Rule number 6 is so incredibly true, it hurts.

1. A prostitute has sex for money. Internet-writers write about sex for money. Try your utmost to remember the difference between your writing and prostitution.

2. The Internet-writer is not paid for being read. He is paid for putting people into contact with the advertisements crowding his designated pixel-space. The more his work is viewed, the more the advertisements around his work are viewed. By increasing the sale of products he doesn’t care about, the writer generates money for people he doesn’t know, a portion of which is given back to him in thanksgiving — for being an uncaring, unknowing means to the sale of Viagra, Mormonism, and multiplayer fantasy games with mammary promise.

Considered economically, the Internet-writer is a convenient highway location on which to erect a billboard proclaiming the health benefits of light beer. Considered economically, the greatest success a blog-post can enjoy is to be left unfinished by its reader for something more interesting advertised on its sidebar. Thus the unique dialectic of the Internet-writer and the Internet-reader unveils itself — the point of the former is not to be read, and the point of the latter is to give up on reading.

3. The fundamental transfiguration the Internet effects on the craft of writing is the substitution of the reader for the viewer. A viewer need not read. A viewer may drunkenly and accidentally “land” on your writing in a desperate effort to find the News Section of The Huffington Post, glare uncomprehendingly at your banner, and rapidly engage the “back” button. You are paid for culling page-views — you will be paid for this mistake.

Internet-writing’s fundamental category of success lies not in the reading but the clicking. The latter pays, the former is merely good way of getting the latter. As such, the thumbnail — which acquires the click — has more value in determining the success of the work than the work itself — which suffers the poverty of merely being read. As such, you’ll need a tantalizing title (10 Things You Didn’t Know), a provocative image (usually breasts) desperate hyperbole (Epically AWESOME) and a subtitle guaranteeing gratification (you won’t BELIEVE #8). Think of yourself as a craftsman of thumbnails who somewhat incidentally writes articles to which the thumbnails lead.

4. Now that it has become clear that you are panting after page-views, not readers, and that it is this transfiguration that butters your bread, begin to make promises you cannot keep, vows of the “epic,” the “amazing” and the “mind-blowing,” all bolstered with guarantees that the reader will enjoy the coming-writing, and more than enjoy, veritably orgasm under the “totally shocking” information there listed. This may or may not attract readers, but it will certainly attract clicks, and it is clicks that get you paid. Remember that everyone is doing it, that CNN is a partner of BuzzFeed, that this is the very blood, mutton and modus operandi of The Huffington Post — and write at the caliber of hyperbole expected of you.

If you cannot find comfort in the zeitgeist, bearing instead medieval lurchings of guilt over the possibility that you are lying when you write a headline entitled “10 Entirely Epic Things You Never Knew About _____,” consider this parable:

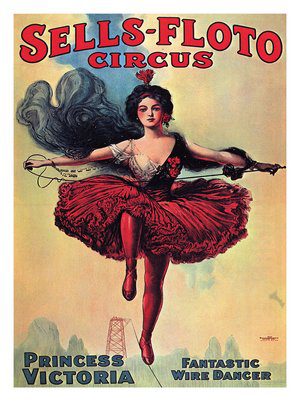

There was once a circus that set up its tent in the middle of the modern village of Fabokoce. In the days before the performance, signs were posted promising the villagers an ‘epic’ experience. When the day arrived, the conductor stepped into the ring, reiterated the promises of grandeur, and with a sweep of his hand introduced the act of the day. It was a boy spinning a ball on his finger. The boy spun his ball, the audience clapped, and the conductor thanked them for coming.

There was once a circus that set up its tent in the middle of the modern village of Fabokoce. In the days before the performance, signs were posted promising the villagers an ‘epic’ experience. When the day arrived, the conductor stepped into the ring, reiterated the promises of grandeur, and with a sweep of his hand introduced the act of the day. It was a boy spinning a ball on his finger. The boy spun his ball, the audience clapped, and the conductor thanked them for coming.

It may be reasonable to assume that the crowd left in a shuffle of disappointment, and this was very nearly the case but for one of the more modern villagers, a reasonable man in good standing with the Church, who addressed the crowd in the following manner: “If one considers the word ‘epic’ to mean ‘vaguely interesting,’ then the show was, indeed, ‘epic.'” There was much rejoicing over his wisdom. The people begged the circus to stay. The circus, seeing an opportunity to sell tickets, agreed.

So it was that, in a few years of relation between the villagers and their circus, the town developed an entirely new system of language. Words that had previously referred to specific values — really meaning “epic” or “amazing” or “outstanding”– shed their intricacies, reduced to indicating the interesting or the uninteresting. Tourists now visit the town to marvel at the unique and strangely adorable way in which the natives of Fabokoce speak of war, kittens, acts of kindness and natural disasters as equally “epic,” “awesome,” “shocking,” and “incredible.”

All of which is to say, do not feel guilty, for when the very substance of language is a lie you can hardly be held accountable for lying.

5. An Internet-writer is judged on his ability to fulfill the promise of gratification hyperbolically stated at the beginning of his work. If you find it difficult to make your writing immediately gratifying, consider that it is the same thing as making your writing immediately forgettable. As a pear on the very verge of rot smells immediately sweet, as the lively kicking of the mortally ill is only an assurance of their final stiffening, and as the immediacy of the fashion trend is a promise that it will not transcend its own fashionability, so the immediacy of pleasure promised by an Internet-article is dialectically the promise that the article is on its road to death. If your writing is good because it gratifies a drive for novelty, promising “Things You Wish You Knew About ______,” then it must become bad in the reading which renders it old, the “Things You Wish You Knew” known. No one re-reads their favorite BuzzFeed articles — they are killed in the reading, and a good Internet-writer is known by the popular corpses he leaves in his strut.

6. Recognize that your career depends on people like Miley Cyrus moving their rear-ends in ways that give you an opportunity to engage in criticism and commentary regarding the relative benefits of their gyrations. Pay dutiful homage to all such rear-ends.

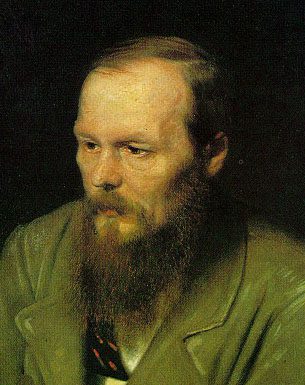

7. Given a choice between stimulating the interest of a million people or ennobling the life of one, the former pays. Write then, for the crowd. To the extent a writer wants to engage not the particular person, but the crowd, is the extent to which he must destroy the personality of his own writing. For personality in writing is an invitation to personal relation, by which the reader encounters your writing as splaying outwards from an unrepeatable first-person perspective of the Cosmos. This encounter is not to be understood in an autobiographical sense, as when the reader leaves a work knowing things about the writer. To read Dostoyevsky is to encounter the unique person which is always the source of his work, a deeper encounter than any factual information about Dostoyevsky can provide.

This is an instance of personal relation, mediated by the work, for I do not passively receive the energy of Dostoyevsky, I participate in it. I actively wrestle with the text — I dwell within its world and make decisions about what it means to me. Just as the personal relation of marriage is never the passive receiving of the other, but always a participation in the life of another, so the personal relation established between the author and the reader is not a passive, one-way street of information received, but a mingling of my life with the life of Dostoyevsky, a mingling which produces a unique relation that this universe has never seen, and will never see again.

This is an instance of personal relation, mediated by the work, for I do not passively receive the energy of Dostoyevsky, I participate in it. I actively wrestle with the text — I dwell within its world and make decisions about what it means to me. Just as the personal relation of marriage is never the passive receiving of the other, but always a participation in the life of another, so the personal relation established between the author and the reader is not a passive, one-way street of information received, but a mingling of my life with the life of Dostoyevsky, a mingling which produces a unique relation that this universe has never seen, and will never see again.

To involve your entire person in a work is to become the occasion for these unique, dissimilar personal relationships. This should be avoided at all costs, as the unique personal relation — like a friendship — is rare, and does not lend itself to bulky quantities. Thankfully, the phenomenon of a personal relation mediated through the work of writing is obscured if not altogether canceled by successful Internet-writing. There is a reason why all our articles sound the same. There is a reason why there is a mono-chromed Internet-humor that does not vary from writer to writer. There is a reason why we all write on the “trending.” The Internet-writer gathers page-views by writing in the ironic, depersonalized spirit of anonymity that characterizes the online aesthetic, as if his work was simply burped up from the bowels of the Internet itself, bearing no relation to a subjective personality.

The destruction of the personal frees the Internet-writer from the task of expressing his interior life, which frees the reader from encountering it. Instead, the task of expression is handed over to a third-party, who enters the work as a spectacle, so both the reader and the writer may sit back and say, “here is a better expression, the meaning of which we can both agree on, without every coming into relation with each other.” You might be thinking…

…but if you consider the idea of outsourcing the task of expression to a third-party, you’ll be all like…

at which point I’m all like…