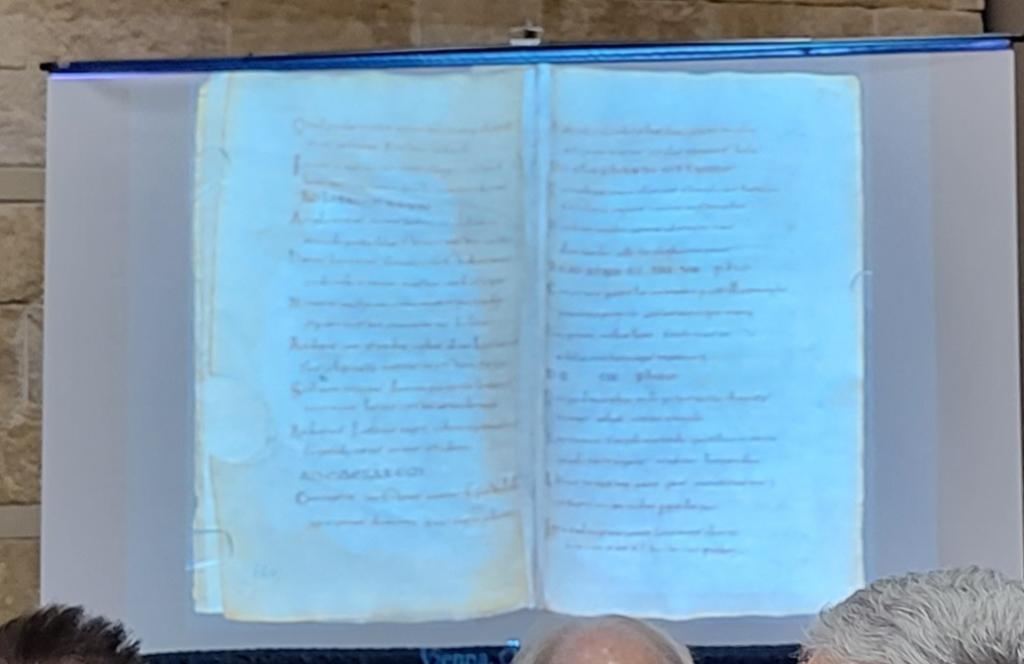

There was a lecture at the SBL in November in Denver about the beginnings of the use of codexes, and this particular lecture traced it back to the handling of Martial’s writings, most famously known for his Epigrams in the first century. Here are some slides about it from the lecture….

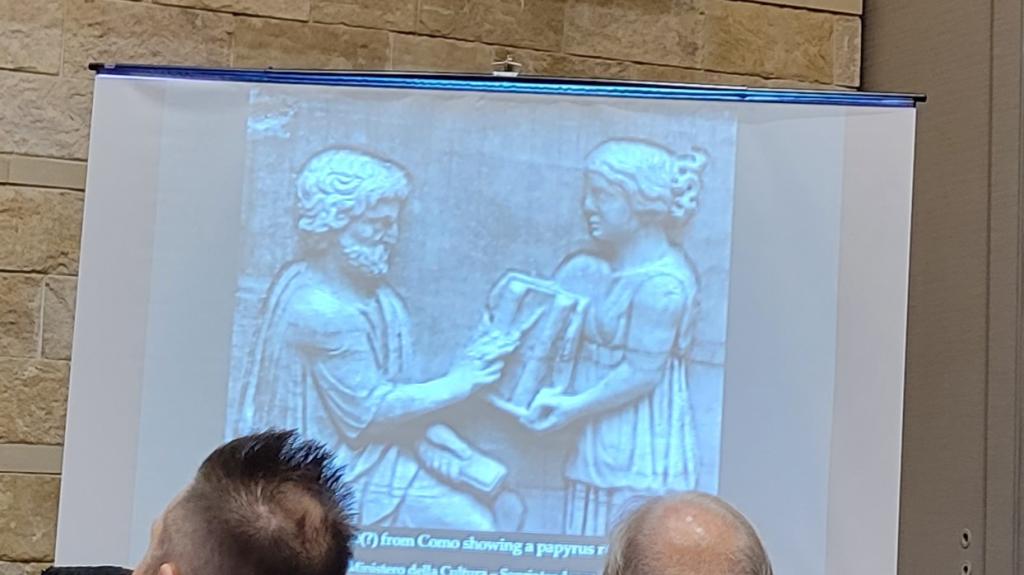

Brent Nongbri was the presenter of this lecture and the title involves imagining, because we don’t actually have a Martial codex, but as Nongbri points out we have early references to it, and in addition plenty of evidence about the addition of the use of parchments/membrana in addition to papyri. The evidence as we have it suggests Christians weren’t the first to use codexes but they were early adapters apparently. So let’s consider the beginnings of the early ‘book culture’ as it came to be called.

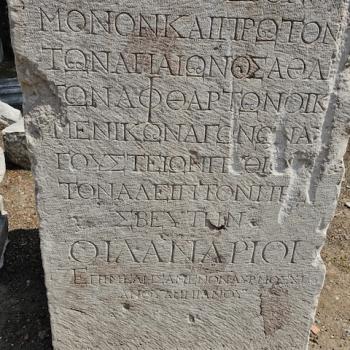

E.J. Kenney rightly reminds us (in Vol.1 on The Early Republic, p.3) that “the literary life of Greece and Rome retained the characteristics of an oral culture, a fact reflected in much of the literature that has come down to us. The modern reader, who is accustomed to taking in literature through the eye rather than through the ear, cannot be too frequently reminded that nearly all the books discussed in this history [of the classics] were written to be listened to.” If we go back to the 2nd century B.C. Kenney stresses the “literary dependence on Greek models was part of a general (if not universal and unquestioning) acceptance of contemporary Greek culture by the Romans of the second century B.C.” (p. 5). And this most certainly applies to the adopting and adapting of Greek rhetoric, such that when one gets to Quintilian at the end of the first century, he is rightly called just an epitomizer or compiler of the insights of the earlier Greek (and Latin) rhetorical treatises. The Romans were ‘almost overnight’ the inheritors “of a copious and highly developed body of critical,grammatical, and rhetorical theory and practice.” Down to the time of Augustus, Roman education essentially was Greek…it was Greek poetry and Greek oratory that formed the staple of study and imitation.” (p. 5). In Cicero’s own day, his speeches were seen as exemplary and used for teaching, because there was little else in Latin of that quality of rhetoric. Kenney avers that it was Cicero’s treatises–De oratore, Orator, and Brutus that laid the foundation for the beginnings of Latin eloquence. But it is well to remember who Cicero’s teachers were— Greek rhetoricians, including his training in Asiatic rhetoric. Elite Romans were used to hiring, or buying Greek philosophers and rhetoricians to train their children. The ultimate aim of all such training was “to produce the perfectus orator– a man trained in the art of effective speech in prose.” (p. 7).While Quintilian gives lip service to the idea that the well educated person should know some philosophy, natural science, history, and law, the ultimate use and aim of such study was not to know those subjects as independent schools of thought, but to know them so as to provide illustrations and examples to use in speeches!

Kenney is right to remind us that the real rise of training in rhetoric in Latin coincided with the decline of real political liberty and the rise of Octavian and the birth of a dictatorial approach to government like other previous Empires. This of course changed the character of what was rhetorically wise and possible. Since real debate and real voting was being squashed rhetoric had to focus on lawsuits (judicial rhetoric) or funeral oratory (epideictic), but there is an exception to this rule. In the context of the Christian movement the dominant rhetoric was deliberative rhetoric, seeking to persuade people about the Gospel, and let them freely embrace it. There was plenty of room for encomiums as well, but Christians were urged to avoid the law courts where judicial rhetoric and logic chopping reigned supreme. Christians were to settle their own differences in house (see e.g. 1 Cor. 5-6). A further partial exception is the rise of more and more public declamation in the agora or forum where rhetors would provide suasoria, in which the speaker advises an historical or fictional figure on what they ought to do (with implications for real living persons to be deduced by the audience) or controversia in which mock legal debates between two advocates are staged. “To this end, they employed all possible resources: vivid description [ekphrasis], striking turns of phrase, paradox,…sententious epigram, and emotional extravagances of the most extreme kind.” (p. 8). Roman education was still patterned on Greek education until the 5th century A.D., only with even more emphasis on rhetoric.

As Kenney goes on to make clear, the triumph of the codex over the roll, and parchment over papyrus coincides with the triumph of Christianity in the Empire by the 4th century A.D. and thereafter. (pp. 26-27). There are a variety of reasons for this, not least the evangelistic nature of Christianity and perhaps especially its reverence for its sacred texts. But there was a practice side to this— parchment, ink, scribes, in short book production was expensive, and because Christianity like Judaism was a religion dependent on sacred texts, the sooner the texts could be put into a durable form that was not easily destroyed or subject to decay, mold, and the like. I doubt it is an accident that it was also in the 4th century that the church east, west, and in Africa agreed that a certain 27 books constituted ‘the New Testament’ and that it needed to be preserved in codex and parchment or even vellum form. It may even have been at the Council of Nicea in 325 that Constantine first commissioned the production of high quality Christian Scriptures, and one can speculate whether we are looking at one of the original such collections in Codex Vaticanus or Codex Sinaiticus etc. Finally, it is also important to note that this book culture, did not leave the oral and rhetorical culture behind. The texts of Scripture were continually read out loud in Christian meetings, partly because the literacy rate was low, and partly because Christian preaching was simply a continuation of the art of persuasion—- rhetoric.