If I could offer a single corrective to our culture, a solitary word to collar-yank us safe from the semi-truck of The Intolerably Boring that daily bears on me and my generation, it would be — “describe.” (Maybe with a “dammit” thrown in for good measure. (Describe, dammit. (There we go.))) Description gives us insight, allowing us to see in, to move through the exterior life to an encounter with a person’s’ interior life. Great works of literature achieve this.

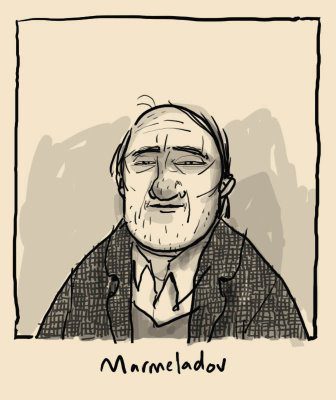

He was a man over fifty, bald and grizzled, of medium height, and stoutly built. His face, bloated from continual drinking, was of ayellow, even greenish, tinge, with swollen eyelids out of which keen reddish eyes gleamed like little chinks. But there was something very strange in him; there was a light in his eyes as though of intense feeling–perhaps there were even thought and intelligence, but at the same time there was a gleam of something like madness. He was wearing an old and hopelessly ragged black dress coat, with all its buttons missing except one, and that one he had buttoned, evidently clinging to this last trace of respectability. A crumpled shirt front, covered with spots and stains, protruded from his canvas waistcoat. Like a clerk, he wore no beard, nor moustache, but had been so long unshaven that his chin looked like a stiff greyish brush. And there was something respectable and like an official about his manner too. But he was restless; he ruffled up his hair and from time to time let his head drop into his hands dejectedly resting his ragged elbows on the stained and sticky table.

Dostoevsky does not reduce Marmeladov to a definition. He makes no attempt to give some final, total classification of what type of being Marmeladov is. The reader leaves Crime and Punishment feeling like he knows who Marmeladov is, not because Dostoevsky has summed him up, but because he has invited the reader to encounter Marmeladov.

It says something about a person, and leaves him mysterious. That which is attainable by our imagination and intellect — the “crumpled shirt” the “gleam of something like madness” — takes our hand and presses us against the unattainable, the unique subject for whom the “crumpled shirt” is but an objective expression and a revelation. Description leaves room for us to meet the person described.

It is precisely description we engage in, going about the business of offering ourselves to our neighbors, explaining our inexplicable interior lives, revealing who we are to our friends in various and hesitant bursts of vulnerability. It is the wonderful splay of bits and pieces, present in the clothes we choose, the words we speak, the songs we sing and the poetry we write. Description is in the way we glance, laugh, the particular viscosity of our handshake and the way we redden at the mention of this or that annoyance. Here, however, we are concerned with that description which seeks to give ourselves in words, to call ourselves something, to tell others — and ourselves — who we are.

In an objectified age, running scared from the person, the description gives way to the label, not in literature, but in life.

If description is an invitation to encounter the person through knowledge of their exterior life, then labeling is the attempt to reduce the person to that same exterior life. Labels pretend to offer the entire person by saying something about the person.

same exterior life. Labels pretend to offer the entire person by saying something about the person.

The word “conservative,” for instance, may be a description of an element of the person described. It is something about a particular person. As such, it may invite us to encounter the person for whom a particular “conservatism” is an objective trait. Said in another way, and the description “conservative” becomes a label. The label reduces the unique, irreducible subject to a certain type of person. The man is “a conservative,” a type we all know — certainly not an unrepeatable, unique and entirely ungraspable mystery of subjectivity. The objective has dethroned the subjective — it sits in its place with a sneer. Considered in this sense, labels are just insults waiting to be said in an appropriate tone of voice.

Any label can become an insult if accompanied by an appropriate sneer, an adequate tone of sarcasm, or a meaningful squint. This is painfully obvious in the world of political description. Spit out the word “liberal” like a pill cracked on the tongue and what was a simple description becomes a bitter barb. It has ceased to describe something about a particular person. “A liberal” has become who that person is. Say “conservative” with the appropriate pursing of the lips and narrowing of the eyelids, and what what was something about a man becomes all there is about the man. His mystery has been annulled. He is “a conservative” — and we all know what type of person that is.

Fat, gay, short, black, klutzy, slutty, insecure, communistic, stupid, retarded — insults objectify the insulted, insofar as they take something that can be said about a person and reduce the person to this particular bit of objective knowledge. Insults over-accentuate a person’s objectiveness — his observable politics, body-type, sex, sexuality, family, race, belief, mannerisms, education, culture, etc. — at the expense of his subjectiveness. Insults cauterize the possibility of moving from the exterior-objective knowledge-about to an encounter with the entire person by saying that the exterior-objective is the entire person. Insults call our neighbor a name.

For what’s in a name? Names do not give us knowledge about the person. To say a man is tall is to say something about him, but to say a man is called Daniel says nothing of the sort, for there is no objective trait signified by the word Daniel.

When two people are called “liberal,” “tall” or “talkative” we expect to find a similarity between them. When two people are called Daniel, we do not. “Liberal,” “tall,” and “talkative” refer to the objective, observable world, where traits may be classified and grouped. The first name signifies subjectivity, that this object we are referring to is someone — a person, an unrepeatable, mysterious, interior existence who thornily transcends all classification and grouping. A first name signifies the fact of the unique place the person has in the Cosmos — she is utterly unrepeatable.

We say that our first names are necessary to distinguish each from each other, and this is true, but reducing our names to products of social utilitarianism denies the empirically experienced warmth and the richness by which we know each other by name. The human person, as an unrepeatable subject, is not a type of being for whom being distinguished is merely a useful tool, in the way scientists might name the monkeys of a colony in order to distinguish between them. The human person is that type of being for whom being distinguished is a recognition of her deepest truth — that she is a unique, unrepeatable mystery, an otherness and a world unto herself. To leave a child unnamed is not an error against efficiency. It is an offense, an act of neglect and an occasion for sorrow. Because people are unrepeatable subjects, people ought to have names, and we feel this with all the force of moral obligation. The use of a first name is evidence that we are being loved, personalized, viewed and encountered precisely as a mystery of subjectivity expressed through the objective.

It is no accident that lovers in their embrace delight in repeating each other’s name, even to the fantastically direct point of asking that the other say their name out loud. The gift of the name affirms to the lover that they are being loved in their entirety, for who they are, for their entire person, right in the moment when the joys of love present the risk that they are being “loved” for something less — for the pleasure of love, for the pleasures of the body, etc. Contained in the name is the recognition of subjectivity, for the first name presents the unrepeatable subject.

It is no accident that lovers in their embrace delight in repeating each other’s name, even to the fantastically direct point of asking that the other say their name out loud. The gift of the name affirms to the lover that they are being loved in their entirety, for who they are, for their entire person, right in the moment when the joys of love present the risk that they are being “loved” for something less — for the pleasure of love, for the pleasures of the body, etc. Contained in the name is the recognition of subjectivity, for the first name presents the unrepeatable subject.

To know someone by name, in itself, is to know nothing about them. The name says nothing about the person, because a first name makes the person present to us precisely as a mystery of subjectivity, as that type of being known in encounter, not empirical knowledge.

There is incredible accuracy in our kindergarten term for insulting — name-calling. Insults and labels are offensive precisely because they propose to take the place of our names. “You’re a slut,” we say, and thereby — with cause or without — reduce the person to a particular objective characteristic, usually to some perceived sexual sin. The deepest truth about ourselves becomes our past action, not our unique, unrepeatable subjectivity.

This is the modus operandi of our culture, to run from descriptions to labels, and from labels to insults. It is a semantic expression of a spiritual problem — we prefer the neat, tidy reduction of the person to an object to the messy, messy business of loving our neighbors. I think we would profit from serious self-criticism, a serious questioning of whether the words we call people are descriptions or names, invitations-in or the willful reduction of personal interaction to the “outside,” and even moreso from a hard look at our own self-description — whether it takes on the difficulty of actual description or tends towards the immense ease of survey-responses, of “types” to live as, of conglomerations of labels masquerading as who we are.