Part 2 of a series.

Seeking to find out who-we-are from the observation of what-we-usually-do would be fine — if we were something other than persons. Gravity may be given an identity based on its typical “action,” defined as “the force that attracts a body toward the center of the earth,” but a person is that type of being with the terrifying capacity to act against who he is. He defies being defined by his usual actions because he is always free to act otherwise.

We may observe, for instance, that a particular person usually works to preserve and better his life. We may even subject him to a thousand-question questionnaire that determines with objectivity that yes, this is the case in every conceivable situation. We may then, bubbling with certainty, go about proclaiming that our observed human subject can be roughly defined as an animal who works to preserve and better his life. Having received his identity, our subject may hang himself.

It is the province of science to look at the usual, repetitive actions and characteristics of electrons, stars, muscle tissue and all the rest, and to proclaim that what is most usually observed is what a thing is. Applied to the person, the method cracks. If gravity had the remarkable propensity to, on an utterly normal Wednesday, attract a body away from the center of the earth, sending Newton’s apple careening into the atmosphere, we would tremble to define it based on its usual actions. “Gravity is the force that attracts a body toward the center of the earth, except when it isn’t” is hardly a meaningful statement. Why then do we define ourselves, who may always choose to do other than our usual actions, based on the same principle?

Let us summarize, then, the difference between a person and an object like the force of gravity. Within the force of gravity, there is no distance between what the thing does and what the thing is. The human person, on the other hand, is a being with a capacity for distance between what-he-does and who-he-is.

In my last post, we discussed the fact that the desire to extract who-I-am from personality tests — which only ever mirror what-I-usually-do — is an essentially magical desire, indulged for the simple reason that being told who-I-am by a test with the authority of science allows me to shirk the responsibility of becoming who-I-am in an immense cloud of unknowing and lifelong difficulty.

I understand the skepticism that follows. No one actually gets their identity from tests. Even if some people put too much weight on them, no one says they are an INTJ or an “extrovert” in any final, definitive way, exhausting and reducing the intricacies of their person into a word or a paragraph. Indeed, insofar as I have a tendency to exaggerate the situation in this direction, I am a second-rate satirist, dismissible in the extreme. But there is more than one way to conflate who-I-am with what-I-usually-do, and now that we understand why it is impossible to extract one from the other — for the person has the capacity for distance between the two — we have a context for what follows.

I see a willed conflation of the usually-done and identity in the invasion of the test-result into the realm of ethics, as when some one, having embarrassed a loved one, says “I’m sorry, I’m an ENFP,” or when someone else explains their ingratitude with “Gift-giving isn’t my love language,” or when we speak of being an “introvert” in defense of our rudeness, or makes some other appeal to an objective “identity type” to justify behavior.

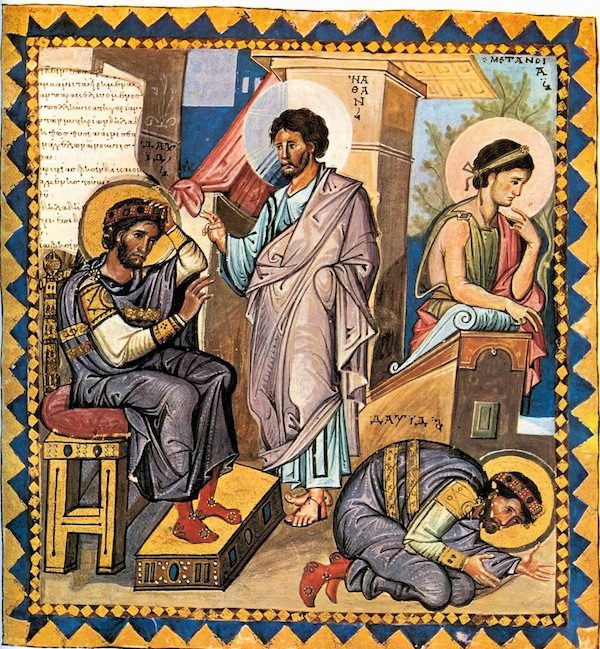

The use of the type as justification for an action is a perversion of penance.

Within the work of penance, we strive to bridge the distance between who-we-are and what-we-do by changing what-we-do. We know that, in truth, we are not assholes, so we work towards not acting like assholes. By the use of personality types, on the other hand, we strive to bridge the distance by denying any distance, claiming that what-we-do is the natural emanation of what we have been scientifically determined to be: “I’m sorry for ignoring your needs,” we say, “but you know me. I am an introvert.”

Here we have made what-we-usually-do and who-we-are one in the same, or have tended towards this conflation. We have become an immobile, scientifically-observable object. We have negated our ability to do otherwise — that capacity for absurdity which separates us from the atom and the force of gravity. We are not responsible for our actions — our actions are the unchosen emanations of our “identity.” Is gravity responsible for pushing down? Is a tree responsible for growing bark? No more would we say that an introvert — considered solely as an introvert — is responsible for turning inwards.

Only the particular person you are can be responsible, for it is only within this locus of self, wherein we may choose to do otherwise, that any motion may be properly considered as an “action,” emanating from a moment of self-determination which makes this same “self” accountable for it as its willing source. The “extrovert,” “choleric,” “leader” or “people-person” is never responsible, because he is what he usually does. His actions are not traceable to his particular person, wherein he may have chosen to do otherwise. His actions are traceable only to his type. Because his type is what it usually does — and remember, this is all personality tests can give us — his defense is a tautology: I was overemotional because I am an a type of person defined as usually doing things like becoming overemotional. I was loud and obnoxious because I am a type of person who is defined as usually doing things like being loud and obnoxious. Because personality-types are really just mirrors for what we usually do, all we mean when we say to others or ourselves that our personality-type serves as an excuse for an action is “I did A because I usually do A.”

But the problem is not personality tests. Our desire for magical, identity-bestowing personality tests is a minor result of our remarkably propensity and desire to be static objects instead of human projects. Any use of an objective type of person in the realm of ethics is the conflation of the usually-done and identity, as in: “Of course I watch porn, I’m a guy.” The word “guy” in this context is being used as the-usually-done masquerading as an identity, amounting to an godawful attempt at syllogism: “Guys” are those types of being who may be observed to usually watch porn, I am objectively a “guy,” and therefore I watch porn.

Let all such and similar suckage cease.