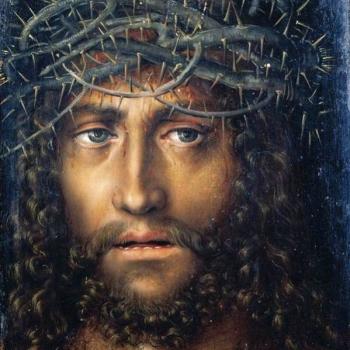

Saint Patrick of Ireland, by Aidan Hart. I am away this week, and have not had the time to put together a Sunday Pilgrimage entry for you. Apologies: I promise that we will return to our wanderings through Christian England next week. Instead, since tomorrow is St Patrick’s Day, here is an article I wrote here three years ago, about Ireland’s patron saint and his continuing presence in this land. Some of you may appreciate reading it again – and new readers, for the first time. Today is St Patrick’s Day. It’s a national holiday here in Ireland, during which there is a lot of drinking and parading and the wearing of green leprechaun hats. I’m too old for that sort of thing, and the leprechaun hats don’t suit me anyway. Instead, this morning I was in church listening to two Irish friends singing an old hymn about the saint they learned at school, in harmony with a Romanian nun. It’s an experience I recommend. This evening, I’ve been sitting by the fire reading about St Patrick. Now I want to write something impulsive about the saint. I think he has something still to say to us. I’m not Irish, I know: but then, neither was he. In fact, Patrick – Patricius to his friends – was British like me, and like me he grew up in a time of imperial decline, though he had no idea how quickly the empire of which he was a subject would collapse, and all its assumptions drain away. Patricius was a British subject of imperial Rome, born around the year 400 into a middle class family, and trained for comfort and success. All of that went out of the window when, at the age of sixteen, he was kidnapped by Irish slave traders and sold to a petty king named Miliucc, who sent him out to the hills to work as a lone shepherd. Frightened, lonely and confused, a child in an alien land with no help, family or friends, Patrick did what a lot of people do under similar circumstances: despite being a self-declared atheist, he started praying. The most entrancing and readable account of Patrick’s life I’ve come across is in Thomas Cahill’s excellent book How The Irish Saved Civilisation. Here he explains the end result of Patrick’s time alone in the hills, with only sheep and God for company:

Patrick did indeed get back to his family in Britain, but nothing was the same. He had met God, and they didn’t understand him any more. Patrick took himself to Gaul for a theological education, and after being made a Bishop, he was sent to spread the Christian message to the pagan kings of Ireland, as the first Christian missionary since St Paul, 400 years before. Patrick’s time in Ireland, in Cahill’s telling, was transformative, and not just for this country. He converted the warring tribal kings to the Christian faith, and thousands of their people too, and he did it not with force (one former slave versus a nation of battle-hardened warrior kings would not have been a fair contest) but with love. ‘His love for his adopted people shines through his writings’, writes Cahill. Indeed, Patrick, after a while, went native. When he travelled back to Britain later in life to plead for some of his converts who had been taken in slavery by British pirates, his former countrymen no longer trusted him as one of their own. Patrick’s greatest achievement in Ireland, in his lifetime at least, may have been the abolition of slavery, a cause about which he was understandably passionate, and for which he made a radical Christian case. Cahill calls him ‘the first human being in the history of the world to speak out unequivocally against slavery’:

During his lifetime, Patrick was unknown outside Ireland. He lived around the time of St Augustine, the great influencer of the Christian West, but his understanding of his faith, suggests Cahill, was quite different:

What made Patrick this way? Ireland. There is something special, something unique, about Irish spirituality, and especially about the early centuries of the Christian faith here. During the first five centuries of Irish Christianity, over 200 saints emerged from this tiny island. For comparison, the next ten centuries produced just three. The shape that Christianity took in Ireland is not the same shape it took amongst civilised Roman Christians like Augustine. It was not the shape of which Popes approved. It was wilder in some strange way: embedded in the land and emerging from it in a shape that was in no way a betrayal of its teachings, but was in no way either a mirror of the civilised, imperial centre. Irish Christianity today – despite its centuries of centralisation by a Rome that still behaves like an empire, despite its great diminishment, despite its scandals and collapses – despite all of this, away from the centre, out in the mountains and the fields, it still lives. I feel it every time I go out. Anyone can. It lives on Croagh Patrick, Ireland’s holy mountain, up which people still walk barefoot every year on the same day: It lives in the wells in remote fields, and in the ruined chapels and blasted skelligs, and on the holy islands with broken towers, abandoned for centuries by people but perhaps not by the Spirit: It lives in the the caves that saints once slept in, around which some power still hovers: It lives in the land. It is waiting for something. I don’t know what. But it is patient. It is patient like Patricius was. He left us an island whose monks, as Cahill demonstrates, took into themselves, copied and kept alive all of classical and Christian learning in the face of barbarian fires. He left us a leafy, wet, strange and magical Christianity, entwined with the spirit of this Atlantic island. And he left us a hymn, a song which to me speaks of the mystic, green spirit of true Irish – and British – Christianity still. St Patrick’s Breastplate, they call it; or sometimes The Deer’s Cry. It is a prayer, an incantation, a chant, a spell. Sixteen centuries later – well, it is still quite something. Try speaking it aloud to yourself, and then see what power swirls around you.

Special thanks to Mr. Kingsnorth for this excellent post. I, like St. Patrick, am an Englishman who loves Ireland. |