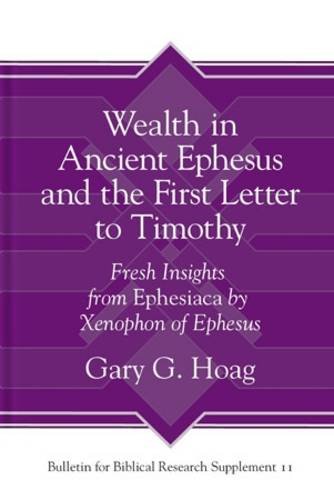

Q1.BEN: First of all thank you Gary for this stimulating new book of yours based on your study of the little known work by Xenophon of Ephesus, his ‘Ephesiaca’. It is always a good thing when we do primary source research on extant documents from the same era and social location as the NT documents. What was it that got you interested in studying this particular possibly first century A.D. romance novella in tandem with 1 Timothy?

A1.GARY: After my first year of PhD research at Trinity College, Bristol University, I prepared a survey of literature for my advisor, Philip Towner, and reported that debate on texts with wealth in view in 1 Tim swirled around the function and meaning of rare language. Towner instructed me to schedule a visit with Abraham Malherbe at Yale to ask how he unlocked the medical imagery in the PE to gain insight for approaching the texts on handling riches in 1 Tim. Later in 2007, Malherbe spent an afternoon with me and 1 Tim and advised pointedly, “Don’t search ancient material with an Ephesus provenance, read it. Few people read the primary sources! There you will find what you are looking for.” This counsel charted my course.

I started with inscriptions and spent almost a year in Die Inschriften von Ephesos. Then I turned to numismatic evidence exploring The Coinage of Ephesus and other related sources. When I turned to literary documents later in 2008, I came upon Ephesiaca in English while reading Collected Ancient Greek Novels by B.P. Reardon and then located the Greek text on TLG. I discovered that Xenophon of Ephesus used many of the rare terms and themes that appear in 1 Tim and brought to life the world of the wealthy in Ephesus.

Here’s where it got interesting. I found that Ephesiaca had likely been overlooked by biblical scholars because since about 1726 when the lone copy of the manuscript came into view it had been broadly labeled by classical researchers as a “romance novel” and dated to the second or third century CE. More recently, classical scholars like Reinhold Merkelbach (1962) and R.E. Witt (1997) have contended that Ephesiaca be codified not as a romance novel but as a hieros logos, “a sacred writing,” based on its composition and didactic intent.

Meanwhile, another classical scholar, James O’Sullivan (1995) argued convincingly for an earlier mid-first century date (c. 50 CE) based on clues within the manuscript. The year after I came upon the story (2009), it was published in the Loeb Classical Library under the title Anthia and Habrocomes. In his introduction in the LCL, Jeffrey Henderson appeared to concur with the possibility of the earlier dating. All these factors came together and ignited my enthusiasm.

By this time, I realized that I had come upon an ancient document that depicts details about life and society for the wealthy Ephesus not found elsewhere that classical scholars had dated to broadly the same timeframe as Luke’s Acts of the Apostles places the ministry of the Apostle Paul in Ephesus (c. 52-54 CE). Consequently, I determined to consider how Ephesiaca alongside other ancient evidence might enhance our understanding of social and cultural context of the the teachings on handling wealth in text of 1 Tim.

That’s the story. Ironically, your first question was the same one that Larry Kreitzer and David Wenham asked me in my final viva. With them, I am glad you found my research stimulating!