There is a reason to draw a strong analogy between the human person and the work of art. This connection first tickled my brainstem when I saw that both exist for their own sake, but the fact that art transcends the category of use is just one of its aspects, an aspect which, taken on its own, is an insufficient explanation of art itself. There is another way in which the work of art and the human person are similar — in freedom. To explain this, I need to describe the act of writing poetry.

What I risk here is subjectivism, but I simply cannot start making statements about “the poet in general” without making massive, sweeping generalizations which are the downfall of 98% of my essays. My request to the reader is that you read my first-person experience of the act of artistic creation and, for your own part, find the degree to which this first-person experience agrees with your own experience — only then will we make extrapolations to the nature of things.

When I write a poem, I do not copy the idea of the poem from my mind to the paper. The poem does not have a mental existence that I actualize through clacking power of my typewriter. I write poems in a cloud of uncertainty, apart from any fixed vision of the outcome of my efforts. In simple English, I do not know what the poem will be until it is done.

This is weirder than people give it credit for. When we want to draw a triangle we do not draw a square, tilt our head, squint, say, “no that’s not quite it yet,” and sharpen our pencil for a second draft. Yet this is precisely how we write poetry. I experience my act of creation as being guided by the work itself. I look at my first draft and says “no, that’s not quite it,” even though I cannot articulate what “it” should be, for if I could, I would have no need of drafting, I would just write down precisely what I knew “it” to be. Thus, in my experience of poetic creation, the poem is on one level entirely contingent upon the poet — who creates it — and on another level free — for the poem itself will tell me what it wants to be, will determine its own completeness.

The poem presents itself as a paradox: I do not know what it is, except in the act of writing it down. Discovery and creation are simultaneous — I discover what the poem is in the act of creating it. In all other forms of production, I am guided by some fixed standard. When I am making a car, I know what I want the car to be. When I am tilling a field, I operate according to a preconceived understanding of what the field should be. These products are determined. When I am writing a poem, I may have some inkling of what I want it to be, but this inkling may be incomplete, or even false — as when I realize that I wasn’t writing about the sea at all, it was about her, and so I erase the cliches and start again. This “inkling” is far from a determining idea of what the poem will be. It is experienced — in the words of the 20th century French aesthetician, Mikel Dufrenne — as a “demand.” I don’t mentally experience the work of art in its fullness — whether the poem, painting, song, etc. — rather, I experience the demand for that work of art to be actualized, even if I have no or little idea of what that work of art will ultimately become. This demand may be no more than a feeling of creativity, the strange pull of a necessity to write, to paint, to compose, or the singular line that pops into the head and demands to be fully actualized into the whole of which it may only be a part, or the whole which it only evokes (who knows which — I’ll find out soon enough).

some inkling of what I want it to be, but this inkling may be incomplete, or even false — as when I realize that I wasn’t writing about the sea at all, it was about her, and so I erase the cliches and start again. This “inkling” is far from a determining idea of what the poem will be. It is experienced — in the words of the 20th century French aesthetician, Mikel Dufrenne — as a “demand.” I don’t mentally experience the work of art in its fullness — whether the poem, painting, song, etc. — rather, I experience the demand for that work of art to be actualized, even if I have no or little idea of what that work of art will ultimately become. This demand may be no more than a feeling of creativity, the strange pull of a necessity to write, to paint, to compose, or the singular line that pops into the head and demands to be fully actualized into the whole of which it may only be a part, or the whole which it only evokes (who knows which — I’ll find out soon enough).

Again, the poem exists as a synthesis of contingency and freedom. This is true even after the act of poetic creation, in which the poem may “say” something the poet did not intend to its readers. True, Fleet Floxes wrote the words…

In the doorway holding every letter that I wrote

In the driveway pulling away putting on your coat

In the ocean washing off my name from your throat

In the morning, in the morning

…and these words are contingent upon their act of creation, but the meaning of the words, that is, the poem itself still exists in a space of freedom where it may “speak differently” to different people.

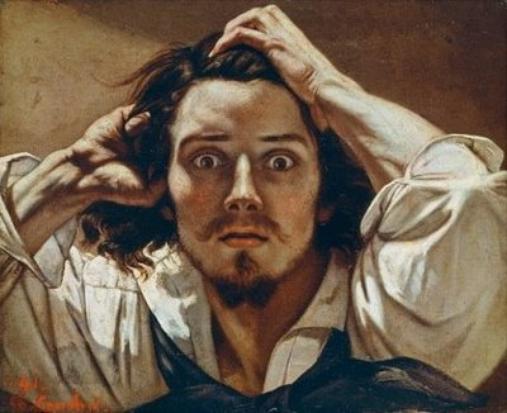

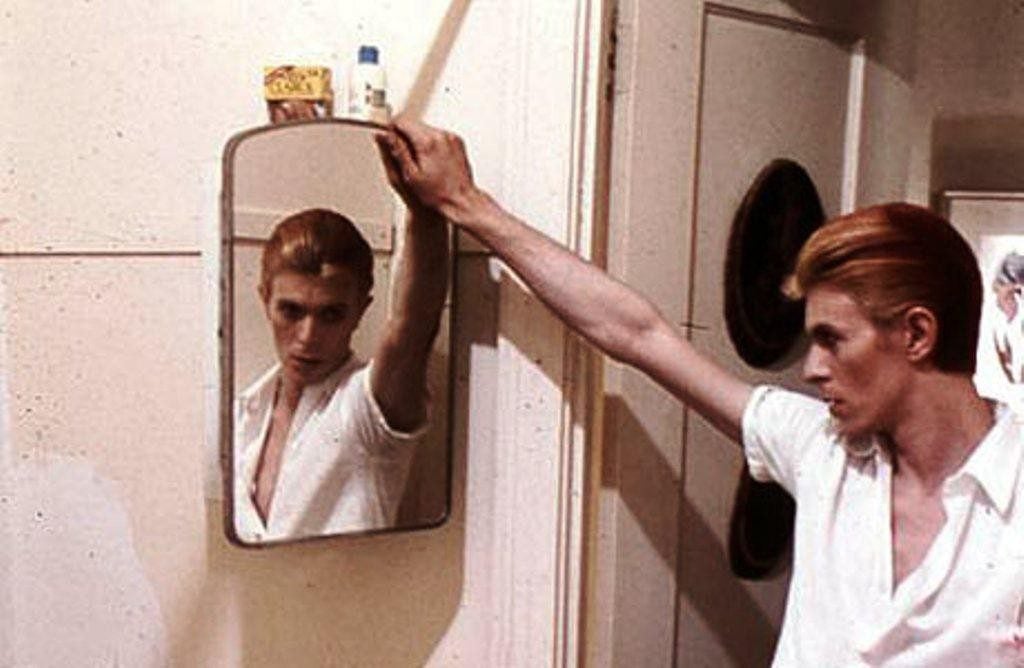

This freedom is not simply some quirk of poetry. It seems awfully close to the heart of all artistic creation. Art becomes incredible precisely when the creator experiences his creation as determining itself, during those moments we describe as “spontaneous,” whether in performance or creation. We’ve been saying this since Plato, who described poetic inspiration as a kind of possession, a lack of control over the content of the poem. “The best things we have come from madness, when it is given as a gift of the god” (Phaedrus 244a). Indeed, is this not the language we use when we speak of artistic brilliance, that the artist relinquishes control and let’s his art take over? The dancer who “loses herself,” Coltrane, who in fiery bouts of improvisation gives up a certain control over the content he produces, or the writer whose characters express a life of their own, characters who often — to the dismay of the writer — decide to “do things” the writer never conceived of — are not all of these expressions of the work of art existing in some degree of freedom, asserting, however strange it may seem, a life outside of the artist?

Indeed, this is the wish all artists seem to have for their art — that it will have a life outside of them, that it will be beautiful, great and powerful without any necessary reference to the artist who created it. To wish immortality on a work of art and to wish it freedom are one in the same, for only by being free from its creator can a work of art outlast its creator. Lady Gaga’s work will not achieve immortality because it depends entirely on the character of Lady Gaga, the death of whom will usher in the death of her work, unless she writes something good. But if the artist grants a work freedom, then it may well last forever.

Here it seems appropriate to turn back to the human person. Now for the person, like the work of art, creation and discovery are one in the same. Parents procreate their child without any certainty as to what they have wrought. That the child’s existence is contingent upon their creative action is undeniable. That their child’s identity is to some extent contingent on their parenting, their formative love, is likewise obvious. However, the child is also radically free. He surprises his parents. He is not a combination of them — he is his own world. His parents have created a mystery that moves itself, a self-determined creature, a being with a locus of freedom apart from even the strongest parenting. As such, the child appears as a synthesis of freedom and necessity, of that which is determined and that which is self-determined.

Parenting is an art, and I mean this as a fact, not as a compliment. Parenting creates the child, but it is simultaneously an act of humility towards the child, an act of formation that nevertheless recognizes the mystery of the child, the fact that the child — though utterly dependent on you for existence — is simultaneously self-determined. Children are works of art, for precisely the same reason that children are surprising. It is the joy of the parent to see his child acting in freedom, “coming into his own,” exceeding expectations — in short, as the work of art delights the artist by expressing its strange freedom, so the child delights his parent by expressing the same.

Now all I have done is point out a perceived similarity between the work of art and the human person. Whether this similarity is more than just coincidence, that is, whether I can really say “people are art” in clear truth and not just in a nice-sounding metaphor remains to be seen.