Young Earth Creationism (YEC) is, ironically, relatively young. I’ve written about its origins at Religion&Politics (start in paragraph 4), with a follow-up at Times&Seasons. A recent article in Scientific American highlights the arrival of Young Earth Creationism in Europe.

Young Earth Creationism (YEC) is, ironically, relatively young. I’ve written about its origins at Religion&Politics (start in paragraph 4), with a follow-up at Times&Seasons. A recent article in Scientific American highlights the arrival of Young Earth Creationism in Europe.

I take issue with one paragraph.

We have learned that confronting creationism is not a scientific matter but rather a political one. To engage creationism it does not suffice to line up all the evidence and arguments in support of evolutionary theory. Instead, scientists have to get out and operate on all platforms where creationists are active. This includes giving public lectures, writing op–eds and articles in popular magazines, weeklies and newspapers as well as discussing the issue in television and radio broadcasts, developing and maintaining Web sites on evolution, and via exhibitions.

I agree that we need scientists and educators to write more for the general public, to translate technical understandings for laypeople about specific issues, but also about the widely misunderstood nature of science, e.g. here (a BYUS article) and here. I also agree that “confronting creationism is not a scientific matter,” but the solution is not better or more science. You can’t convince a Young Earth Creationist of their incorrectness simply by throwing more science at them, because scientific arguments are not the cause of their Young Earth Creationism, but an effect of it. At its root, the scientific aspects of YEC are entirely secondary to and dependent on the interpretation of the early chapters of Genesis.

This is why the Ken Ham/Bill Nye debate was absolutely pointless. They weren’t actually debating the same topic, really. Bill Nye’s science is powerless against YEC; not because he’s wrong (although he certainly has been, at one time making “the entire US philosophy community collectively choke on its morning espresso” and here), but because he can only talk science. And that’s not convincing YECs, who already know that YEC views of science aren’t mainstream.

What, then, changes YEC minds?

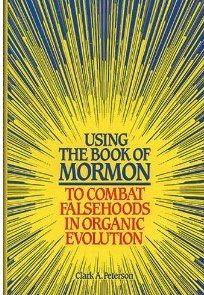

I’ll tell you what, and use myself as an example. I read a lot of books on my mission (my stories here and here.) I mistakenly traded a good Nibley volume for something called Using the Book of Mormon to Counter Falsehoods in Organic Evolution. It poked a few scientific holes in evolution and then drew heavily on Joseph Fielding Smith and others to make an argument from authority. In spite of being a doctor’s kid and a science nerd in high school, I wasn’t terribly well versed in philosophy of science or biology. I didn’t embrace YEC, but I did become quite skeptical of evolution. Fast forward two years.

My fiancé was a major in Molecular Biology with a Chemistry emphasis, and the only thing we had an argument about was evolution. Her science didn’t really change my mind, but I could tell that I’d been a little misled. She still couldn’t explain what Genesis meant, couldn’t replace the simplistic power of a context-free reading nor explain Joseph Fielding Smith. (No one seemed to know about President McKay.)

We got married anyway. Happy day.

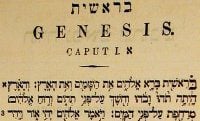

As I finished my ancient Near Eastern Studies undergrad, and went on to graduate studies in Semitics, I realized that I had been reading Genesis through modern, western eyes. Misreading, actually. Now, having done more science, lots of modern and ancient Near Eastern history, and reading Genesis in context, I understand why Joseph Fielding Smith interpreted Genesis as he did, why he was wrong, and also why being wrong here doesn’t really undermine his apostolic authority for me.

That’s my story, but it plays out the same way with others. Here are two Evangelicals with advanced degrees who used to be YEC preachers but changed their story.

“At the same time that I was beginning to have scientific questions about the legitimacy of the young earth position, I was also beginning to delve seriously into the language and setting of the Genesis account itself, and that was the most eye-opening of all. I realized that all my life I had been reading Genesis from the perspective of a modern person. I had read it through the lens of a historically sophisticated, scientifically influenced individual. I assumed that Genesis was written to answer the questions of origins that people are asking today.But I had never asked the most vital question of all: What did Moses mean when he wrote this text? After all, “my Bible” was Moses’ “Bible” first. Was Moses acquainted with Charles Darwin? Or Henry Morris? Or Hugh Ross? Was he writing to discredit any modern theory of evolution? Were his readers troubled by calculations of the speed of light and the distance of the galaxies from earth? Were they puzzling over the significance of DNA? Were they debating a young earth versus an old earth? Would they have had any inkling about a modern scientific worldview? If you agree that the answer to these questions is obviously no, then the logical question is, what was on their minds? How would they have understood Genesis 1? I have read a great deal of literature debating the meaning of Genesis 1, but rarely do the authors even ask, much less start with, the question that is the most important question of all: What did Genesis mean to the original author and original readers?”- Johnny V. Miller and John M. Soden, In the Beginning … We Misunderstood: Interpreting Genesis 1 in Its Original Context, 21. My emphasis.

Science didn’t convince them YEC was wrong; it was having an open mind, asking questions, and especially getting at the ancient Near Eastern setting of Genesis. Heck, they’re still really conservative Evangelicals, believing that Moses wrote Genesis, under the influence of Egyptian cosmology. (I disagree, but still found their book worth reading.)

The point is, a demonstration that the modern YEC interpretation doesn’t make sense of the text and its cosmology nearly as well as an ancient interpretation, which most people don’t even know (see here to learn), has far more convincing power than more scientific explanations. For a similar example in an LDS context, see this post by Julie on the Flood. (My quick take on the flood here.)

Biologos has some great essays, and now they have a book collecting stories of when and how Christians became convinced that scripture wasn’t against evolution. How I Changed my Mind About Evolution: Evangelicals Reflect on Faith and Science includes essays by NT Wright, Francis Collins (MD/PhD, director of the National Institute of Health and head of the Human Genome Project), and others less well-known to LDS. I haven’t read it yet, but I imagine their stories follow the pattern above.

Confronting creationism, then, is not a scientific matter (although it’s important) nor a political one (although education can help), but an interpretive matter. One’s understanding of Scripture in the abstract, and Genesis in particular, is the tail that wags the scientific dog for YECs.

As always, you can help me pay my tuition here, or you can support my work through making your regular Amazon purchases through this Amazon link. You can also get updates by email whenever a post goes up (subscription box on the right). If you friend me on Facebook, please drop me a note telling me you’re a reader. I tend not to accept friend requests from people I’m not acquainted with.