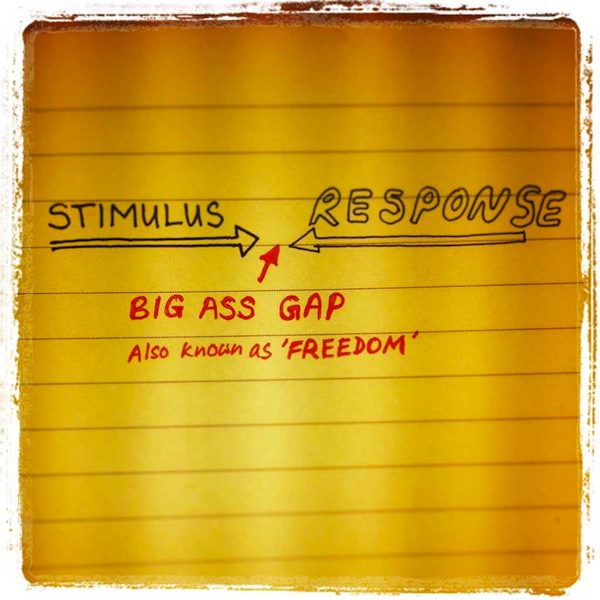

You — assuming you are a person, not a corporation or a spam-bot — are a source of action. You do not merely react to stimulus, respond to other events, or receive the motion of some prior reality into yourself and express its power out of mechanical necessity — you also do. Your actions originate in you. In this sense, you are an uncaused cause — an unmoved mover.

This is evident in the experience of responsibility. To be responsible for something is an existential acknowledgment of your own power as an authentic source of action in the Cosmos. To be responsible is to cease pretending that your actions are merely reactions, responses, and moments of being-acted upon by some prior force (say your society, your upbringing, or your situation) on which you can pin the “reason” for your action. No, in the raw and terrifying experience of responsibility, we implicitly feel that we are that locus of freedom, that keep of decision out of which which emanates Something Done.

It easy to forget this. We occupy the material world — the world of cause and effect. Within this world, all motion can be explained by some prior motion, and every so-called action can be reduced to a mere reaction. Even animal “action” may be described as a response determined by some outside stimulus. For those who have taken as their assumption that the material world is all that is — action is an illusion. The idea that we can cause something as its sole and irreducible source — when all we are is matter receiving its motion from prior motion — is ludicrous.

But the disbelief in ourselves as un-caused causes rarely stems from a dogmatic materialism (oh, were we so clever). Usually it is expressed in our vast willingness to “go with the flow.” We have a remarkable propensity to drench ourselves in the material world, to willfully become something that always receives its motion from some outside force. We may passively receive our likes and dislikes from the outside force of advertising — our buying and selling becomes the mere expression of that prior impulse. We may be entirely passive sexual beings, our sexual “actions” mere reactions to the fact of being turned on, never chosen in fullness, always done out of a feeling of being determined by stimulus. We may passively receive our ethical “convictions” from the fashions and fads of our day, claiming to care about child soldiers because of a beautifully heart-wrenching video, one that acted upon us as the true source of our conviction — a conviction which fades with the memory of the video, in a fading that reveals we never were convicted.

If I were not Catholic, I would still practice Lent, because Lent has the purely human value of reminding me that I am free. Lent is an existential meditation on my remarkable position of being thrown in to the universe as a cause. Its method is simple. Lent emphasizes our remarkable capacity to not respond to stimulus. It highlights our power to act by reminding us of our power not to act.

Lent requires fasting. Fasting can be roughly described as the decision not to eat. It is the decision to be hungry, and to remain in the state of hunger. This is an utter absurdity from the angle of every other thing in the Cosmos — everything which does not act in freedom, but by the compulsion of prior force.

Hunger acts upon us as a stimulus. Normally, we respond by eating. Indeed, within the stimulus of hunger we feel all that is material within us “crying out” for response — our stomachs growl, our mouths water, our bodies weaken, and our heads grow light. If there is no reminder that we are free, we may be lured into the easy idea that all our eating and drinking is in no way different than that of the dog snapping up the piece of meat thrown to him. We may believe, with all the ease of drifting down a river, that we are merely responding to a stimulus, that our eating is a determined reaction to our situation — not a freely-chosen, self-determined action emanating from a moment of interior decision.

Lent is a complex reminding of our own power. By fasting, we allow ourselves to feel the mighty stimulus of hunger — and ignore it. By fasting, we feel within ourselves the urge to react — and then we don’t. This denial is a powerful approval of the person, for if we can say “no” to stimulus, standing outside of the observable mechanics of nature, surely we have a unique place in the universe, a certain transcendence of the material world? Furthermore, the reminder that we can say “no” to a stimulus infuses our “yes” with freedom. Because we know that we don’t have to eat, choosing to eat is protected from ever becoming a merely determined response to stimulus — it is rather our freely chosen action.

Or consider saying no to sexual activity. The sexual act, considered materially, consist of the stimulus of sexual desire and the response of sexual activity. Because this stimulus is so powerful, our sexual lives runs the risk of living an illusion, of humming along to that song which advises we “do it like they do on the Discovery Channel,” believing that our sexual acts be reduced to merely determined responses to the fact of our being aroused — responses to stimulus and reactions to outside forces outside of our ability to do otherwise — outside of our freedom.

Or consider saying no to sexual activity. The sexual act, considered materially, consist of the stimulus of sexual desire and the response of sexual activity. Because this stimulus is so powerful, our sexual lives runs the risk of living an illusion, of humming along to that song which advises we “do it like they do on the Discovery Channel,” believing that our sexual acts be reduced to merely determined responses to the fact of our being aroused — responses to stimulus and reactions to outside forces outside of our ability to do otherwise — outside of our freedom.

It is immensely evident that our sexually free age has nothing whatsoever to do with an actual concept of freedom, simply because we have slipped from a sense of responsibility for our sexual actions. To “be responsible” is to be tied to your action as its sole originator. To “be responsible” is to feel within your gut the fantastic fact of freedom, that you are a source of real decision, and thus all your actions can be traced back to you, to a singular moment where you decided — you and no one else. If there is no responsibility, than there is no sense of our own freedom, and a sexual liberation which devalues our sense of freedom cannot be a liberation.

But by feeling sexual desire and saying no, we our reminded of our own power, and this reminding infuses each and every time we say “yes” with the joy of freedom — because we don’t have to do it, because we aren’t compelled by stimulus to respond, because we are not merely reacting to the force of sexual arousal, our sexual acts can be gifts. For it is no gift to not be able to do otherwise. If I am forced by the “laws of nature” to buy you a Ferrari, though you may enjoy the car, you could hardly call my purchase a gift. So too with the sexual act. To act out of the compulsion of the Discovery Channel is to kill the possibility of the gift, which is given in freedom.

So Lent, that strange time of year Catholics mark out with ashes on the forehead, the priestly reminder that “you are dust, and to dust you shall return,” and the giving-up of precisely the things we most want to do — smoking, drinking, eating meat, and cursing under our breath being popular options — this season is possibly the most preeminently human practice alive in the world today. It is an education in freedom.