Part 2 of a series hardly worth talking about.

Sin is not religious. It is a theistic-atheistic, equal-opportunity steel-boot to the groin the entirety of humanity is doubled-over and groaning with. To be a sinner is not simply to have offended some brooding moral order which thereafter holds you in cosmic contempt. To be a sinner is to contain within yourself the reality of having done what you ought not have done. There is hardly a human alive — no matter how hip — who can coherently defend the non-existence of ethical experience, that is, the experience of our actions as things we either ought or ought not have done. It follows that no one really denies the experience of sin — the experience of that-which-we-ought-not-do — as much as everyone loves to deny that this experience could possibly mean anything so very grand as God, salvation, Heaven, Hell and all the rest. Which is fine.

But if there is such a thing as sin, there is such a thing as sinners, and to deny the existential state of being a sinner is as self-evidently ridiculous as denying the existence of my elbows, for we feel the state of sin. What we ought-not-have-done takes shape, taste and cringe-inducing color-schemes somewhere in the bowels of our interior life. It’s absurd to pretend otherwise, to pretend that we may experience doing that which we ought not do, but that this experience has no lasting effect, or rather, that it effects no change in our ontological status, our state of being. For what is the feeling of guilt but an almost bodily recognition of what ought-not-be lingering inside us? If our sins were simply to fade into the non-existent past the moment we committed them, as ethical feelings with no subsequent implications, why on earth would they continue torture us years later in the sheet-twisting hours of the night? Why are we beset by the constant possibility of being found out? Guilt is evidence of the stickiness of sin. That which we ought-not-do rips — then remains like a bullet-hole.

The idea that “the past is past,” that sins are merely “gotten over,” that they have no ultimate, lasting meaning and effect no ontological change stems from a misconception of the person’s relation to time. Personal time is not linear. The human person is not a bulldozer moving forward into the future, leaving behind him only the faded-away — shells and shadows apart from the actual life of the person. The human person summarizes his past in his present. When you meet a person, you meet a presence that is currently affected and presently informed by a past. To love a girl is to love the contents of a childhood that, in the moment of your loving her, shape who she is. When you shake my hand you shake a hand formed by my parents, a hand contingent — and contingent in the now — upon past events, past handshakes.

The past is not past in the person, but present, tangible in his every touch, audible in his words, encountered at every moment of personal encounter. Indeed it is a mark of depersonalization to subtract from people their past, to view them as having come into existence at the moment of seeing them. We do not grant to the “face in the crowd” the possible past he offers to the world — a love-life, a car crash that made him believe in angels, a singular touch by his father at the age of 9 that even now gives him courage — no, we subtract this possibility from the person and limit him to a pastless present, a animate mask devoid of content — he is a face, nothing more. He is summed up as what he looks like and what he does before my eyes — his face passes me in the crowd, and therefore he is reduced to a face in the crowd. I do not marvel at his mystery.

The past is not past in the person, but present, tangible in his every touch, audible in his words, encountered at every moment of personal encounter. Indeed it is a mark of depersonalization to subtract from people their past, to view them as having come into existence at the moment of seeing them. We do not grant to the “face in the crowd” the possible past he offers to the world — a love-life, a car crash that made him believe in angels, a singular touch by his father at the age of 9 that even now gives him courage — no, we subtract this possibility from the person and limit him to a pastless present, a animate mask devoid of content — he is a face, nothing more. He is summed up as what he looks like and what he does before my eyes — his face passes me in the crowd, and therefore he is reduced to a face in the crowd. I do not marvel at his mystery.

We rarely consider the daughterhood of the porn-star or the childhood of the convicted rapist. The subtraction of the person’s past subtracts the person, for the person exists as a “summing-up” of a past in her presence. The addition of a person’s past, on the brighter side of things, is a heroic act of re-personalization. A solider contemplates the dead face of his enemy and wonders at the fact that this entity, this abstract “bad guy” and the object of his well-honed aggression had birthday parties and a childhood filled with incomprehensible thoughts, songs and attempts to avoid cracks in the sidewalk. Here personhood is restored, the thing becomes a you, the it another-I, and all by virtue of a heroic recognition of a past summed-up in a person’s presence.

Which brings us back to the point. If being a person means containing your past, then no sins are past sins. Sin is a present, lived reality. Guilt is not a wallowing in the past, though a perverse guilt may be. Guilt is the pain of a past-filled present, or rather, the felt experience of the presence of a sinful past — of a past that isn’t past at all. If each man introduces himself as a present which sums up and is currently informed by a past, then the difference between the sinner and the sinless is that the sinner presents himself partially. The sinner contains within himself that which ought not be. He delivers a past in his present and this past contains absurdities that ought-not exist, and thus he, presently, offers to the world an incoherence.

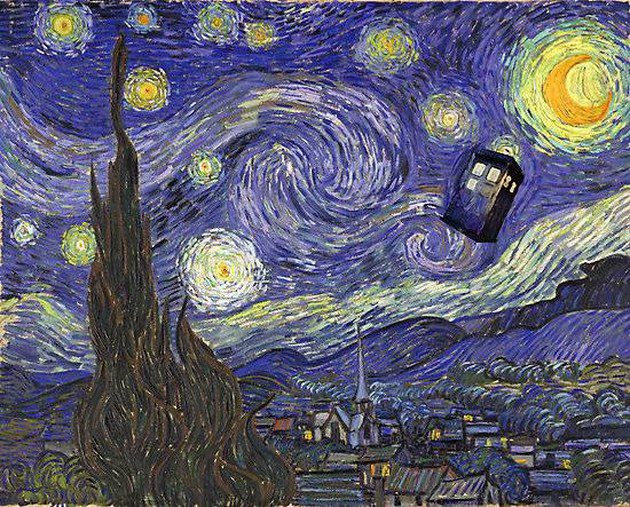

If we want to die damn good stories, to be whole, to have consistent, final meaning — then we’re going to have to be rid of sin. If being a sinner is to summarize within the present moment a past that contains that which ought-not-be, then the only possibility of becoming a story free from crappy writing — free from the irreconcilable absurdities that ought never have been part of our narrative — is to go back in time and change the past. We must, quite literally, time-travel, and having done so, alter the quality of our past, that our present might be informed coherently by that which ought be, free from that which ought not. Only then can we introduce ourselves fully, without gaps in our story.

I can only think of one method by which human person can change the quality of the past. Until tomorrow, then.