The only ancient description we have of the making of papyrus is that of Pliny the Elder in his Natural History Book XIII. He wrote in the latter half of the first century A.D., and while some scholars have questioned whether he had actually seen the process due to some of his remarks, even if he got it second hand, this is valuable first century information…

Pliny, Natural History, 13.74-82

Paper is made from the papyrus plant by separating it with a needle point into very thin strips as broad as possible. The choice quality comes from the center, and thence in the order of slicing. The (choice) quality in former times called ‘hieratic’ because it was devoted only to religious books has, out of flattery, taken on the name of Augustus, and the next quality that of Livia, after his wife, so that the ‘hieratic’ has dropped to third rank.

The next had been named ‘amphitheatric’ from its place of manufacture. At Rome Fannius’ clever workshop took it up and refined it by careful processing, thus making a first-class paper out of a common one and renaming it after him; the paper not so reworked remained in its original grade as ‘amphitheatic’.

Next is the ‘Saitic’, so called after the town where it is most abundant, made from inferior scraps, and from still nearer the rind the ‘Taeneotic’, named after a nearby place (this is sold, in fact, by weight not by quality). The ’emporitic’, being useless for writing, provides envelopes for papers and wrappings for merchants. After this there is (only) the papyrus stalk, and its outermost husk is similar to a rush and useless even for rope except in moisture.

Paper of whatever grade is fabricated on a board moistened with water from the Nile: the muddy liquid serves as the bonding force. First there is spread flat on the board a layer consisting of strips of papyrus running vertically, as long as possible, with their ends squared off. After that a cross layer completes the construction. Then it is pressed in presses, and the sheets thus formed are dried in the sun and joined one to another, (working) in declining order of excellence down to the poorest. There are never more than twenty sheets in a roll.

There is great variation in their breadth, the best thirteen digits, the ‘hieratic’ two less, the ‘Fannian’ measures ten, the ‘amphitheatic’ one less, the ‘Saitic’ a few less–indeed not wide enough for the use of a mallet–and the narrow ’emporitic’ does not exceed six digits. Beyond that, the qualities esteemed in paper are fineness, firmness, whiteness, and smoothness.

The Emperor Claudius changed the order of preference. The excess fineness of the ‘Augustan’ paper was insufficient to withstand the pressure of the pen; in addition, as it let the ink through there was always the fear of a blot from the back, and in other respects it was unattractive in appearance because excessively translucid. Consequently the vertical (under) layer was made of second-grade material and the horizontal layer of first-grade. He also increased its width to measure a foot.

There was also the ‘macrocolum’, a cubit wide, but experience revealed the defect that when one strip tears off it damages several columns of writing. For these reasons the ‘Claudian’ paper is preferred to all others; the ‘Augustan’ retains its importance for correspondence, and the ‘Livian’, which never had any first-grade elements but was all second-grade, retains its same place.

Rough spots are rubbed smooth with ivory or shell, but then the writing is apt to become scaly: the polished paper is shinier and less absorptive. Writing is also impeded if (in manufacture) the liquid was negligently applied in the first place; this fault is detected with the mallet, or even by odour if the application was too careless. Spots, too, are easily detected by the eye, but a strip inserted between two others, though bibulous from the sponginess of (such) papyrus, can scarcely be detected except when the writing runs–there is so much trickery in the business! The result is the additional labour of reprocessing.

Common paste made from finest flour is dissolved in boiling water with the merest sprinkle of vinegar, for carpenter’s glue and gum are too brittle. A more painstaking process percolates boiling water through the crumb of leavened bread; by this method the substance of the intervening paste is so minimal that even the suppleness of linen is surpassed. Whatever paste is used ought to be no more or less than a day old. Afterwards it is flattened with the mallet and lightly washed with paste, and the resulting wrinkles are again removed and smoothed out with the mallet.

Here below of course is the plant itself.

This is a very young plant, not a mature one. They can become much larger and the stalk, which is triangular and supplies the materials for the papyrus, much thicker. For example, here is an old papyrus stalk from the Vienna museum…

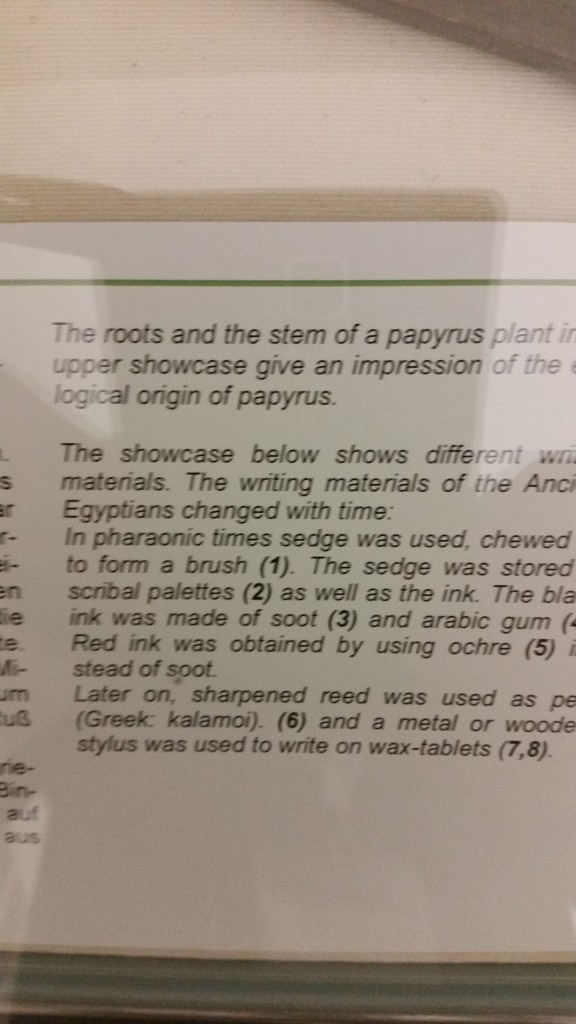

A stylus was the instrument used to write on papyrus, and here are some samples from the Vienna museum.

Soot was the main ingredient in the ink, soot and water.

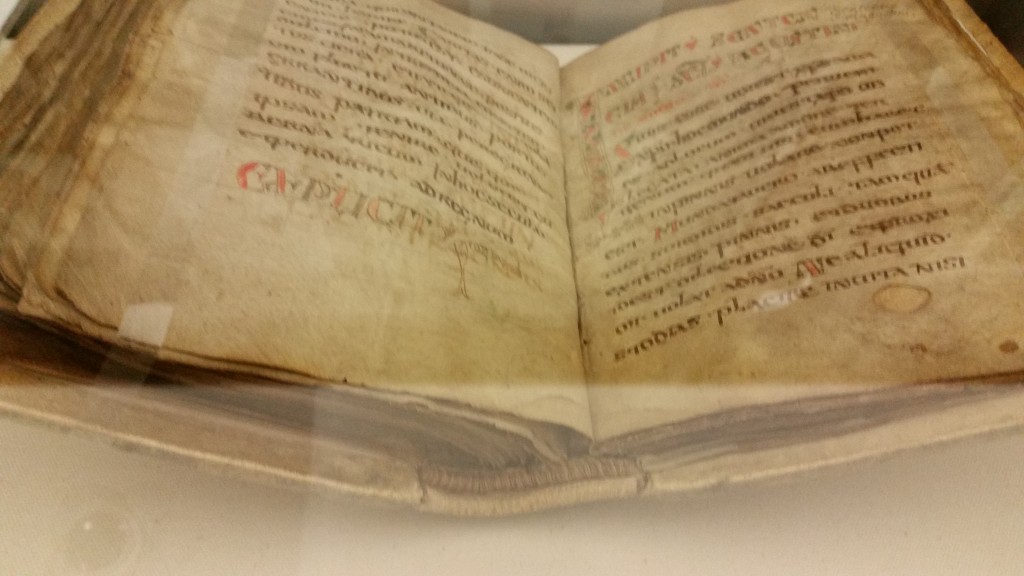

Papyrus was indeed used up to the 10th century A.D., but it was gradually replaced by the much more durable parchment made of the hides of goats. In terms of form, the papyrus roll was replaced by the codex, and here is an early one of an apocryphal Christian book, The Gospel of Barnabas…

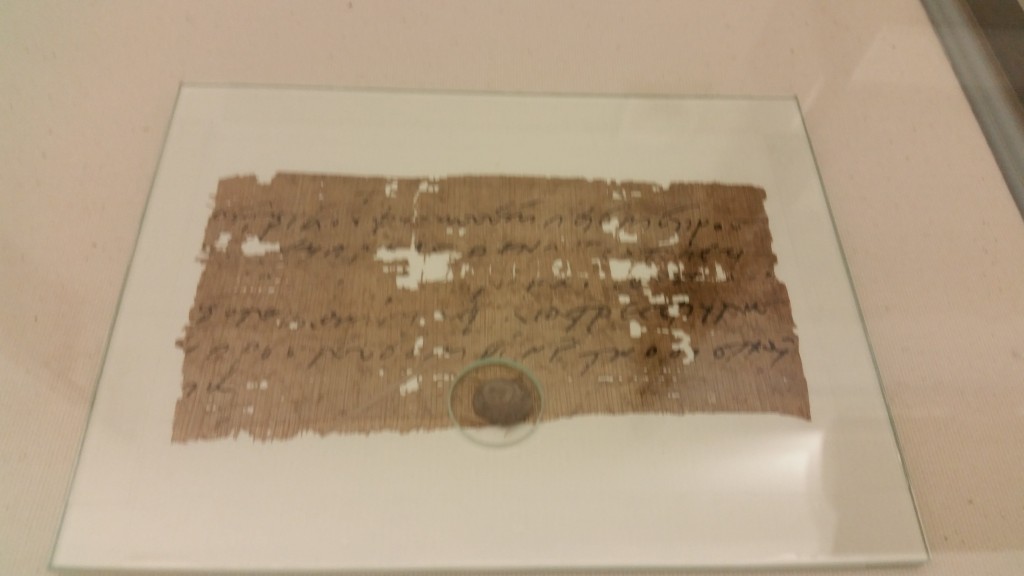

Official documents often would have seals, particularly papyrus rolls, something clearly referred to in Revelation 5-6. Here is a single example of a document seal.

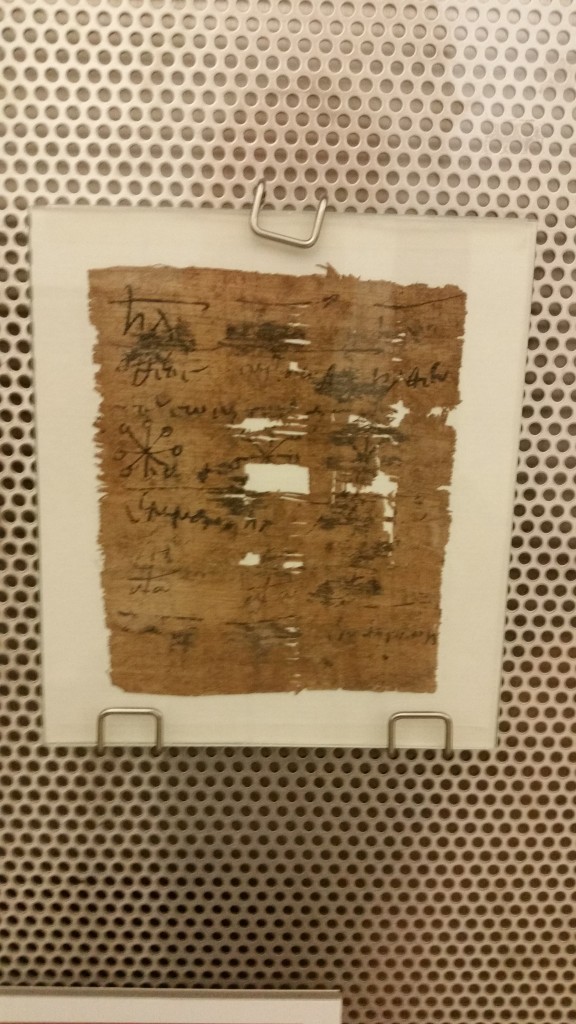

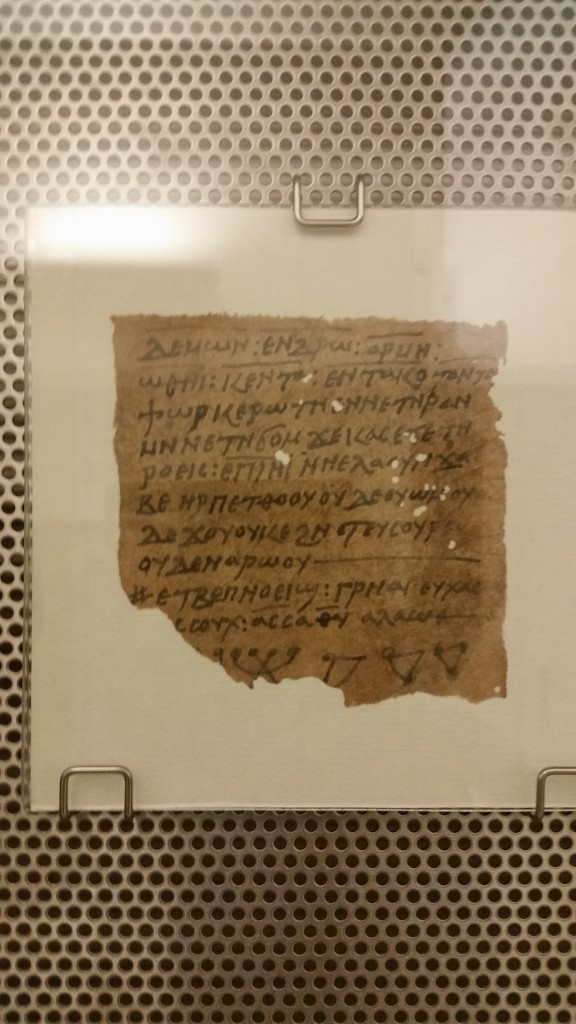

The Vienna museum has all sorts of extra-Biblical papyri, including early samples, on the Jewish side of things, from Philo, the Wisdom of Solomon, the Mishnah, and Sirach, and from Xenephon, Vergil, Cicero, and other Greek orators on the Greco-Roman side of things. There are also some magical papyri as well, and some doodling including a small example of the sator/rotas square (look it up on Wiki).

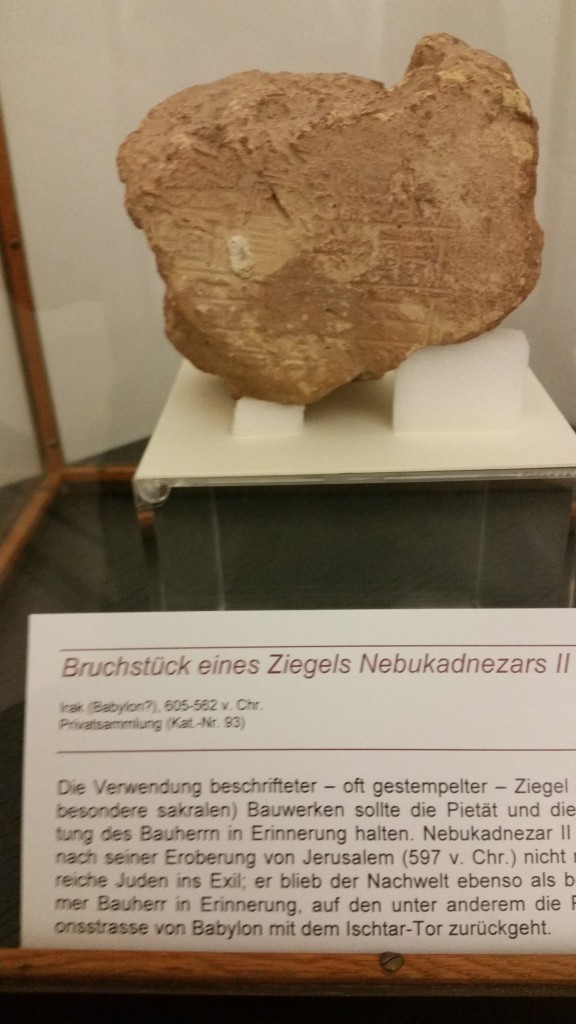

Lastly the oldest piece in the museum is an inscription on a rock from Nebuchadnezzar…