience that it brings.

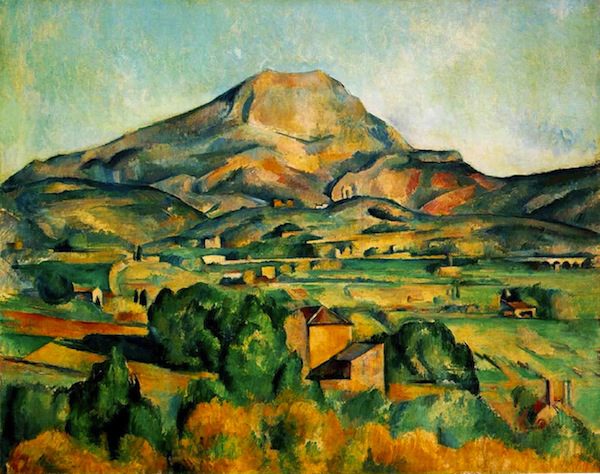

But God is not a capitalist. He does not seek to gain by creating us. God is an artist, and art has the remarkable quality of uselessness, transcending the category of use by being good in itself. The purpose of art is simply to be, clearly and in wholeness. The mind stutters at the question “What is the use of a Cezanne?” because the question seeks to wedge that which exists for its own sake into the category of economy, the category of objects which exist to serve some useful purpose.

Dawkins-type atheists — may they be blessed, kept, and their Twitter followers multiplied — often bring up the apparent egoism of God as a super-effective strike against his non-existent character. The late great Hitchens harped on this point, drawing a confident connection between God and Kim Jong Il: Is he really so needy for attention, so desperate for affirmation that he had to create people to praise him? But this is a fundamental misunderstanding of praise, one that arises from a conception of a capitalist-God, that is, a creator who seeks to get from his creation.

Praise is not an addition to God, as if every time I mutter through the Divine Praises the Lord of Heaven and Earth gains 20 self-esteem points and doesn’t feel like he has to post on Facebook that evening to make sure people still like him. Praise is honesty. God gets nothing from praise, rather, praise admits what is already true of him and his relation to us. It is true that we are contingent beings entirely dependent on Love for our existence, and to fall on our knees and express this fact is not to compliment God — it is to be honest. It is true that God is Beauty, and to sing this out in ecstasy is not our effort to bolster God’s ego, it is our effort to live in truth, to express authentically our relation to Eternity. It is precisely because praise has nothing to do with compliment that the greatest record of human praise in existence — the Book of Psalms — spits piss and vinegar at God in praise:

I have been mortally afflicted since youth;

I have borne your terrors and I am made numb.

Your wrath has swept over me;

your terrors have destroyed me.

All day they surge round like a flood;

from every side they encircle me.

Because of you friend and neighbor shun me;

my only friend is darkness. (Psalm 88)

If you cannot understand that these words praise God, you cannot understand religion, for praise bears witness to the reality of our relation to God, and is thus, properly understood, stuffed with as much obscurity, uncertainty, anger, and frustration as with peace. The spiritual problem of modern, evangelical atheism is that it refuses to comprehend the fact that the Christian, insofar as he is a Christian, has his eyeballs pressed against his God in the same way one touches noses with a lion. We behold the unbeholdable with a joy that does not exclude terror. Until the new atheist discovers that there is more anger against God, more doubt in his presence, more uncertainty in his nature, more sickening over his absence, in short, until he discovers — perhaps through Nietzsche — that there is more atheism in the Judeo-Christian tradition than there is in his atheism, the religious man will remain an incomprehensible absurdity and his psalms ridiculous.

But this brings us back to our conception of God as artist. If we were made to praise God, and praise is existential honesty — that prayerful witness by which we declare the truth about God, ourselves, and the convergence of the twain — then saying “we were made to praise God” is synonymous with saying “we were made to be.” To be made to praise is to be made to show the truth about yourself in all clarity — to be who you are in fullness.

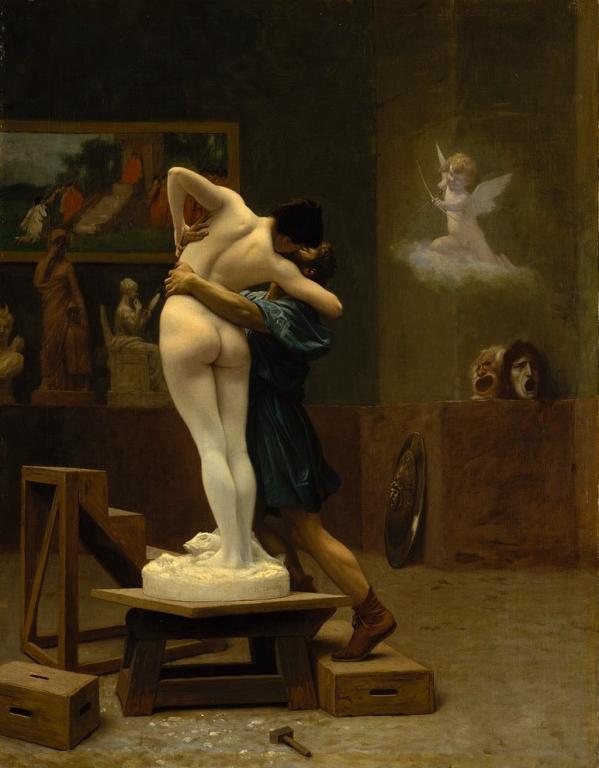

Art for art’s sake, says Oscar Wilde. Art with no higher purpose than being itself and revealing itself in clarity, splendor, wholeness and truth. The person for his own sake, we say in our modern, Christian-based affirmation of the universal dignity of every man, but do we recognize the connection? Man exists for his own sake, and as such may be understood as a work of art, a poem in love with its poet, a symphony aware of itself and overflowing with gratitude towards its composer for the fact of being, and being beautiful. Here many myths speak of an already sensed connection between the person and the work of art. We are that statue loved into life, that marvelous piece of clay-work whose lungs hum with the breath of our creator, made for our own sake, and more — made to know it.