One of the more exciting statistics used to denigrate religion is the fact that its followers seem to experience higher levels of guilt and shame regarding their sexual actions. Consider a headline from 2011, fairly bursting with its own conclusions: “Atheists have ‘better sex lives than followers of religion who are plagued with guilt.'” This is brilliant stuff, destined for gleeful, bi-annual repetitions by the press, for there are few things more marvelous than sexuality, and few things that so effectively trumpet the cosmic idiocy of religion than a scientific “proof” that a belief in God and his precepts screws up this selfsame marvelousness. Hence:

As a religious person quite happily “plagued with guilt,” I would like to point out a crucial misunderstanding these otherwise resplendent articles suffer from, using a recent article as my guide: “Religious People More Likely To Feel They’re Addicted To Porn, New Study Shows.” The article is being displayed by The Huffington Post, a website for children whose headlines put both the “yell” and the “low” in “yellow journalism.” The study it cites is quite correct. Religious people do tend to agree with the statements “I believe I am addicted to Internet pornography” and “I feel ashamed after viewing pornography online” at a higher rate than their godless, baby-eating peers. The interpretation of this study is where things get wibbly-wobbly. For the interpretation and, indeed, the gleeful aesthetic of this and all such publications spins itself so: Religious impulse and its doctrines manufacture shame where it doesn’t belong. Pornography is a morally neutral phenomenon — even a positive, healthy, and natural good — and it is only some trumped-up notion of sexual impurity that has us feeling awful about televised humping. This interpretation permeates the comboxes dutifully dripping from the rear-ends of all such articles. Have a summary from a Huffington Post “Super User,” a title awarded — from what I can gather — for the continuous ability to distill the vague, insinuating douchiness of particular articles into withering points:

“Watching porn is ONLY a problem if you feel obsessive guilt when watching it. If you have no problem with watching porn, then there is no problem. And what causes people to have obsessive guilt over watching porn? Religion.”

Headshot. But allow me to throw a pet monkey in the works.

Coupled with the fact that religion is apparently ruining everyone’s otherwise awesome porno experience is the fact that religion seems to be bolstering people’s committed sexual lives. From the study “The Benefit of Marriage and Religion in the United States: A Comparative Analysis,” we find that:

Cross-tabulations by religious denomination show that those with no affiliation (i.e., no involvement in religious activities) are least likely to report being extremely satisfied with sex either physically or emotionally (Laumann et al. 1994). Waite and Joyner (2001) find that emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure related to sex are higher for frequent attenders of religious services, holding other characteristics of the individual constant. Along similar lines, Greeley (1991) reports that couples who pray together say they have more “ecstasy” in their sex lives; he also finds that religious imagery and devotion is positively associated with sexual satisfaction.

Granted, this is uncertain, ideological stuff, just like the previously-mentioned, pro-atheist studies. Catholics are equally likely to delight in silly headlines — “Devout Catholics Have Better Sex, Study Says” — and frankly, I am in despair over finding an empirical answer to the question of who is having better sex. (Are we really competing? And does the winner get ice-cream?) This being said, if we are to take the available empirical data at its word, then there is a trend amongst the religious that needs explaining. Why are the same people whimpering in sexual shame over the use of pornography having great married sex?

The simple answer is that pornography is forbidden while married sex is not, so religious people feel shame about the former and joy about the latter. But this cannot explain why the religious report better married sex than their non-religious counterparts — who assumedly feel shame about neither. Nor does it make sense by our current understanding of sexuality, which doesn’t exactly render someone depressed and fearful after watching pornography into a sexual dynamo with his wife. If what our Super-Duper User said is true, and religion causes obsessive guilt over the normal, healthy sexual experience of pornography, then why would religion suddenly render him passionate over another normal, healthy experience — the experience of sex? And is this not the joke, that religious sex is either repression grotesquely unleashed…

…or a reoccurrence of the same guilt and fear that surrounds pornography and masturbation? A deeper explanation is needed to account for the apparently awesome sex lives of the religious.

Here’s one: It is for the same reason the religious feel shame over things like pornography that they are more likely to end up having wonderful sex lives. Shame enables great sex, and our inability to grasp this fact is because we have equivocated the word “shame” with “a negative, guilty feeling attached to doing some perceived evil,” when shame is actually a fascinating, positive power of the human person.

Do not allow me to idealize myself and my fellow religious. A retrospective feeling of guilt after watching pornography may be nothing more than a wallowing in a feeling of failure. If this is the case, religion operates negatively, only ever whispering “thou shalt not” into the human heart — and here we feel guilt in the same mode by which we feel awful after displeasing a parent or breaking a law. This feeling is not the same as the feeling of shame, and it certainly cannot account for the impertinent joy of the committed sexual lives of religious people. Fear engenders no joy, and great sex hardly springs from the successful side-stepping of what ought not be done. But we are deluding ourselves if we think this is a foundational experience of religion. Cringing fear and a guilt over disappointing a lawmaker is a mimicry of shame, an experience suffered when the religious degrade and reduce their own religion into a primitive ethical checklist — an experience I believe is artificially swollen in quality and quantity by the opponents of religion for easy points against a dark, guilt-laden specter.

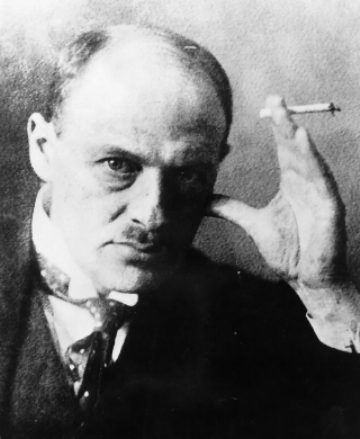

If we nevermind the bollocks, it appears that shame is a natural, positive good which — in the sexual sphere – directs the human person towards a maximum of sexual experience — towards a total experience. To understand this we must turn to the phenomenology of Max Scheler, who points out that…

If we nevermind the bollocks, it appears that shame is a natural, positive good which — in the sexual sphere – directs the human person towards a maximum of sexual experience — towards a total experience. To understand this we must turn to the phenomenology of Max Scheler, who points out that…

“…in all shame there is an act of “turning to ourselves.” This is especially clear when shame sets in all of the sudden after an intensive interest of ours in external affairs prevented our being conscious and having a feeling of our own self. A mother running to the rescue of her child who is burning in a fire does not first put on a robe. She will run…in the nude. But as soon as she has rescued her child this turn to herself, along with shame, will set in.

A very bashful woman can feel…little shame when being a model for a painter, being a patient of a physician, or when bathing in the presence of a servant…If she experiences herself in front of the painter as “given” for her aesthetic quality and as a valuable visual thing for the arts, the turn-experience will not occur. The same is the case when she is only a “case” for the physician, or the “lady” for her servant. The reasons here are the same. She does not experience herself as “individual.” [But] let us have the painter, physician or servant be for a moment distracted from their original intentions so that the woman begins to feel this happening, and the “painting,” “case,” and “lady” disappear. The woman will then strongly react with shame while “turning” to herself.

Shame directs our consciousness to ourselves, making us aware that we are what is at issue, not some image of ourselves, some limited or lesser version. This is why shame is so often misappropriated as a bad thing — the reminder of our own unique person can be uncomfortable, as when we make a mistake during a public address and turn inwards in shame, full of the painful awareness that we are not a “public speaker,” but ourselves — screw-ups, all. Scheler sums up shame as “a protective feeling of the individual and his or her value against the whole sphere of what is public and general.” In this view shame is a positive good, and the “bad feelings” associated with it are really the feelings evoked by those conditions which necessitate our blushing rush to protect our individuality — the objectifying gaze, the dirty insinuation, or the public insult.

Shame returns us to a whole view of ourselves, and this is most felt when we are wrenched from a limited view of ourselves. Shame is “a counter-reaction grown into a feeling; it is the “anxiety” of the individual over falling prey to general notoriety, and over the individual’s higher value being pulled down by lower values.” This, I would argue, is the basis for an original, natural feeling of shame in regards to pornography and masturbation, a shame shared by atheist and Christian alike.

Through pornography we are happily lost in a limited part of ourselves, in a reduction of our person to an organism pleasurably aroused by visual stimuli. There is something tragic about the pornography addict, and it is not that pornography is so awfully bad, but that real, embodied sexual love — even a technically sinful sexual love — is something so much better, something immensely more gratifying and life-affirming than masturbation to a screen. Shame is that turning inwards, away from the limited part and towards the whole of our person, in the view of which it becomes clear that we desire more than the physical gratification of a libidinous urge, and far more than the local stimulation of sexual organs. It is the sudden and often painful lurch towards a fuller life, which, in the sexual sphere, includes a desire for actual people, and beyond simply desiring another person, a desire to love and be loved by another person, to “give that person, possibly in one and the same act, the same happiness as one experiences in oneself,” and to have this bodily happiness beyond the locality of our sexual organs, beyond a detached, observed genital-feeling and towards an ecstasy of the entire body.

Shame is a vitally important power, for the indulgence of the lower tends to undo our ability to enjoy the higher. Addiction to Internet pornography makes sexual love with a real woman difficult. The prostitute, who must indulge limited relationships of utility against the urging of her shame, is not marked by a rich, deeply pleasurable erotic life, but by a growing boredom and even a disgust over sex and its contents. Shame, by urging us away from loveless acts, saves us from being “stuck” in the lower — which tends away from the near-mystical possibilities of sexual love and feeling.

But let’s stop flirting with Scheler and get to the necessary work of bisecting the adorable puppy of current sexual ethics with a meat-cleaver. Religion is not the cause of the feeling of shame over the use of pornography. One need only reflect on the first, childish experience of pornography or masturbation to see the rather obvious fact that shame exists prior to education, prior to an articulation of a particular religious doctrine concerning pornography or masturbation, prior even, to any understanding of sex — we were naturally ashamed “quite independent of an experienced reproach” in regard to libidinous indulgences. No, religion does not cause shame. It provides a framework for its growth. Our current culture, on the other hand, is about the business of repressing shame. The ideologues of modern sexuality work hard to rid us of our silly shame, thereby working against our natural drive towards the higher and the better. Religion provides a haven from modern ideology, allowing shame to be realized as a positive power within the human person.

It might seem odd that the Catholics who report being ashamed of watching pornography are the same Catholics who report “ecstasies” within married, sexual love, but this is only the case if we assume that there is no hierarchy of sexual experience. If all genital pleasures are equal, then any shame over a particular genital pleasure is a designation of an unhealthy sexuality, and all such headlines rejoicing over the fact are justified in their rejoicing. If it is the case, however, that an act of intercourse within the assurance of love, involving our emotional, spiritual and physical being, is something higher than, say, masturbation, then shame over the latter may just as well indicate the flourishing of a sexual person towards the highest possible good, the highest possible enjoyment of their sexual nature, working past the immature and incomplete indulgence of minor-league pleasure by way of a “turning inwards” that recognizes our propensity for vastly more. As Scheler puts it: “Shame is, as it were, a chrysalis; sexual love grows within it until it breaks through.”

It might seem odd that the Catholics who report being ashamed of watching pornography are the same Catholics who report “ecstasies” within married, sexual love, but this is only the case if we assume that there is no hierarchy of sexual experience. If all genital pleasures are equal, then any shame over a particular genital pleasure is a designation of an unhealthy sexuality, and all such headlines rejoicing over the fact are justified in their rejoicing. If it is the case, however, that an act of intercourse within the assurance of love, involving our emotional, spiritual and physical being, is something higher than, say, masturbation, then shame over the latter may just as well indicate the flourishing of a sexual person towards the highest possible good, the highest possible enjoyment of their sexual nature, working past the immature and incomplete indulgence of minor-league pleasure by way of a “turning inwards” that recognizes our propensity for vastly more. As Scheler puts it: “Shame is, as it were, a chrysalis; sexual love grows within it until it breaks through.”

This is the fundamental problem with headlines that proclaim atheists have better sex lives than the religious, studies that use the incident of shame following a sexual act as an objective marker for whether one’s sex life is bad. The article “Atheists have ‘better sex lives than followers of religion who are plagued with guilt,'” for instance, included masturbation, pursuing an affair, oral sex, and watching pornography as objective markers of a sex life, and used increased religious “regret” over these actions to show that an atheistic sex life, free from shame, is better. But who would really argue that a life of mediocre masturbation, shameless though it may be, offers itself as an equal to a life of passionate sex with a spouse, even if the latter may include a feeling of shame regarding, say, having an affair or watching pornography? Amidst this, one begins to sense tinges of resentment — of desperation, even — in the highly-publicized attempts to believe that a sexual life free from shame is both hotter and heavier than the sexual lives of the religious, who cultivate this concept in their mythos, their law, their liturgy and their theology.

No, shame is a wonderful power of the person, and true religion, in preserving shame, makes it possible for us to attain a total enjoyment of sexual life, even in a world waylaid by the easy, the instant, and ultimately dissatisfying. It does this by turning us inwards to regard the whole of our person, quite apart from the reductions by which we so easily view as ourselves as a sexual organ to be gratified. Shame waits for the better, and I kind of like the fact.